- #conference

- #jamaica

- #knowledge

- #practice-as-research

- #reggae

- #soundsystem

- #soundsystemouternational

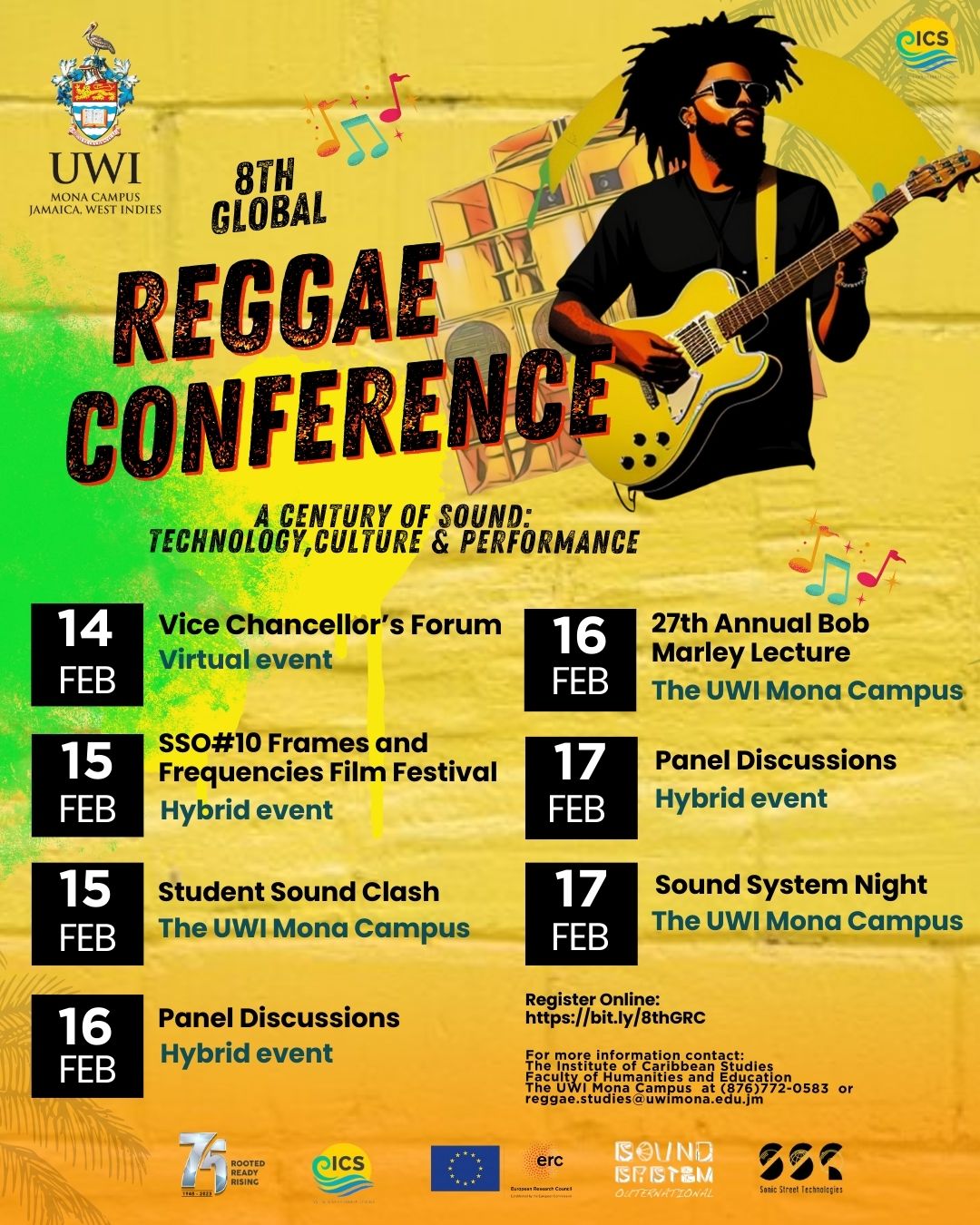

Feeling the Sound: The 8th Global Reggae Conference

The long term objective of the SST project is to establish sonic street technologies as an area of study. Therefore, having students and younger scholars getting involved is very important. We are pleased to welcome to the SST blog PhD candidate and sound system practitioner Giovanni Mugnaina from UNIBO (Italy) to report on the 8th Global Reggae Conference in the context of his first ever Jamaica trip – certainly a milestone in the career of any scholar interested in sound system culture.

As I’m writing this report I’ve just returned to London from Kingston and I’m battling with a certain nostalgia. My name is Giovanni Mugnaini and I am a PhD student at the University of Bologna, Italy. I have been promoting reggae and dub music since 2015 with my sound system, Peaceful Warriors Sound System, and I am a FOH engineer and dubmaster for a reggae band, Afreak. Therefore, for my study time abroad it was natural to contact Professor Julian Henriques and Dr Brian D’Aquino at the SST project. It was a great joy to accompany the SST team to attend the 8th Global Reggae Conference a Century of Sound: Technology, Culture & Performance at the University of West Indies at Mona, Kingston Jamaica. The following text will not be a precise report of the event, but rather a sort of diary in which I want to note down not only the experience of the conference – sincerely stimulating and humbling from an intellectual point of view – but also an account of my first stay in Kingston.

Arriving to Kingston by night

For anyone involved with reggae and sound system culture there are two locations that have the greatest historical prestige: London and – of course – Kingston.Since I came into contact with reggae and sound system culture around 16 years ago I harboured the dream of being able to visit places which have often been mentioned in reggae lyrics. The arrival by plane, after more than eight exhausting hours of travel, is signalled by the linguistic switch of my fellow passengers: “Back a yard finally”: their conversation until then held in English, it immediately slips into Jamaican. An introduction to the island mediated – who would have thought – by the vocal dimension, by speech, by new but familiar sounds, even before getting off the plane.

The first impact with the city at night is that of a very lively reality, a happily noisy environment constantly punctuated by musical flows. In fact, it feels like entering a sonic ecosystem that perpetually accompanies every activity, almost like living in sounds. The road that stretches from the airport to the city passes through Harbour View, a place that immediately reminds me of the tune Bike no Licence by Easton Clarke, in which the singer talks about his attempts to raise money for the rent and to support his children. After a night’s sleep, the first real Ital food of my life; in a small stall near Papine market, rice and peas with callaloo.

Mountain view from Papine

Kingston Dub Club, Reasoning Day, Downtown

The days preceding the start of the actual conference were spent in preparations but also visiting some fundamental places for the city’s sound system culture, first and foremost the Kingston Dub Club, run by Gabre Selassie and nestled in the hills surrounding Kingston.

The skyline view from the Kingston Dub Club

At Dub Club it is easy to meet artists who gravitate or live around Kingston; in fact, the Bob Marley tribute night we attended had the singer Jah9, the veteran Kiddus I and the band Raging Fyah passing by. The same distance between internationally renowned artists and the public seems to disappear; everyone peacefully enjoying the music in a serene and jovial atmosphere.

The next day it was the turn of another institution, the Institute of Jamaica, to attend the Grounation Reasoning Session. This longstanding institution is located in downtown Kingston, the part of the city facing the now semi-abandoned port, but still rich in music history: Orange Street, Dromilly avenue, Trenchtown Yard. The chairman was Mutabaruka, a renowned veteran broadcaster, Jamaican cultural activist and dub poet awarded in 2016 the Order of Distinction. The topic of the reasoning session was the possible strategies to revive downtown Kingston such as the valorization of creative industries. Such sessions are a regular part of the “Reggae Month” of February.

The participation to the session by academics, professionals and the general audience really gave me the sensation of witnessing politics in the etymological meaning of the term. What emerged from the session is the paradox of an island that, despite having produced musical genres that have spread throughout the world, has refused for too long to enhance their expression in its own land.

Mutabaruka chairing the discussion, Institute of Jamaica.

In the words of Tony Myers “people from other countries come to Jamaica to listen to our music, and yet we have to fight […] I’m here to stand a fight for culture to make sure the culture stay alive.”

JamOne Yard, the Living Culture

On Monday 12th we visitied Tony Myers’ yard, founder of JamOne sound system and chairman of the Jamaica Sound System Federation and a longstanding collaborator of the SST project. A real dive into the most authentic dimension of Jamaican sound system culture. In his interview Tony recalled how this is not just “music”; the sound system is a collective work where everyone can have their own role and contribute to the success: “Sound system taught us how to live, in order to run a sound system, you have to learn to be a promoter, a chef, an engineer, a builder”.

Sound system tuning at Tony Myers’ JamOne Yard.

While Tony records a video message for the conference everyone in the yard is busy; testing the sound system, preparing new speakers, unloading the van: living culture in action. Here I had the perception of how much this culture is rooted in this island, how much it is made up of knowledge acquired in the field and through experience rather than the result of formal and manual education. The sound system not only as a business but also as what Jamaicans call “livity”, a way of life which does not have fixed and formalized rules but which operates along continuities and on the recurrence of certain practices. It’s not just about music.

The Global Reggae Conference

On Wednesday the 14th the eighth Global Reggae Conference: A Century of Sound: Technology, Culture and Performance finally begins: more than sixty contributors distributed across eleven very dense panels. I immediately realize I’ve ended up in the perfect place for my research, which tries to build a theoretical framework and to reflect on the aesthetic dimension of popular culture, namely that of reggae/dub sound system culture. It may sound redundant but, in the context of philosophical aesthetics, there are few examples of such theoretical endeavour. And I must admit that I felt humbled in this sense too. For four days scholars, practitioners and elders from literally every part of the world, showed through their interventions that everything that passes through the Reggae ecosystem and its diasporic projections is not just music.

Maxine Stowe (right) and conference participants.

In fact, there is a whole cultural legacy made up of techniques, stories, mythologies, Afrocentric cosmologies, poetry and social commitment that can be denied or dismissed only for ideological reasons. In fact, in his opening message the Vice Chancellor, Sir Prof Hilary Becklesii reminded us of his fascination with the sound system and the music as a son of the Windrush Generation: “The theme [of the conference] is music to my mind and to my soul”, and then he recalled those days when

“I saw young men designing, innovating ceiling high speaker, amplifiers […] sound systems that made the soundman a hero […] The drum liberated, the bass calling us to war, and the soundman as the master of the mix in full control; this was Birmingham, not Kingston.”

The other panelists on the Vice Chancellor’s forum, Sonjah Stanley Niaah, Nadia Ellis, Julian Heriques and Brian D’Aquino, and Aleema Gray, only accentuated this feeling of seriousness and intellectual depth. This opening session was followed by music industry panel, with a VP Records’ professionals sharing their knowledge with university students.

In fact, for four days it is as if different cultures, realities, political and existential stories had all found themselves together, united by music and sound. During SSO#10 Frames and Frequencies film festival, hosted by SST on Thursday the 15th, this feeling only became more accentuated. The autobiographical nature of the short films, in addition to taking us from Jamaica to the whole world manifested an urgency: the need to tell stories and, the need to conserve – and not to preserve – memories and knowledge. One of the most impactful films was Sonando con proposito (Playing with purpose). The film tells the story of the picò culture in Urabà, Colombia, where, in a context historically plagued by violence, sound system owners formed a collective ato keep the culture alive and offer support to the community.

The non-extractive nature of the SST methodology was reflected in the scope and depth of the film programme. From BFR’s India to Urabà in Colombia, all stories had great human depth further convincing me of the intimate richness of this cultural dimension that unites a large part of the world through sound systems, picòs, sonideros, aparelhagens: cultures that I was not aware of. The final section of the screening day was dedicated to Sounds of the Future, perhaps one of the most impactful of the SST documentaries, in which some of the major Jamaican soundmen held a conversation in Tony Myers’ JamOne Yard. It was for me a very humbling experience to witness such giants of the Jamaican scene talk about the future of sound systems especially with me being a practitioner.

Global Reggae Conference poster.

Friday the 16th and Saturday the 17th were entirely devoted to panels. Among them panel#2 Sonic Media and Recording Technologies was very interesting to me because it evaluated various medial and aesthetics facets of music production. Melville Cooke’s paper “The Sound System and Radio: Establishment of Parallel Electronic Communication Networks in Jamaica” delved deep in assessing the relevance of sound systems as media in the context of post-independence Jamaica. Moreover, panel#8 Reggae Sound Systems From Around the World devoted large attention to the European scene of dub sound system and it was great for me to see the European scene being represented in such an important conference. The paper from Dimitri Corraze “The French Reggae/Dub Diaspora: Linguistic Practices and Identity Construction” made a nice conecptual pair with the paper David Bousquet’s “The French Sound System Boom in the 21st century, between Authenticity and Innovation” since both of them dealt with the delicate balance between tribute and appropriation, a very relevant topic in the context of a “global” reggae conference.

8 Mile sound system at Wicky Wacky beach

The rigour with which all participants presented their works proves that we can reflect on popular culture (such as reggae and dancehall) with the same seriousness with which we talk about supposedly “high” culture (classical music, experimental music). The dichotomy between high and low which, rather than celebrating the high part of the disjunction, hides the conceptual richness and vitality of what is considered low. The need to pay attention to these phenomena is not only dictated by the intellectual duty to form democratic knowledge, but also by the duty to celebrate the diversity of practices and the intrinsic value that they have for those who experience them. From this perspective, a good portion of philosophical reflection, disinterested in what was not part of the Western heritage, has always dismissed these phenomena as irrelevant, if not downright intrinsically harmful – certainly, not material for philosophers. The conference further stimulated me to contribute from my own research perspective so that all this richness that emerged and that I was able to feel and touch first-hand is valorized with the respect it is due. Because it’s never only music, but it’s also everything and everyone around it.

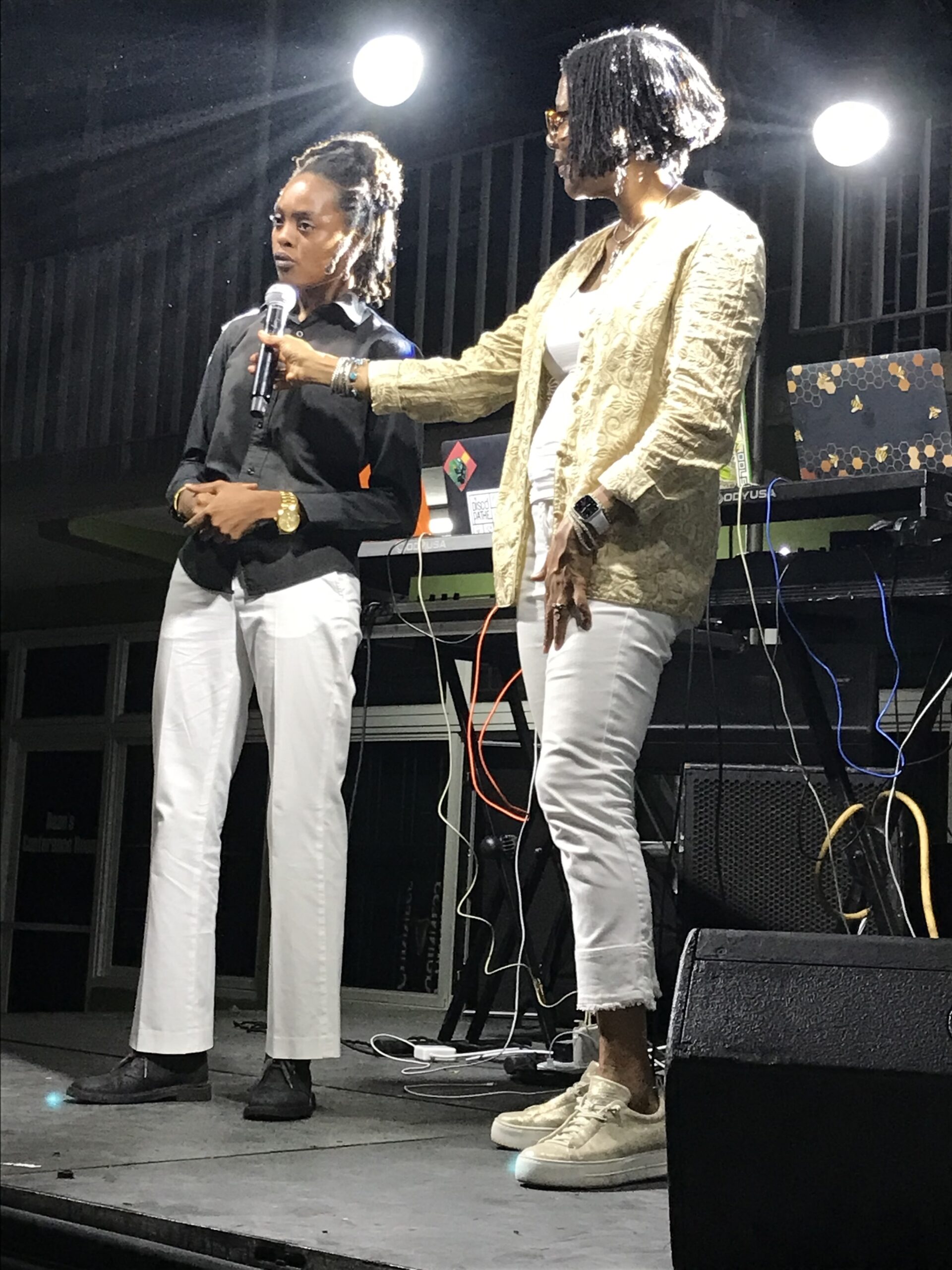

Guinness Sounds of Greatness student DJ J$ 200,000 prize winner DJ Kaotic (Alleyah Wright) (left) with Dr Sonjah Stanley Niaah

To conclude, I can only thank the entire UWI community, all the participants, the Caribbean and Reggae Studies Unit, all the technical staff, the entire SST research group and especially Brian and Julian for an experience that I don’t think I will ever forget and which definitely left me wanting to return.

All images by the author.

Giovanni Mugnaini is a Phd candidate in Aesthetics at the University of Bologna, Italy. He is riddim builder and selector for his sound system (Peaceful Warriors) and FOH and dubmaster for his band Afreak.