SST Visual Cultures. Trends Observed Thus Far

This article is the second part of an ongoing series on Instagram-based ethnographies investigating the visual cultural, textual, and affective norms of sonic street technologies globally. The previous post we explored some of the ways that we are using Instagram as a site to conduct ethnographic research. This week we are looking at some of the trends we have observed thus far in our visual culture ethnography.

—

Sound system cultures are multifaceted, diverse, and multi-sited phenomena that call for robust and eclectic methodological and theoretical orientations. Instagram-based research of its visual cultures had been developed in response to the collective surge in online presence across the performing arts sector due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, Instagram has become simultaneously a useful tool in situating and attending to the multitudes of ways sound system operators, aficionados and artists engage with visual means to engage with audiences. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of Instagram, along with other social media, has been a way for the sound systems community remain active. Here, we cover some of the ways that we have been using Instagram to track the cultural evolution of sound system cultures during the pandemic and beyond.

Construction of sound systems

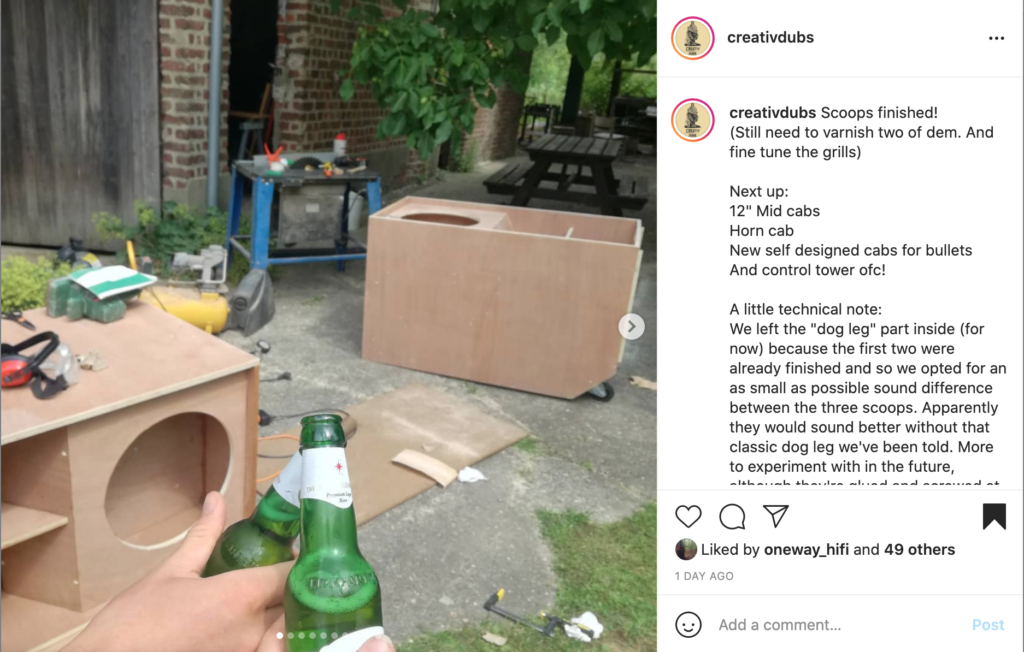

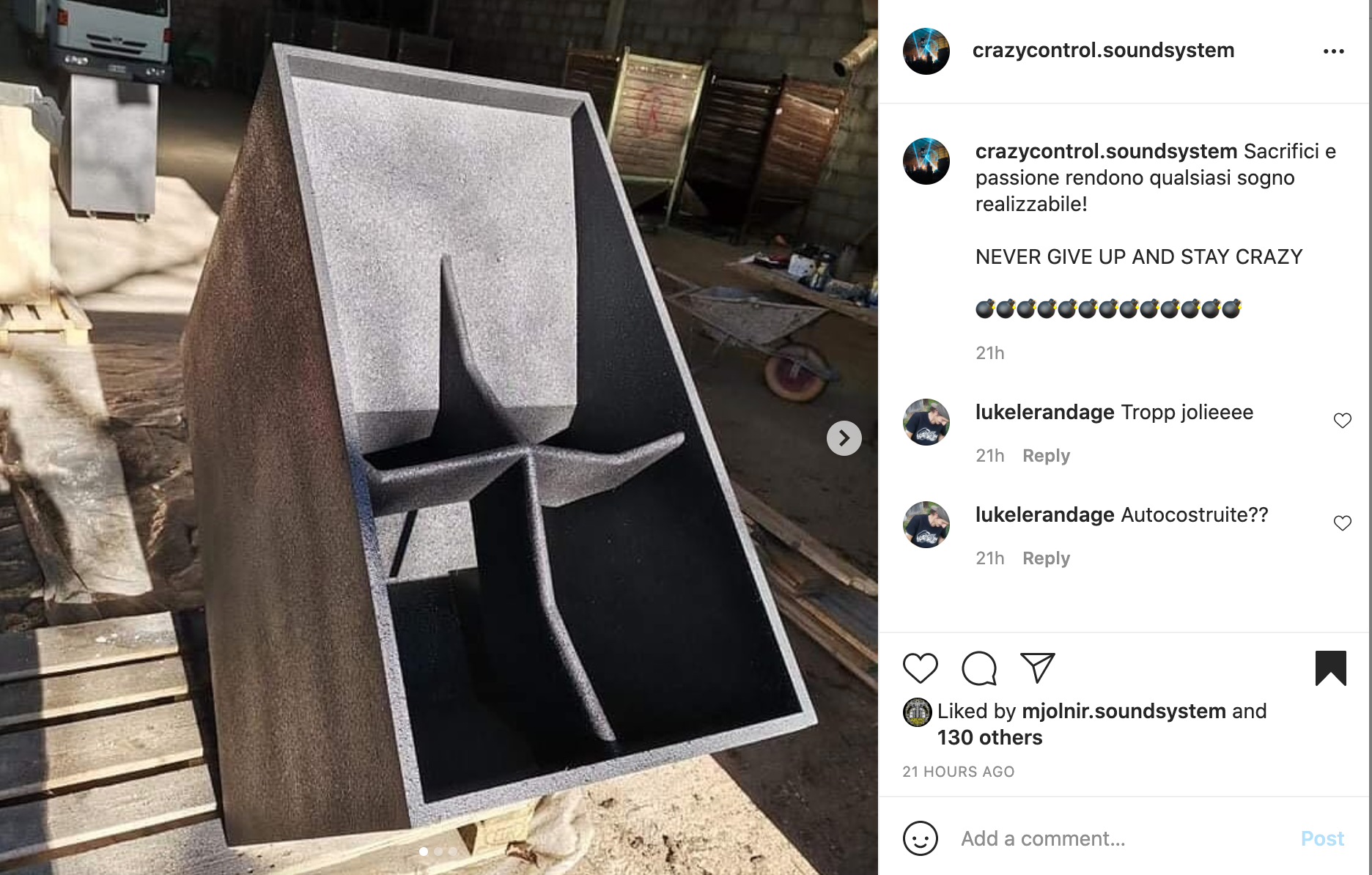

One of the features that distinguishes sound system cultures from a variety of sonic practices is the centrality of the hand-built technical apparatuses – especially the speaker boxes. Accordingly, the architecture of the sound system, its operating philosophy and construction are of particular interest. Many sound system operators, as well as equipment procurers and sellers catering to SST, often provide detailed visual archives of the progression through which sound systems are built from scratch. During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the representation of the construction of sound systems has been one of the ways that sound system operators sustained their engagement with audiences and the scene at large.

Four examples of sound system construction documented on Instagram

Four examples of sound system construction documented on Instagram

The process by which sound system practitioners build their own set offers us insights into the particularities of choices made each step of the way. In their choices of shapes, materials, design and overall architecture, we can elucidate the variety of expertise mobilized to customize the final sonic characteristics of the sound systems. In documenting the construction process through Instagram, practitioners in turn, deconstruct the sonic architecture of their making into various phases, parts and equipment. Consequently, as researchers, we are invited vicariously into the simultaneous constructive and deconstructive embodiment that practitioners employ in service of creating their sounds. Moreover, the piecemeal fashion by which sound systems are constructed illustrate the ongoing negotiations and technical knowledges that must be mediated by a plurality of socio-technical demands that sound system operators navigate – setting their creations apart from models of standardization that is the norm in many mass manufacturing contexts. The construction process further situates the uniqueness of each individual sound system and highlights the expertise and the communities of care that sustain sound systems in an ongoing way. By becoming witnesses to this process, aficionados, other practitioners, and ourselves, as embedded researchers, become part of the construction process.

When sound system practitioners showcase the construction process on Instagram, they also become part of the overall ethos and the ethic of maker culture and associated movements surrounding hacktivism, DIY cultures and repurposing. In this way, some of the ways that sound system communities navigate their status through legal-infrastructural challenges, especially that related to community building, and creating spaces for gathering and collaboration. While much of the sociocultural and economic landscape has changed, the current maker ethic that many sound system operators embody are resonant with earlier sound system-based movements that engage with broader concerns related to social and economic marginalization, such as the Exodus Collective [1].

Sound systems as landscape features

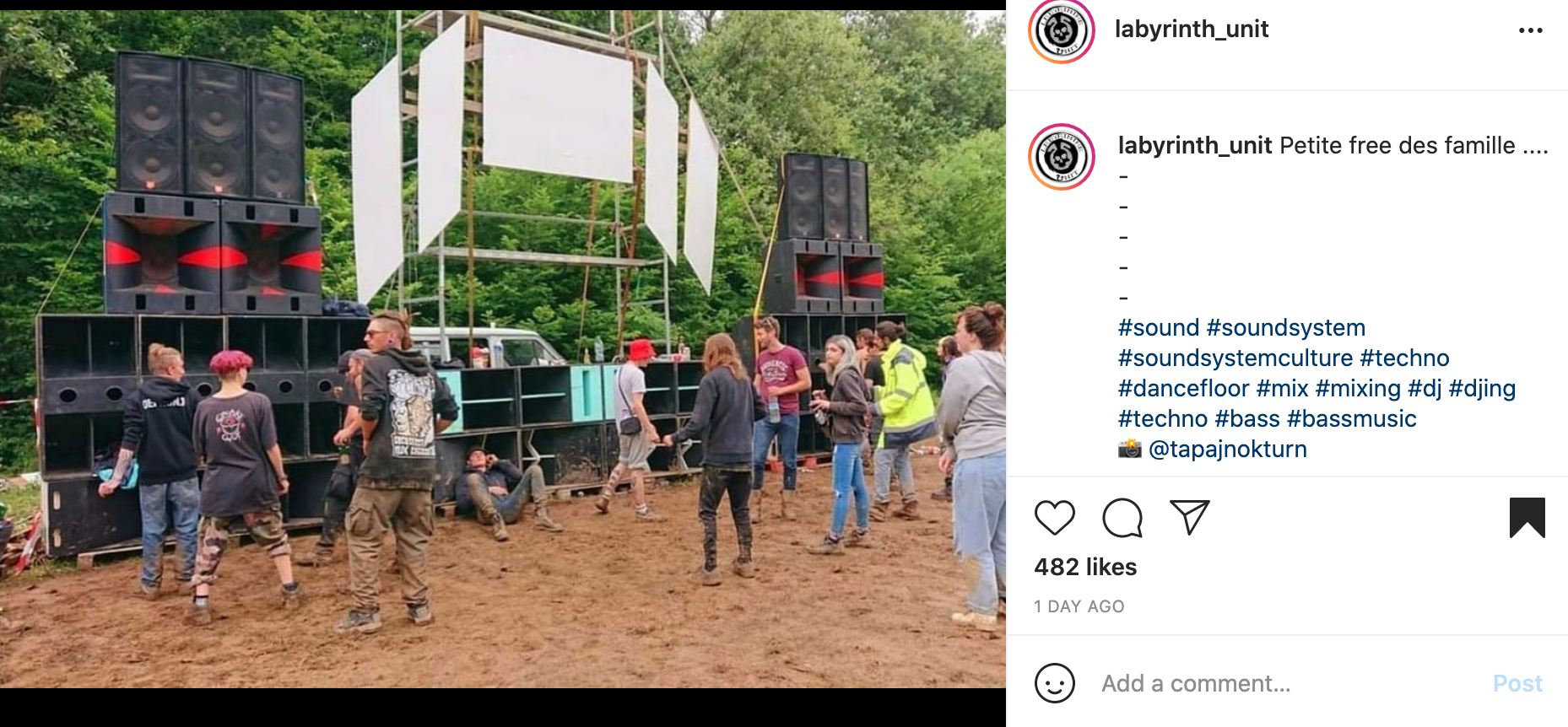

Many sound system operators like to present photographs of their sound systems outdoors, in particularly compelling sceneries that invoke a sense separation from hyper-urbanized landscapes of the city, while others show how the structure of the sound system is juxtaposed to the built environment all around. In both cases, these visuals showcase sound systems as the hybrid assemblages they are that situate and magnify the confluence of biophysical natures, technologies, and communities – such that they become, at least in a temporally and spatially contained way, rooted in the pre-existing landscapes themselves and naturalized as a feature of localized naturecultures [2].

In the summer of 2021, as restrictions eased, the focus on sound systems in the outdoors was particularly notable.

In the summer of 2021, as restrictions eased, the focus on sound systems in the outdoors was particularly notable.

These images underscore the social embeddedness and the endemic qualities of individual sound systems, and the sounds which originate from them – highlighting their intrinsic connection to place.

Sound systems often like to present themselves with a backdrop of local landmarks, and public areas where the urban environment of their point of origin is palpably salient.

Sound systems often like to present themselves with a backdrop of local landmarks, and public areas where the urban environment of their point of origin is palpably salient.

Sound system operators may also similarly portray themselves being embedded in urban environments, often close to recognizable landmarks which draw attention their function as part of a larger infrastructure of urban life. In urban settings, sound systems are subjected to numerous legal and infrastructural challenges, and consequently, their positioning as an integral part of urban life can be seen as acts of resistance. Moreover, positioning themselves within more tangibly urban environments can enable sound systems to establish themselves as landscape features, often with intrinsic ties to certain marginalized neighbourhoods and communities.

In her work, Sonjah Stanley Niaah has conceptualized a framework that she has termed ‘performance geographies’ [3]. In the context of treating sound systems as landscape features, understanding the broader performance geographies that trace the origins of sound system cultures to broader historical and contemporary Black Atlantic performance practices may also be fruitful.

Sites of community formation and dispersal

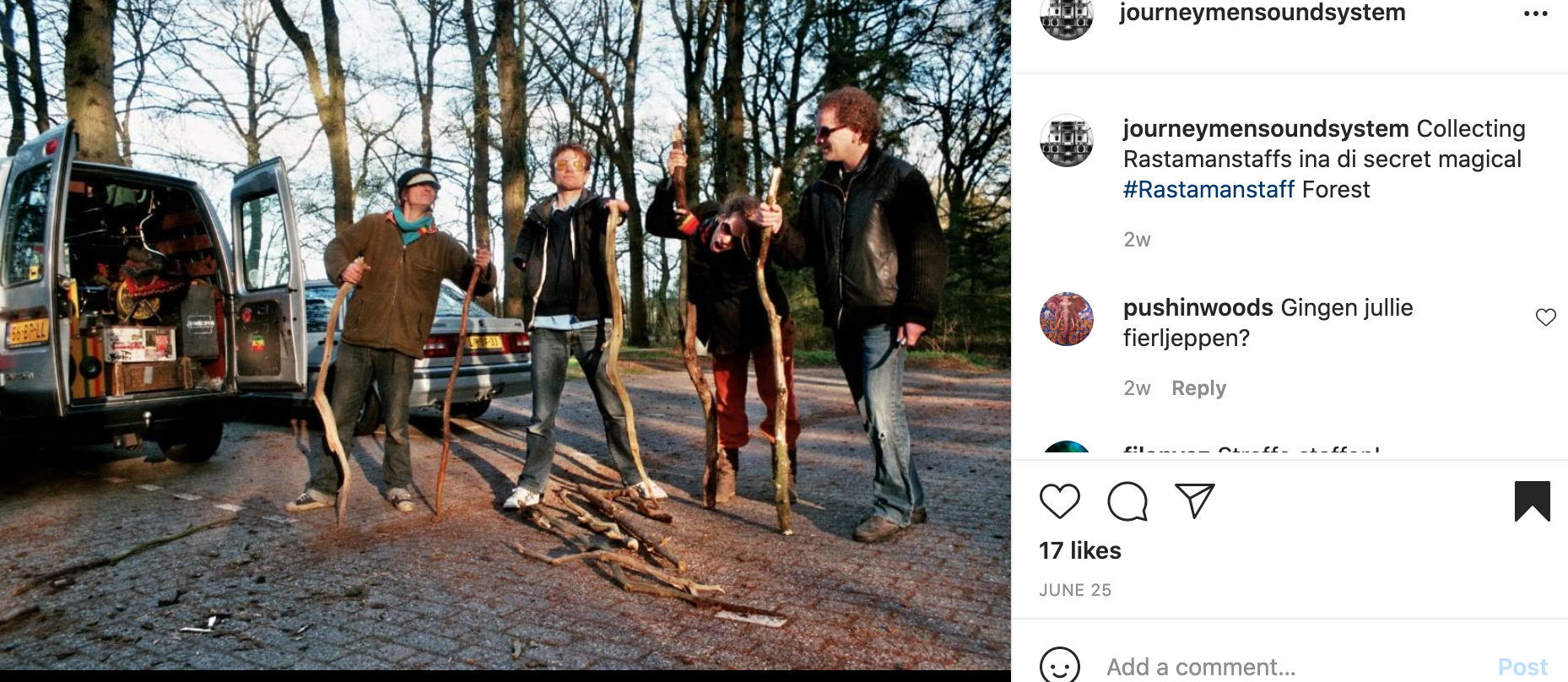

As sound systems emerge to become landscape features, they also emerge to be sites of community formation and dispersal that are mediated by the promise of the sounds, their affective and embodied echoes that resonate outward from their points of origin. However, sound systems are also hubs for their associated communities not only during the spatial-temporal contexts of events, but also through the acts of maintenance and care undertaken before and after, often involving families, friends, and other kinship networks. Especially in the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, these kinship networks surrounding sound system cultures took prominent focus.

While many such kinship and community ties experienced disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and due to increased legal-infrastructural hostility to sound system cultures, Instagram often became a place to commemorate times in the past when embodied community events had happened. This invocation of nostalgia is one of the tools of the archival process that many sound system enthusiasts as well as sound system operators employ to engage with their communities.

In their totality, sound system cultures engage with and are represented on social media platforms such as Instagram as an extension of their material presence embedded in specific geographies. While the visual culture represented on Instagram offer an insight into the ways that individual sound systems and their associated scenes evolve over time and engage with their embedded communities, it is ultimately only an aspect of the overall sound system culture and scene apparent in the flesh. Social media remains only one of the multiple strata and levels of cultural expression apparent amongst sound system cultures. The visual culture represented enable the extension of sound system cultures from beyond their socio-spatial-temporal locations to other spaces and places, which enable its survivance [4] even amidst conditions of precarity.

—

Aadita Chaudhury is a Research assistant in the SST project. She’s a writer, science studies scholar and arts-based research methodologies practitioner.

—

References

[1] Malyon, Tim. 1998. “Tossed in the Fire and They Never Got Burned: The Exodus Collective.” DiY Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain, 187–207.

[2] Malone, Nicholas, and Kathryn Ovenden. 2016. “Natureculture.” The International Encyclopedia of Primatology, 1–2.

[3] Stanley Niaah, Sonjah. 2008. “Performance Geographies from Slave Ship to Ghetto.” Space and Culture 11 (4): 343–60.

[4] Vizenor, Gerald. 2008. Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. U of Nebraska Press.