Social Work and Turbo Picós in Pasacaballos, Colombia

Through sonic street technologies, communities forge identity, claim the right to self-representation, and build bonds of belonging and solidarity. Dancing becomes political when it questions the right to public space. Playing music is political too, when it asserts the right to be heard, sparks social mobility, and embodies the aspiration to reclaim dignity through culture for racialized and marginalized communities. In Colombia, practitioners and activists’ efforts to have their culture recognized through its social implications are gaining momentum (see, for example, this blog by Urabá Sound System). This week’s contribution by Jorge Giraldo sheds light on another important process of community empowerment through picotera culture—more specifically, the traditional turbo format.

By Jorge Giraldo Barbosa

Pasacaballos is a rural district of Cartagena, located between the city’s industrial zone (locality 3) and the mouth of the Canal del Dique. It has around 20,000 inhabitants, most of them Afro-descendant. Because of this, the Community Council of Pasacaballos acts as the grassroots ethnic organization in the territory, from which the community’s cultural and social policies are developed.

For about five years now, some families in Pasacaballos have been rediscovering their love for the picó turbo and its old music, which is deeply connected to the community’s Afro-diasporic identity. Out of this initiative for social affirmation in the festive and musical sphere, the Community Council of Pasacaballos and its Ethno-educational Committee have been building a particular kind of social management and support around the picó turbo in the district.

In this blog, I reflect on the work that has been unfolding in Pasacaballos around the ethnic and cultural value of the picó turbo, through the efforts of the local Community Council and the experience of community leader Lisbeth Julio Guerrero.

Lisbeth Julio Guerrero con el picó turbo El Africano, Pasacaballos, mayo de 2025. Fuente: Lisbeth Julio Guerrero

Between Community Leadership and the Passion for the Picós

When I interviewed Lisbeth Julio Guerrero in June 2025, I encountered a young woman with a strong sense of authority and self-determination grounded in her community work. She belongs to a new generation of highly educated Afro-descendant youth. Lisbeth holds a degree in Modern Languages and a Master in Inclusive and Intercultural Education. She is a teacher, cultural organiser, and currently serves as president of the Ethno-Educational Committee of the Community Council. Among her many roles, community leadership stands at the core of her identity, something she took on at the young age of 20. She follows in the footsteps of a maternal line of women leaders, including her mother, Liris Guerrero, and her grandmother, Marina Bellido, making her leadership a socially inherited responsibility.

“My community work is rooted in the ancestral heritage of this Afro-descendant community. Pasacaballos is rich in culture—its ancestral practices make it unique: the culture, the fishing traditions. I was born into these resilient families who have always found ways to move forward.

“I began to develop a social and community-oriented sensibility, a desire to help, especially in the face of the limited opportunities available in our communities. In the past, the lack of access to education was a particularly critical issue in the territory. That’s when I started, drawing on my education and personal experience, to feel the urge to contribute—through education, through culture, by preserving local customs and traditions, and most of all, by working with the younger generations […], supporting young people in their education, and through social, cultural, and inclusive programmes.” (Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

A young woman supporting other young people—this could summarise the journey of community leader Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, who, through her passion for music and the the picós, idenitified a tool for social and ethnic affirmation: the turbos. Alongside her inherited gift for service and leadership, Lisbeth also carries a musical legacy tied to picóculture—something she sees as always having been part of her family life, so much so that she currenlty runs her own picó, El Gran Swing.

“El Gran Swing is an inheritance from my former father-in-law. He was the one who built the amplifiers for these turbos, so they could reach maximum sound output. Mr Eder was one of the pioneers in the city of Cartagena—Eder Gómez. They called him El Rey King—he has his own legacy. He was the owner of one of the largest maxiteca turbo in Cartagena. His son, my husband, is also passionate about turbos—a passion we share, especially for the sound, because what I really love is the music of the turbos.” (Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

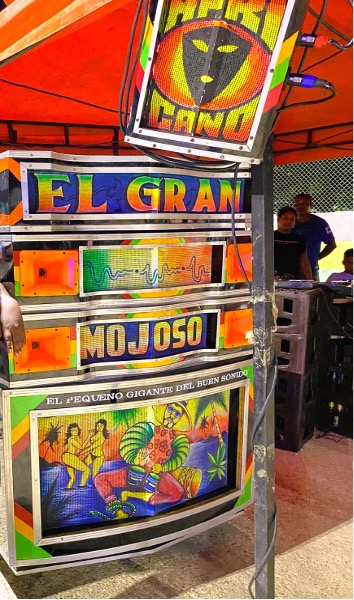

The music of the turbos” Lisbeth Julio refers to are primarily African genres such as soukous, jùjú, and highlife, along with traditional Cuban rhythms, salsa, early champeta—also known as champeta criolla—and older Antillean music styles like reggae, soca, zouk, calypso, and kompa. These are predominantly musical styles from the 1970s, 80s, and 90s—vintage sounds that continue to be played, turning the turbos into a sort of time machine.

It is worth noting that the turbos are often also referred to as picós salseros in Cartagena, and by extension also in Pasacaballos, to mark a clear distinction from the modern or fraccionado picós, which mainly play champeta, and to a lesser extent vallenato, reggaetón, and contemporary salsa.

Picó El Gran Mojoso, Pasacaballos 2025. Source: Lisbeth Julio Guerrero

Social Engagement Through Turbos in Pasacaballos

It is this kind of connection with sonic remembrance that gives the turbos such profound cultural significance for the community of Pasacaballos. The musicality of the picó turbo acts as a form of social mnemonics, contributing to meaning-making and the transmission of elements from the past—elements that matter because they form part of the community’s collective memory (Jelin, 2001).

Moreover, as an Afro-descendant community, there is a process of cultural appropriation and affirmation around the African heritage capital represented by the picó turbo. Africanness is claimed as something owned and embodied—linked to sound and to the community’s ethnic context. Associations with Blackness and African identity are reinforced as a narrative force ready to be consumed, appreciated, and expressed through diverse sociocultural forms (Giraldo, 2016). Based on her professional experience, Lisbeth Julio Guerrero puts it in these terms.

“Well, through ethno-education we began to analyse and understand the importance of knowing our roots and our sense of belonging. We [the Community Council] started learning more, and through the professional studies I undertook in my Master programme, we explored African heritage and the significance of African music in our lives. Turbos play a key role in the history of Afro-descendant people.

“The turbo was symbolic of African people—through the music and the maxitecas, which amplified these African rhythms, especially the drumming, to the highest level —it’s what connects us […]. The artwork, the vibrant colours… A turbo isn’t just a luxury item, it holds identity and historical legacy for those of us who identify as Afro. The turbos are a legacy of Afro identity and of our roots.” (Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

Picotero Dj playing at the African Heritage event, Pasacaballos, May 25, 2025. Source: Lisbeth Julio Guerrero

In this sense, the festive and musical practice of the turbos in the rural district of Pasacaballos aligns with both collective memory and an affirmation of ethnic identity grounded in African heritage.

“At the territorial level, turbos also re-signify social spaces. The K-z (or casetas, meaning local party venues) and popular street gatherings are spread across various parts of the district, with K-z Tamanaco enjoying particular renown. These are spaces where both turbos and modern picó fraccionado systems play their music. On weekends, turboslight up the streets—on Calle del Adulto Mayor, Calle del Tamarindo, Calle del Campo, Calle del Puerto (along the Canal del Dique, also known as Puerto Picó), among other key sites cherished by the local picó culture and its people—the pasacaballeros.”(Ángel Rodríguez, pasacaballero, interview, June 2025)

Given the cultural and ethnic significance of the picós for the people of Pasacaballos, the Community Council began, approximately two years ago, to develop a process of social engagement centred around the turbos, to which Lisbeth Julio Guerrero has contribute.

“As part of our work in ethno-education, we [as the Community Council] began encouraging the community to embrace the turbo—as a machine that identifies us through our history, through the passion for listening to music on these machines. It’s pedagogical—it’s about rescuing our identity, and above all, fostering self-recognition. It’s about holistic education: for those who love music, sport, culture, painting…” (Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

Activities involving the picó turbos are underpinned symbolically by the themes of cultural identity and community civic values:

“During the African Heritage Week, we sent invitations from the Ethno-Education Committee to the most representative picós of Pasacaballos—around 20 of them. We envisioned an event where we could begin to truly value the community’s historical legacy. Each crew brought their best picó, played their finest tracks on their best sound systems—the most powerful sound possible. But beyond the sound, it was about community integration and the values that bring us together, like solidarity and respect. People came dressed in the ethnic attire that connects us to Africa.”(Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

Generally, these events are organised by the Community Council of Pasacaballos. The most recent one, as Lisbeth recounts, took place during the Afro-Colombian Heritage Week in May. On that occasion, they succeeded in bringing together six picós from Pasacaballos, with a strong turnout and support from Cartagena’s municipal cultural policy through the IPCC (Institute of Heritage and Culture of Cartagena). This reflects the consolidation of a festive and culturally distinctive policy that the Community Council of Pasacaballos has been spearheading around the picó turbos. Looking ahead, the community hopes to begin a mural project that will see the corregimiento of Pasacaballos adorned—across streets and avenues—with the vivid imagery of its picó turbos.

Flyer for the African Heritage event, Pasacaballos, May 25, 2025.

Conclusions

The model of social engagement being developed in Pasacaballos aligns with wider processes of patrimonialisation of picós in the Colombian Caribbean—a topic explored in a previous blog. It stands as a community-driven response to the persistent stigma and negative perceptions attached to the festive culture surrounding the picós:

“The social stigma has always been there, really—it did not go away. As a community, when we attend these dances, we’re labelled ‘champetuos’, or seen as ‘delinquents’. These spaces are seen as not being for everyone. People who are considered respectable and attend are often stigmatised and discriminated against. For some, these events are simply associated with ‘drug use’, fights, and trouble. So, throughout history, picós parties attendants have always carried that stigma.

“When it comes to public policy, some administrations make it very hard to get permission to hold picó parties, precisely because of the problems these stereotypes cause. […] It’s never easy to secure authorisation from the authorities—but through perseverance, we manage to make the events happen.” (Lisbeth Julio Guerrero, interview, June 2025)

To frame picós as a matter of community and cultural importance runs counter to the dominant moral conventions of public policy on festivals, which often subtly reproduce racism and aporophobia.

The work being led by the Community Council of Pasacaballos—grounded in a pedagogical approach to the values embedded in the picó turbo, the events they organise, and their forward-looking projects—stands as a compelling example of socially-engaged cultural policy. It offers a model that could inspire other Afro-descendant communities in the Colombian Caribbean with deep-rooted connections to these sound systems.

African Dance and Attire Contest, African Heritage Event in Pasacaballos, May 25, 2025. Source: Lisbeth Julio Guerrero

References

Jelin, Elizabeth. 2001. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de memoria?. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Giraldo, Jorge. 2016. Música champeta y africana en el Caribe Colombiano. Revolución y cultura en la verbena y el picó. Córdoba: Observatorio del Caribe Colombiano / Grupo de Etnomusicología Circolo Amerindiano.