“Yo No Soy Guapo”: A Film that Makes You Dance

Sonidero culture is particularly strong in Mexico City, where the amount of active practitioners, supporters and loyal followers is truly surprising. This has inspired scholars, photographers (see this previous blog) as well as independent film makers who have documented this incredibly lively SST scene. Among them, filmmaker Joyce Garcia, whose film Yo No Soy Guapo was part of the screening program of Sound System Outernational #7, held online in July 2021. We are excited to have on the SST blog longstanding friends and collaborators Leonardo Vidigal from Brazil and Australia-based Moses Iten who have reached out to Joyce Garcia to learn more about her inspiring movie.

by Leo Vidigal and Moses Iten

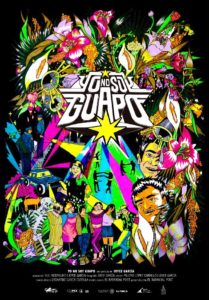

Film poster

“The film is an explicit invitation to dance—to be in an actual dance in the public space—because the presence of the sound system has the great power to hit the body, to make you dance, meet people and socialize.” Mexican filmmaker Joyce Garcia describes her film ‘Yo No Soy Guapo’ in this way. The movie is a vibrant documentary on Mexico City’s sonideros and the people who built the culture bringing cumbia and salsa to the streets of the ancient Aztec capital.

Australia-based cumbia DJ/producer and researcher Moses Iten created a transcontinental bridge for us to participate in this online interview with Garcia about her film. Garcia began telling us abouther first contact with sonidero culture.

“I’m not from Mexico City. I’m from the eastern part of the country, from Veracruz, which is on the East Coast, on the Gulf of Mexico. We also have a dance culture that is very, very rooted and present like the danzón, son montuno, salsa, and the whole Caribbean culture is very important in my city. When I arrived in Mexico City I started to look for work, to make my dreams come true. I went to a dance. I have many friends from this city who were born here, their culture is sonidero culture. They took me to sonidero dances, which for me was a bit like, “Wow!” Like home, you know? Like my home, my house, a place that I identify with, where I felt welcomed and embraced. Because I believe it is a very powerful space of freedom, even anarchist, if we want to call it that. Something that doesn’t need an industry and doesn’t need any capitalist thing. Because it is totally contrary to them. It’s the need for catharsis, the need to coexist, the need to identify with others and building a community.”

The film title refers to a famous salsa song of the same name recorded by the legendary Cuban group La Sonora Matancera, which is part of the repertoire of many sonideros. Garcia explained that the title and the song lyrics have a double meaning because in many Latin American countries “guapo” [pretty/handsome] is slang for someone who is “takes advantage of others, a quarrelsome person, someone who is violent.” Garcia highlights why this other meaning and its negation in the title is relevant to understand her view on this popular culture movement in Mexican “barrios” (poor city neighborhoods), like Tepito, where she filmed most of the documentary.

“I would like to talk about this other side because in the barrio there is a lot of richness, a lot of culture, lot of traditions. There is a strong sense of identity. There are many more positive than negative things happening there. But I don’t want to deny other things because it’s a very complex context, they do what they want to do but people treat them as the worst part of society. As someone who doesn’t have dignity. Someone who doesn’t deserve the same opportunities as others.”

‘Yo No Soy Guapo’ shows how barrios like Tepito have sonideros as their cultural reference. Garcia dedicates part of the film to look for traces of Guadalupe “La Socia” Reyes, the first female sonidero—or sonidera—of the barrio, whopassed away in 1984. Her guide to this universe is Lupita “La Cigarrita,” a popular figure in sonidero dances as a MC and a member of the sound crew Sonido Radio Voz. [1] One of the most impressive segments of the documentary shows Lupita interacting with other soundmen and soundwomen in the catholic feast of Nuestra Señora de la Merced. A crowded procession and a mass congregate, featuring dozens of people in leather jackets with soundcrew logos on their backs. The “sonidero family”, as the priest calls them inside an enormous church. Garcia made contact with her via El Proyecto Sonidero, a transdisciplinary research group from Mexico City (Delgado and Ramirez Cornejo 2012). Garcia stresses some of the characteristics of the sonideros she considers indispensable in understanding the role of these sound systems in contemporary Mexican culture, especially how they deal with technology.

“Sonideros are something authentic from the barrios, an expression created from scratch. They build their loudspeakers, fix them, paint them, and tune them so a greater public can hear the music. They get music that doesn’t exist in Mexico because it is also a matter of musical taste, so these are some of their main characteristics.”

Still from the movie

Ricardo Mendoza from Sonido Duende is a charismatic sonidero owner who shares some of his stories with Garcia, such as his commitment to play once an year in the Penitentiary of Santa Martha, because a prisoner from there had helped him recover a large amount of equipment stolen from his sonido. Besides the prison dance, the film also shows a birthday party organized by the soundcrew and his family to him, as well as his enthusiasm for sonidero culture. Mendoza unfortunately passed away after the launching of the film. Joyce talks about the role of the Sonido Duende crew in the community and as having guided the whole film production.

“Besides being sonideros, they are some of the greatest directors of sonidero culture. They connect people, making a great network, coordinating people… ‘I work with this one, you work with that one.’ They organize exhibitions, they are always doing a type of public relations work. Without them it wouldn’t have been possible to make the film.”

Still from the movie

In its final third, ‘Yo No Soy Guapo’ documents the serious problems sonideros are having with local police. Allegedly to prevent fights and shootings, the police are preventing sonideros from performing in the streets on the day of Nuestra Señora de la Merced, a day celebrating the patron saint of the La Merced markets. This has traditionally been Mexico City’s largest annual sound system event, where two hundred sonidero crews would meet in a large square to demonstrate the power of their sonidos to the population (and potential contractors). Elvia “La Guera”, a soundwoman from the Sonido Duende crew, takes the microphone of a sound system during the celebration to say to police: “We are dancers, not criminals. We have been working for 48 hours without sleep, non stop, to be here”. Mendoza summarizes the feeling of the sound operators: “Sonideros will not all be stopped. They won’t be able to. It’s like stopping… a nation.” Joyce Garcia interprets repression by the authorities as something resulting from the characteristics of sound systems in general. Shutting down of large street dances is becoming prevalent all over Mexico, although sonideros always adapt their tactics to keep operating. [2]

“The sonidos here in Mexico—and in theory also globally—are a cultural counternarrative, a counter-offering. It’s a revelry, it’s an affront to the system and to capital gains. It’s something that comes from people with the least means, the most impoverished ones. It’s something mostly improvised, it doesn’t need mediation. It’s something that the people themselves are building and shaping. It’s not a big business that makes a big economic contribution to the market or the music industry. It’s a way of enjoying music in the streets, in public spaces, and to socialize with it, keeping it alive. So,it’s a threat to big business. Of course it’s not convenient for the authorities and neither for big business because sonideros have built their own audience, a very large and loyal audience, that claims their right to the culture, to entertainment, their right to live, their right to public space.”

Joyce Garcia also talked in the interview about how her film’s has been received and how this culture is becomingmore recognized, of Mexican people reclaiming the streets through this collective experience.

“It’s a very powerful culture that many people follow, not just in Mexico City but in the whole country, and I felt people didn’t give it the importance it deserves in the study of popular culture and cultural identity of people from the poor areas of the city. For me it is such a beautiful feeling to see how people are receiving the film, identifying themselves with the right to enjoy life, giving value to their lives and reclaiming this space that is ours. These streets that are ours and the right to enjoyment, not just to survive but to live with intent, to create deep connections with the people we live with and with our spaces. It’s a very strong call to say: “Don’t let it fade away”. The film is concerned with the feelings of others because our strength is more valuable and more powerful when we are together. It’s not the individuality, but the collectivity that creates the dance and this space that is shaped explicitly to express ourselves, to be free, to be who we are, to coexist with the people, to reclaim our identity.”

Mexican sonideros have built a large musical network across Latin America, playing tunes from Colombia, Peru, Chile, Cuba, Venezuela, and also from their own country. They made this rhizomatic and transnational web digging tunes and travelling to other countries to find out new songs to make people dance. Over the years, they made creative adaptations like slowing down instrumental tunes from 33 rpm to 20 rpm to “better accommodate the pace of Mexican dancers” (Barrios 2022). The release of the new compilation “Saturno 2000” by the German label Analog Africa, brings some of these sonidero dance classics to our ears. Moses Iten has investigated the impact of this slowing down of fast-paced Colombian cumbias by the sonideros on cumbia production both locally and in Argentina, where it has strongly influenced the creation of cumbia villera (Iten 2021). During fieldwork in Mexico City, Moses first met Joyce Garcia.

In the final segment of the interview, Moses Iten talks about the richness of this culture and Joyce Garcia highlights the relevance of the research on this subject.

MI: “I’d like to give thanks to this project and the film. I hope it can attract more interest, internationally too. There are many other things we could talk about and ask questions about, so many things that this film touches on. I hope that people see this documentary as an open door to this universe—even for the people who are in the middle of it—because there are so many things you can’t catch all at once, so many layers. Thanks a lot, I hope you keep making films like this.”

JG: “Yes, many thanks, Moses, and Leo, how nice to be in this space and how nice to meet you, because I already met Moses, many thanks for the work you all are doing because it takes a lot of patience, a lot of work, lots of love and care. I know all this research, all the people who take their time to study this subject, to amplify it, have to make connections and improve the networking. Otherwise, it will be an isolated effort and I think this is something that is collective, to make a collective network, collective thinking, that inevitably brings us closer.”

At the end of ‘Yo No Soy Guapo’ there is a celebration of the power of sonideros, stressing this cultural rhizome with other countries in a 4-minute “endoclip”—or an “endo music video”—that is, when the song dominates the sound track like a music video and is played in full, with the images provided by the film crew (Vidigal, 2012). The tune is the Colombian hit ‘Cumbia de la Paz’ recorded by Chico Cervantes. The images from a lively sonidero dance in Mexico City are edited on this big sonidero hit with the remarkable lyrics written by José Barros, one of Colombia’s best known and most prolific composers of cumbias: “Love, I want romantic love/ I want sublime love/ I want cumbia love / To feel something mysterious / Voices that scream at me / That call me / To dream a profound dream /Where to look at the world with the love of cumbia / Sublime ritual of the Pocabuy [3]/ Who in the circle of cumbia [4] said goodbye /To the brave warriors / Who died there, who died there/ With the peace of cumbia / With the peace of cumbia/ Cumbia/ Born in your soul / Cumbia / Peace and love / Cumbia / No more aggression / Cumbia / May love live.” [5]

Still from the movie

Yo No Soy Guapo is available on Vimeo on Demand at this link. The first 20 readers who will share this blog on their social media will receive a batch code to watch the film for free (after logging in to their Vimeo account). Please send a screenshot of the sharing to soundsystemouternational@gmail.com to receive the code.

To read about the sonidero culture which inspired Joyce Garcia’s film, we recommend the book Sonideros en las Aceras, Vengase la Gozadera edited by Mariana Delgado and Marco Ramirez Cornejo (2012). This is freely available as an e-book, and it features the work of a collective of researchers and artists behind the blog El Proyecto Sonidero. For some extra insight about the photographies forming part of El Proyecto Sonidero, read the interview by Mark Powell with the Brazilian photographer Livia Radwanski (Casemajor and Straw 2017) [6]. Mariana Delgado was also interviewed by Moses Iten for a radio documentary broadcast on ABC Radio National called ‘The Sound of Cumbia’, available at this link.

Leonardo Vidigal is Professor of Film Studies at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil. He is also a founder of Sound System Outernational research group, and a member of Sonic Street Technologies team and Deskareggae Sound System team.

Moses Iten is a DJ (selector)/producer and PhD candidate at RMIT, Melbourne, researching digital cumbia and sound system culture. He is Foreign Languages Editor of Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture and performs around the world as Cumbia Cosmonauts.

Notes

[1] Lupita wrote a text in the book Sonideros en las aceras, véngase la gozadera entitled “Oración del Sonidero: Gracias a Dios” (Sonidero Pray: thanks God).

[2] See this blog by SST Mexico team member Linette Rivera about the sonidero tactic of using small very mobile sound systems in the barrio of Tepito to evade police shutdowns.

[3] Pocabuy is an Amerindian people from the northern Caribbean coast of Colombia. The author of the song José Barros claims cumbia as a ritual dance “born in the land of the Pocabuy” (Salcedo Ramos 2017), hence this reference . The origin of cumbia is contested however, with the most accepted theory that it is a blend of indigenous, African, and Spanish music (Fals Borda 1986, 132b; Wade 2000: 60-61). Fals Borda points out that Amerindian funeral ceremonies are one of the occasions to hear this music, hence the lyrics “to the brave warriors who died there.” However it is likely the composer José Barros was also addressing the horrific political violence which engulfed Colombia—especially in his part of the country on the northern coast—during much of the twentieth century. In another cumbia called ‘La Violencia’, Barros directly referenced the political violence in his contemporary Colombia.

[4] Cumbia can traditionally be danced in a circle—or rueda (“wheel”) in Spanish—and is an idea forming part of cumbia’s creation myth (Wade 2000: 60-61).

[5] “Amor, quiero amor romántico/ Quiero amor sublime/ Quiero amor de cumbia/ Sentir algo misterioso/ Voces que me griten/ Alguien que me llame/ Soñar un sueño profundo/ Donde mire al mundo con amor de cumbia/ Ritual sublime de los pocabuy en la rueda de la cumbia se despedían/ De los bravos guerreros/ Que allí morian, que allí morian/ En la paz de la cumbia, en la paz de la cumbia/ Cumbia/ En tu alma nació/ Cumbia/ La paz y el amor/ Cumbia/ Sin mas agresión/ Cumbia/ Que viva el amor”

[6] This remarkable book is available in PDF at this link.

References

Barrios, Maria. “Saturno 2000” Tells the Story of Mexican Sonideros. 2022. Bandcamp Daily. https://daily.bandcamp.com/features/saturno-2000-la-rebajada-de-los-sonideros-feature. Accessed 02/04/2022

Casemajor, Nathalie and Will Straw. 2017. “The Visuality Of Scenes: Urban Cultures And Vi-

sual Scenescapes.” Imaginations 7:2. http://dx.doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.VOS.7-2.11

Delgado, Mariana and Marco Ramirez Cornejo, eds. 2012. Sonideros en las Aceras, Vengase la Gozadera. Mexico City: Tumbona Ediciones.

Fals Borda, Orlando. [1986] 2002. Historia doble de la costa: Retorno a la tierra (parte 4). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, El Ancora Editores.

Iten, Moses. Mexican Sonidero Sound System Culture in Times of Covid-19. 2021. Dancecult, vol. 13, No 1. https://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2021.13.01.12 .

Iten, Moses. 2021. The Roots of Digital Cumbia in Sound System Culture: Sonideros, Villeros, and the Transformation of Colombian Cumbia. Journal of World Popular Music, 8(1), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1558/jwpm.43089

Iten, Moses. 2015. ‘The sound of cumbia’ in Earshot, ABC Radio National. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/earshot/the-sound-of-cumbia/6913882. Accessed 19/05/2022.

Salcedo Ramos, Alberto. 2017. ‘Y sigue la música, José’. Radio Nacional de Colombia. https://www.radionacional.co/cultura/y-sigue-la-musica-jose. Accessed 19/05/2022.

Vidigal, Leonardo. 2012. Música Popular e Endoclipe nas séries documentais televisivas. IV Encontro de Pesquisadores em Comunicação e Música Popular. São Paulo: Musicom.

Wade, Peter. 2000. Music, Race , and Nation: Música Tropical in Colombia. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.