The struggle for spaces to play

One of the most common issues for SST cultures around the world is certainly the difficulties to find spaces to play, which affects literally every scene we are researching. This is caused by a combination of reasons, including middle class disdain for street cultures, institutionalised racism against Black music, and widespread urban gentrification. As a result, anti-rave laws and noise abatement regulations are increasingly common, endangering the very existence of sonic street technologies. This blog focuses on our research in the UK, where both younger and elder sound systems struggle to find venues to play. This is threatening the very existence of the culture. Universities and cultural institutions could help and prevent this from happening.

by Julian Henriques and Brian D’Aquino

Sonic warfare [1] takes many forms, not least the battle for spaces to play. Historically, sounding out has always been about claiming space – for those not enjoying the privilege of owning it. Carnivals and festivals provide a chance for the temporary territorialization of supposedly public spaces. That is why sound systems have always been mobile sets of equipment. The sonic medium has proved the best for these occupations.

Access to spaces to play has always been an issue, not just in the UK but around the world. It’s probably getting worse. Noise restrictions, police curfews, local authority regulations, privatization of public spaces, licensing laws, gentrification and outright the banning of dances make it increasingly difficult to play out. This is a common story around the world, from London to Kingston to Mexico City and Barranquilla, where sound systems are criminalized, fined, and even seized when they dare to play out.

The war on noise

Usually understood as a matter of personal taste and mutual respect, the issue of noise is in fact deeply rooted in the class and race divide. In the West, noise restrictions have historically been directed towards working class sonic manifestations such as manual work, vendors and street music, culpable of intruding intellectual work and the right to rest of the middle class. In his well-known ranting entitled On Noise, German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer lists “hammering, the barking of dogs, and the screaming of children” as “abominable”, arguing that those who are unsensitive to noise “are not sensitive to argument, thought, poetry or art, in short, to any kind of intellectual impression”, a condition he ascribed to “the coarse quality and strong texture of their brain tissues.” [2]

While in the Old World the whole concept of noise has been organized along the line of class division, in the New World it has contributed to organize Black enslaved life in those territories where Western wealth originated. From the terrifying crack of the whip to the liberating whistle of the Maroon’s abeng, the sensorial geography of slavery reveals how sonic warfare contributed to shape New World’s soundscape. Here, the war on noise has been just another tool to consolidate colonial domination and exploitation of POC and Black people’s life and time. This is certainly the case with drumming and chanting banned among slaves throughout the New World due to the owner’s fear of conspiration and revolt.

Trelawney Town Maroon settlement in Jamaica. Source: web

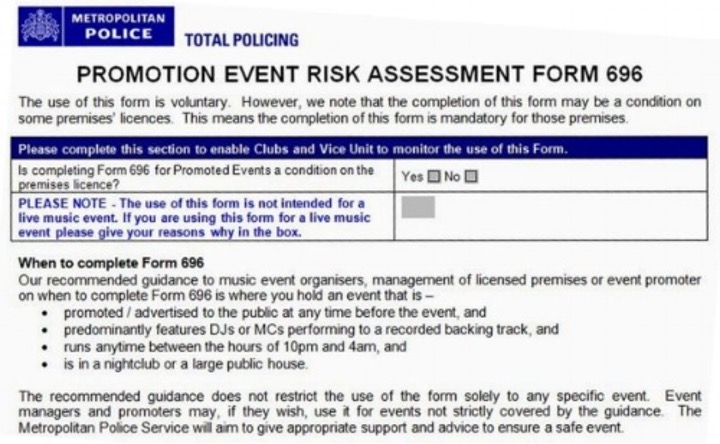

In the twenty-first century, the echo of these prohibitions reverberates through the widespread belief that Black people are generally louder and noisier than their white counterparts. This is what J.L. Stoever calls the “sonic color line.” [3] In the UK, the entanglement of race and class divide in the classification of certain sounds as noisier (and therefore more dangerous) than others is also reflected in the institutional hostility towards Black music genres such as Grime (before it went mainstream) and currently Drill, as epitomized by the form 696. Significantly, artists of both genres have credited sound systems as part of their own lineage. Therefore, it could be said that sound systems’ struggle to play out in the 1960s inaugurated six decades of sonic racial profiling which have tried to silence Black expressive cultures in the UK.

The notorious Metropolitan Police Form 696 in force between 2008 to 2017. Non-compliance would allow the police to prevent the event being granted a license.

Creating venues

As Papa Face of Brixton-based Mafia Black sound system recalled during SSO#8 reasoning session, held at Goldsmiths in November 2022:

When I started, it really was basically played at the school, like, school classrooms. And then we moved on to parties – house parties… But it was very difficult to actually play in clubs, especially with our colour, we would never be able to play there.

The experience of living in a de-facto segregated society prompted sound system owners to create their own venues where they could play out their sets and the community could gather to the sounds of R’n’B, Soul, Ska and Reggae. More than just entertainment, it was the pressing need to recreate communal bonds in a hostile environment while keeping in touch with what was happening ‘a yard’ in terms of music and trends to inspire them. As Clive Allick from Moa Anbessa sound system explained:

Sometimes there were no venues for us to play. We would go and create a venue. Meaning we would go find a derelict house, lick [sic] down the door and go inside and string up the electricity from the street and we would create the place where we could invite the public.

In the UK, the practice of creating independent (and often illegal) spaces to dance eventually passed the baton from reggae sound systems to multicultural acid house and jungle raves in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Most famously, Simon Reynolds has described this as the hardcore continuum, a peculiar UK adaptation of Jamaican sound system culture, where pirate radios eventually replaced actual sound systems and raves would happen on air [4]. Nonetheless, physical sound system gatherings didn’t fade out. Nor did the repressive arsenal used to silence them.

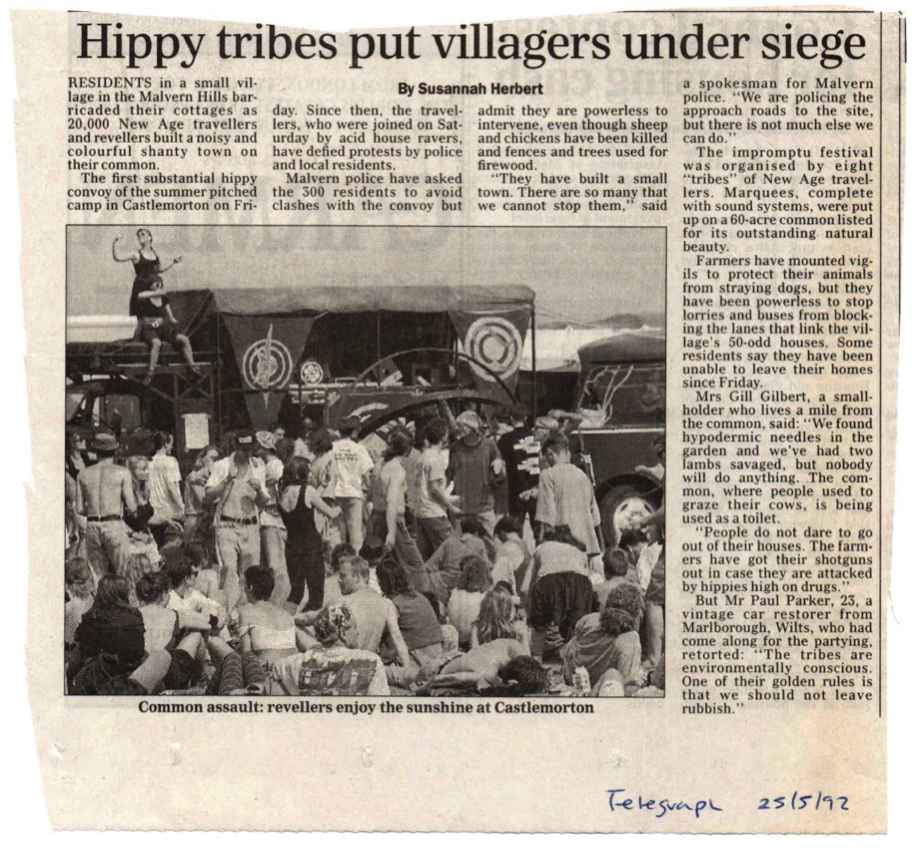

Newspaper article on the 1992 Castelmorton rave. Source: bcharchive.org.uk

In May 1992, members of the Spiral Tribe collective were arrested and charged for the infamous Catlemorton rave. The trial (one of the longest and most expensive in British history) led to the introduction of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in 1994, which included a bizarre attempt to outlaw music made of “repetitive beats,” with the clear intention of clamping down the free party movement in the UK. As a side effect, Spiral Tribe members relocated to Europe, igniting the free tekno movement that would become the biggest music subculture of the 2000s in mainland Europe. Significantly, they had appeared in court wearing T-shirts with the slogan “Make some fucking noise” – perfectly understanding what the point was. The struggle goes on in France and Italy up to today.

UK sound systems today

Reggae music has slowly gained its place in the British music landscape since at least the 1980s. But for reggae sound systems the future currently doesn’t look very bright – more the repetition of a dark past – mainly due to the lack of spaces to play, in London and elsewhere. As Moa Anbessa puts it:

History keeps repeating itself. And now we find ourselves in these situations. We haven’t got nowhere to even dance anymore. We ain’t got no clubs.

Through our research in the local area, including SSO#8 and SSO#9 events, we found there was a time when sound systems had outgrown blues and house parties, when church halls were a haven for Lewisham sounds, for instance. As Papa Face recalled during the event:

Church halls were the main sources of spaces to play in. You know, I remember listening to Shaka and Lord David at Clapton church hall. Whappy King used to play in a place up in Brixton Hill, also church hall.

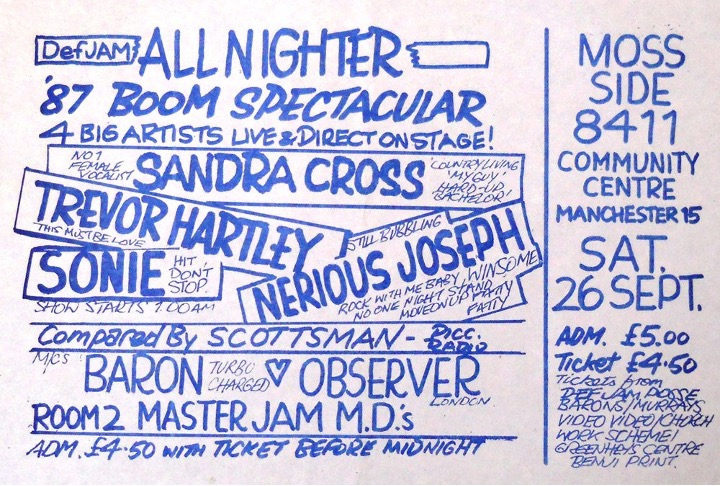

Moss Side Community Centre, 26th September 1987. Courtesy of Manchester Digital Music Archive

Currently, the churches have reverted to their original purpose with African congregations. As several of the elders told us, despite many Caribbean families owning their own homes, it is a great sadness that this idea of ownership did not extend to community or arts centres. There are virtually none in the UK. As Kiera from B.O.S.S. added:

How can we think about way to actually own space and dominate space for sound system culture to thrive? Because I feel like it’s one of the biggest things we come up against is actually being able to hold space and we often have to do it illegally or work around things.

Circumstances and demographics also change. COVID-19 restrictions meant that many sounds around the world had to leave their boxes in the garage to play out clandestinely at small parties with a laptop. In Jamaica, this has also caused many sound systems to scale down their operation by selling part of their equipment in favor of more manageable powered speakers. In the UK, it has caused many independent, small to medium-sized venues to close.

The upshot of all this is literally to cramp up and shrink the culture. As one sound man told us: “How are the Youngers going to know what they’re missing when they’ve never had a chance to hear a proper sound system in a session.” So, they are content with making and listening to music with what’s available to them – phones and earbuds. No wonder the culture is in danger of dying out. Younger sound systems face this even more directly as they put effort into building their own brand. As Tudor Lion of Creation Rebel sound system observed during SSO#8:

The greatest sabotage that we’ll face is actually not having anywhere to play the music in the next three years. Two venues out of three that I’ve played in in the last year have closed down. West Indian Centre, Leeds. Brixton Mass, London. Countless venues in Brixton… Loads of people will keep coming [to the sessions]. The actual thing will be not having a single place to play music above a certain decibel, past a certain hour, without everyone having their identification given.

Institutional Support

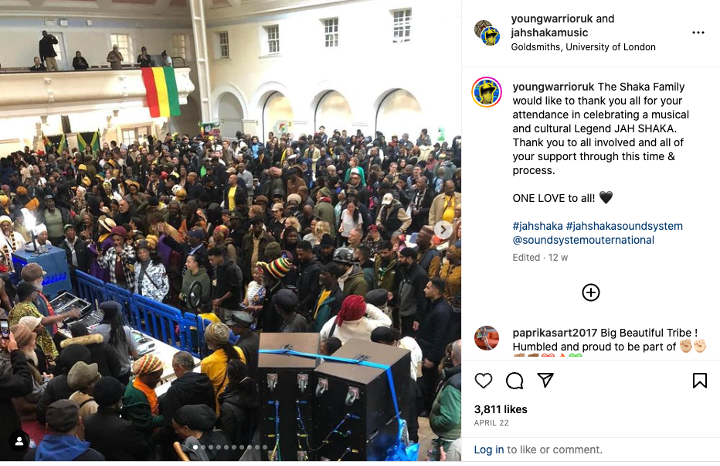

This lack of spaces to play gives an extra responsibility to universities and colleges. These often say they are “open to the local community” but in practice that often amounts to nothing. With SST located at Goldsmiths we have been trying to change this with the SSO events in the college, which have always tried to host a local sound system dance alongside conference talks, workshops and screenings. Also, we were very pleased to host the recent Nine Nights event for the late great Jah Shaka.

Instagram post from Young Warrior son of Jah Shaka about the Nine Night

Jah Shaka’s Nine Night celebration gave the college the opportunity to pay a tribute to an internationally influential Black British soundman and artist who was also local to Lewisham. It also gave the extended sound system community a much-needed chance to gather and celebrate the life of one of the true heroes in the business the way they favoured – by chanting, drumming and playing sound system. People reached the event from across the UK and Europe just to pay homage to Shaka, with the strongest contingent being of course very local – literally from across the road. Although a bit overcrowded at times, the event progressed smoothly and with several very moving moments, as captured by plenty videos and pictures circulating on social media and whatsapp.

View this post on Instagram

More IG comments, this one from DJ and Nothing Hill Carnival board member Linett Kamala.

We tried to do something similar when SST presented at the EXOCITE/4S Conference in Cholula, Mexico, in December 2022. We had a sound system workshop and dance with local sonidero Sonido Axel and some guest selectors and dancers at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Puebla. Besides enlightening the audience about a sonidero set up, the current style of music they played and so on, Axel also played an amazing set which prompted wild dance moves from both conference attendees and the local dancer’s gang Huesos. Despite being local to the college, at the end of the session Axel commented: “I never thought I would have been able to play in the campus…. Never!” Security staff and cleaners also thought the same when they saw the truck from one of their favourite sonideros entering the campus early in the morning for the set up.

Sonido Axel stringing up at Universidad Iberoamericana in Puebla, Mexico, December 2022. Image (c) Brian D’Aquino

These are just two examples of how universities and colleges can support the popular culture that is often local to them, not just with offering institutional recognition but also providing actual spaces to play. With sound system dances being currently an endangered niche in the entertainment industry in the UK, their cultural value far exceeds their financial return. Colleges have spaces and facilities that could be easily hired for free or at discounted rates for community events and celebrations to make sure that the culture that has enriched the lives of so many people does not die out. Without spaces to play there is no future for the culture.

Notes

All quotes from soundmen and soundwomen are from SSO#8 UK Reasoning Session event, available on YouTube as a research documentary.

References

[1] The term “sonic warfare” has been most famously used by British scholar and music producer Steve Goodman in his 2012 book. See Goodman, Steve. Sonic warfare: Sound, affect, and the ecology of fear. MIT Press, 2012.

[2] Schopenhauer, Arthur “On Noise”, in Parerga and Paralipomena: Short philosophical essays. Vol. 1. Clarendon Press, 2000.

[3] Stoever, Jennifer Lynn. The sonic color line: Race and the cultural politics of listening. NYU Press, 2016.

[4] Reynolds first developed his idea of the hardcore continuum in a series of short essays published on The Wire magazine in the 1990s. See https://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/essays/the-wire-300_simon-reynolds-on-the-hardcore-continuum_introduction