Researching with Purpose in Urabá, Colombia Pt. 1

A significant branch of the SST research effort in Colombia is focused on Urabá, in the Northwestern part of the country. Since 2021, the Urabá Sound System collective has been pushing for the cultural recognition of the picó (the home-grown sound system of the Colombian Caribbean) as a powerful community tool for implementing social cohesion and facilitating the peacebuilding process. Their work has been the subject of ongoing collaborative research culminating in the documentary ‘Sonando con Proposito’ (‘Playing with Purpose’) that has been screened in five Colombian cities. This three–part blog by Dr Brian D’Aquino sums up the ongoing Urabá project.

(This blog is also available in Spanish at this link)

by Brian D’Aquino

It’s May 2023 and I am flying from the UK to Colombia for the shooting of a research documentary on picó culture. As the film producer, I am not exactly at ease during the eleven-hour flight. Despite my best effort, the production schedule I am leaving with is not much more detailed than the actual commitment to shoot the film. I have carefully prepared the required documentation and compiled template interviews for several potential interviewees’ profiles. I previously co-worked on two more SST research documentaries in Jamaica with encouraging results. Altogether, this gives me some confidence. However, this is my first time leading a film project, in a Spanish speaking country, and in an environment I am not familiar with. After an overnight stop in Bogotá to meet the film crew and participate in some technical preparations, we boarded a tiny airplane heading to our destination: Apartadó, Urabá.

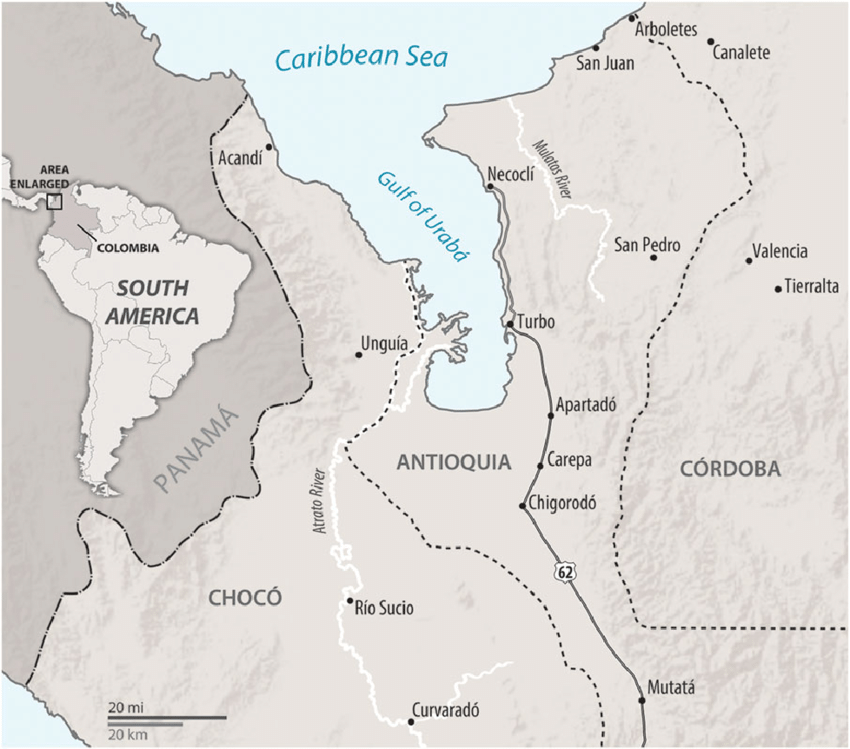

Urabá is a Black and Indigenous populated region in Northwestern Colombia, part of the Department of Antioquia. This Caribbean region is home to a vibrant local variation of picotera culture with unique music features and a rich cultural heritage, spanning several decades and deeply intertwined with the complexities of the local social and political history. Since 2021, the Urabá Sound System collective has been pushing for the cultural recognition of the picó as a powerful community tool for implementing social cohesion and facilitating the peacebuilding process. Over the course of four years, this work has not only involved local practitioners and the community at large, but also institutional entities such as Comisión de la Verdad, Fundación Mi Sangre, FUNDASEVIDA, OIM– Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, Instituto Municipal de Cultura y Ciudadanía de Apartadó, La Red Nacional de Mujeres Afrocolombianas Kambirí, La Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz (JEP), among others, eventually reaching out to the University of Antioquia, the German Institute CAPAZ, and establishing a fruitful dialogue with local authorities.

Map of Urabá. Source: Researchgate.

Flying to Apartadó with Ricardo Vega and Daniel Acevedo, May 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

Birth of Urabá Sound System collective

The SST project initially came in touch with Urabá Sound System via our friend and collaborator Ricardo Vega of El Gran Latido, a Bogotá-based reggae sound system with a consolidated history of sonic activism (see this trailer). In 2021, El Gran Latido was involved in the event that would eventually ignite the birth of the Urabá collective: the celebration for the 8th of March (8M) in Barrio Obrero, Apartadó.

At that time, the prospective collective founders Miladis Córdoba Rivas and Willinton Albornoz Quejada were looking at ways to involve young people – especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds – in the 8M celebrations, and more generally in the social process aimed at preventing further armed conflict. Despite acknowledging the convening power of the sound system for young people, they were not able to include a picó in the 8M programme due to a persistent ban on dances, motivated by the enduring stigma surrounding picó culture as the supposed cause of violence in the community.

Inviting El Gran Latido sound system from Bogotá somehow allowed Miladis and Willinton to circumvent the ban on sound system dances. The presence of a “foreign“ rig sparked the interest of the local community, especially picó owners who had been locking away their machines or playing small undercover parties in the countryside for a long time. The event made the community realize that peaceful sound system dances were possible. Most importantly, the ban could be got around if picós were part of a wider cultural and social agenda. They also found the prohibition had not diminished the appetite for sound system dances in Urabá – rather the opposite.

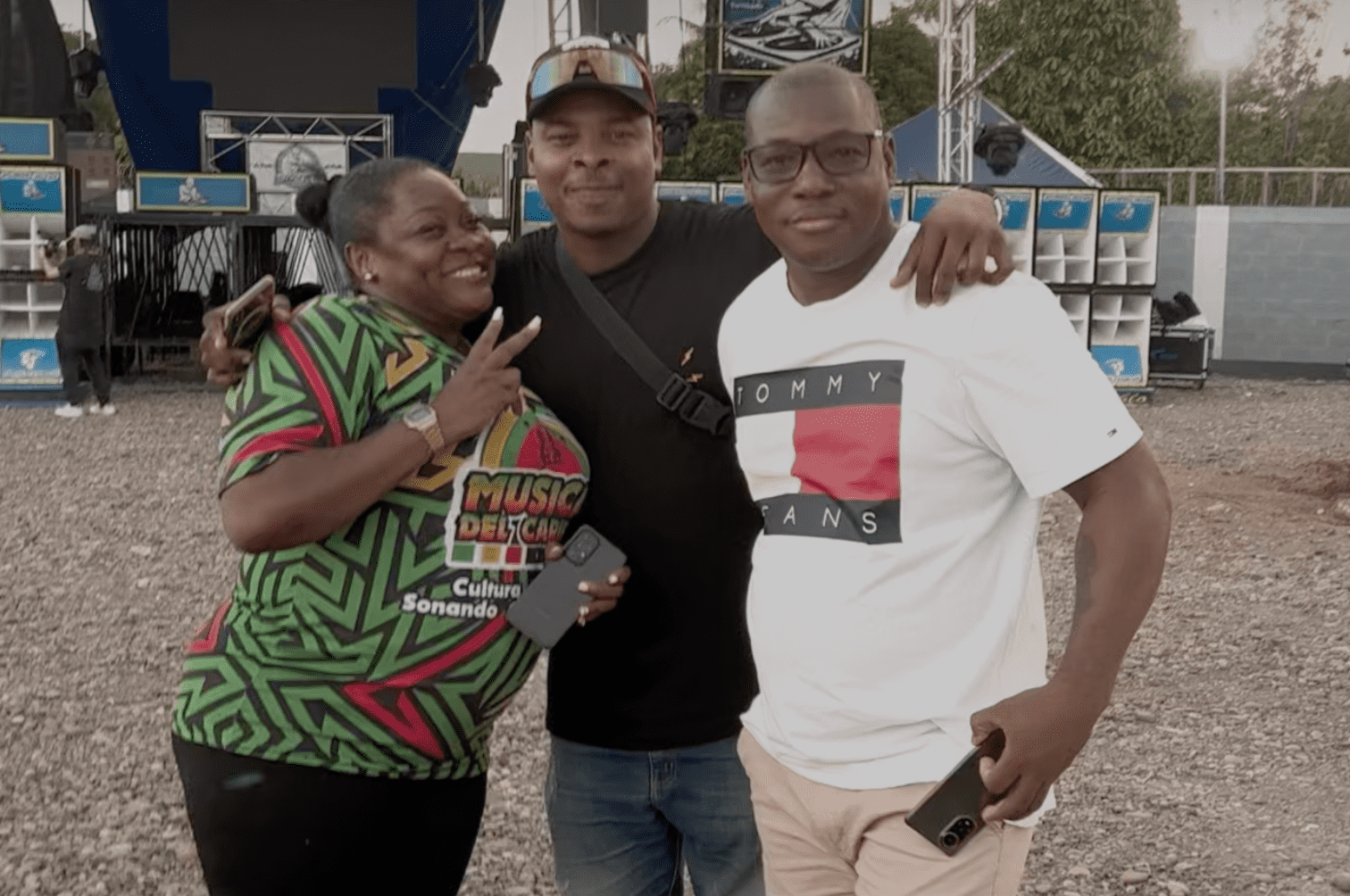

Shortly after, the Urabà Sound System collective was formed, with younger member Rafael Paz joining Miladis and Willinton’s leadership and a growing number of associated picoteros sharing the slogan Sonando con Proposito (‘Playing with Purpose’).

Urabá Sound System collective founders, left to right: Miladis Córdoba Rivas, Rafael Paz Perea, Willinton Albornoz Quejada.

Research Relationships

A non-extractive approach to research is the methodological cornerstone for the SST project. Finding ways for our work to benefit sonic street technologies cultures has been both an ambition and a commitment. We are continually looking for ways in which our research could support practitioners’ struggle to have their culture recognized in institutionally hostile environments. One way is to make good use of university’s institutional profile and summoning power.

As the project progressed, it also became clear that the research cannot do more than amplifying already existing efforts; any direct intervention is for the practitioners to make – not us. Urabá Sound System collective’s work materialized a best-case scenario to enable SST to make such a contribution.

The relationship between the SST project and Urabá Sound System was initially developed remotely through contributions to our blog. The detailed reports on the two Encuentros Picotero (‘Sound System Meetings’) held in Apartadó (2021, see this blog) and Turbo (2022, see this blog) made us quickly realize that something very powerful was going on in Urabá.

The richness and scope of the local sound system culture were striking, especially if compared with the absence of existing research or even documentation. Also impressive were the sophistication of the collective’s political strategy and their uncompromising commitment towards culture and community in a particularly challenging environment. Altogether, these elements persuaded us to prioritize the Urabá research over other possible Colombian case studies.

Picó El Firu DJ setting up the dance floor for Mother’s Day party, Turbo 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

Some Mother’s Day chilling with El Gran Tiburòn (The Great Shark), Turbo 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

One stack of picó El Grosero playing music for bar customers, Turbo 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

I first spoke to Miladis Cordoba in December 2022 while in Bogotá during my first visit to Colombia, precisely aimed at consolidating our local research network (reported in fieldwork notes blog part one and part two). Even though the torrential rain did not allow us to meet in person, the Zoom link up was very productive. As I would have learned, there is no messing around with Urabá Sound System: they usually have a very clear idea about what they want and how to achieve it. At the end of the meeting, I asked Miladis what the research could possibly do to support their effort. ‘A documentary would allow us to bring it to a next level’ – she replied without hesitation.

Producing a research documentary on Urabá’s picotera culture was in tune with SST’s methodology. At that time, the project had already started to commission and produce short films. This has proved to be a powerful way to make our research available to the sonic street technologies communities, convey a scene’s richness and dynamism to fellow researchers, and give back to the practitioners and collaborators something they could use for their own benefit. This effort has evolved into a unique collection of short films, currently being screened at conferences and festivals around the world (see this blog for example).

After a short team discussion, SST committed to the film project. In between January and April 2023, we secured a small research grant from the Research Knowledge Exchange office at Goldsmiths, which saw in the Urabá research a potential REF Impact case study. In May 2023 everything was ready, and I headed back to Colombia for the shooting of the film.

The making of Sonando con Proposito

About 24 hours after landing in Urabá my filmmaker worries were a thing of the past as we were riding motorbikes in the tropical heat on Turbo’s gravel roads, literally bouncing from one interview to the other. Sonando con Proposito was shot over six hectic days constantly travelling between the two principal cities of Turbo and Apartadó.

The rather minimal film crew included Ricardo Vega as a director and camera operator and his trusted partner Daniel Acevedo as a second camera and sound engineer. Their professionalism, sensibility and adaptability to unpredictable conditions is what allowed us to make the most of such a short schedule. The film was entirely shot on the project’s iPhone and Daniel’s reflex camera, the whole equipment swiftly fitting into two small backpacks allowing us to taxi on motorbikes as per the local fashion.

As I have learned, practitioners can have a very mixed reception for researchers’ interest, ranging from curiosity to suspicion. In his 2022 book on metal music in the Muslim world, scholar and music maker Mark LeVine advocates for a ‘race of musicians’ (borrowing the expression from Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango) which enables intercultural dialogue based on a ‘broadly common experience’ [1]. This will probably sound naïve to ‘pure’ academics. Nonetheless, the existence of such an ethereal communal bond will be familiar to any researcher with a practitioner background.

In my case, having run a sound system for twenty years – Bababoom Hi Fi based in Naples, Italy – usually allows me to break the ice and engage with other practitioners in mindful conversations precisely on the basis of shared specialist knowledge. To my surprise, in Urabá that was just an extra kick.

Interviewing speaker builder and pastor Heriberto Alvarez aka Cartucho at his workshop, Turbo 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

Interviewing Edwin Cuesta owner of El Firu DJ at his workshop, Turbo 2023. Image: Ricardo Vega.

Interviewing Dayner Becerra owner of La Nueva Ley, Apartado 2023. Image: Brian D’Aquino.

We filmed workshops, dances, private homes, and sound system rehearsals. Miladis, Willinton and Rafa greeted us with incredible generosity, offering the best support we could have asked for and literally opening any door we could possibly be interested in knocking. Overall, the people we met were very keen, even excited to share their stories.

One of the interviewees was Guiller Mesa from the Mesa picó dynasty, founders of El Gran Juancho, unanimously credited as one of the most influential picós in the whole region. El Gran Juancho was directly targeted in the terrible 1994 Chinita massacre in the Barrio Obrero, Apartado, when 35 people were killed in their dance. After a particularly moving, one hour-long interview at his home, he stated:

Since my father started El Gran Juancho, this has been the first time an outsider showed genuine interest in what my family has been doing for about fifty years.

This comment gives a sense of the privilege – and responsibility – that this research handed me and the SST project.

Miladis with the Mesa brothers from the Mesa dynasty, picó El Gran Juancho. Left to right: Luis Alberto Mesa Castillo aka Beto Man, Elkin Mesa Castillo, Miladis, Giller Mesa Gaviria. Image: USS.

Trust, Privilege and Responsibility

The good reception and trust the SST project was granted was entirely due to Urabá Sound System’s intercession on our behalf. This reflected how much the collective’s work was recognized by the local picotera community – both practitioners and fans. The practical achievements of the collective’s effort were indeed very visible – and they could even better be heard.

Permits for dances were being issued again, and tuning sessions for the sound systems (a frequent cause of dispute with local authorities) were to some extent tolerated. In some Turbo neighborhoods there were picós installed literally at every crossroad, providing loud music entertainment to bar customers and passersby. Overall, the feeling was of that of a long-awaited culture resurgence, the energy blowing in the air despite the ever-present challenges.

Urabá Sound System at Radio Puerto Stereo, Turbo 2023. Image: Brian DAquino.

Left to right: Prof Joel Padilla (University of Antioquia), film director Ricardo Vega (El Gran Latido), recording artist Betoman, Willinton Abornoz (USS), picó painter Barranquilla, Brian D’Aquino (SST), Miladis Cordoba and Rafael Paz (USS), musician Martin Rayo, Turbo 2023. Image: Daniel Acevedo.

The presence of a group of foreigners interested in picotera culture did not go unnoticed – in fact, it made quite a lot of noise, to use Rafa’s expression. The way Urabá Sound System took advantage of that “noise” is another testament to their political acumen. As the ongoing film shooting quickly became the talk of the town, we were all invited to two different radio shows where they could report on the ongoing process and further extend the collective’s reach out.

They also made good use of the presence of me as a foreign researcher to build a connection with the University of Antioquia – Turbo, culminating in a roundtable including picoteros, academics, and local government representatives. The massive participation of students and their awareness of the ongoing political struggle made clear that, despite all challenges, picós continue to be a living culture of paramount importance for Urabá citizens despite their age, gender, and ethnic origin.

With such a dynamic and potentially rich field, elaborating strategies to maximize the impact of the documentary became mandatory. This will be discussed in the next blogs.

About the author

Brian D’Aquino is Senior Research Assistant for the SST project. He is a researcher, sound system practitioner and music producer from the Southern side of Europe.

References

[1] LeVine, Mark. We’ll Play Till We Die: Journeys Across a Decade of Revolutionary Music in the Muslim World. University of California Press, 2022, p. xiv.