Book and exhibition review: Super Perry by Dennis Morris

The visual side of the popular music and sound system cultures has always been an interest of the SST project as able to capture subtle nuances and foster interrogations (see some previous blog posts here, here, and here). Best known for his iconic images of Bob Marley and the Sex Pistols, British photographer Dennis Morris has documented the durable impact of Jamaican popular music culture both on the island and abroad.

For today’s blog we welcome again SST friend and collaborator David Katz with a review of Morris’ latest book and exhibition entitled ‘Super Perry’, about no other than the visionary music producer, singer and performer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry.

by David Katz

By creating the Super Perry book and accompanying exhibition, photographer Dennis Morris has given us a special gift. The work offers insights on key moments of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s musical, spiritual and sartorial evolution, the best of which are the iconic images Morris shot with Perry at the Black Ark, the studio and sanctuary for the Rastafari faithful that Perry operated at his home on the western outskirts of Kingston for a handful of years in the 1970s. These evocative images underscore one of the most salient elements that have emerged from the ongoing research conducted for our Sonic Street Technologies and Sound System Outernational projects, which is that eyewitness accounts take precedence; without wishing to discount academic theory, which certainly has its place, both platforms have highlighted that lived experience can impart knowledge in ways that theoretical rhetoric cannot, emphasising that first-hand accounts are key to our understanding of specific moments in the emergence of sound system culture and the related dissemination of reggae on both sides of the Atlantic.

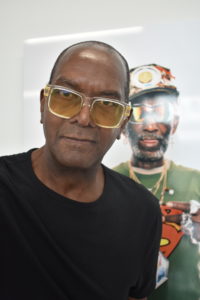

Photographer Dennis Morris. Image © David Katz

Morris was born in Jamaica and moved with his family to Hackney, east London, at four years old. He has recounted how, as a nine-year-old choirboy, he was captivated by the magic of photography after the vicar started up a camera club; one glace at a print being conjured in the darkroom, and Morris was hooked. He soon began photographing the local life of his community in Dalston, yielding marvellous images of sound systems such as Count Shelley’s, as well as the frightful extremes of the Black House, a squatted property in nearly Holloway Road presided over by the controversial activist Michael X, which was a sanctuary for underprivileged black youth but also gun-ridden and full of drugs. Morris once said that he was shy in his youth, but with a camera in his hands, he felt untouchable, which perhaps explains why he was able to thrive in such challenging spaces at a tender age.

Swimming against the tide and somewhat apart from his football-mad friends, Morris also faced societal prejudice, a career guidance counsellor notably suggesting that photography was not a viable career for a black working-class youth such as himself. But Morris would not waver and grasped the nettle instead: at the age of eleven, after stumbling upon a PLO demonstration, which he photographed, Morris sold his prints to an agency on Fleet Street, the work featuring on the front page of the Daily Mirror.

‘Super Perry’ book cover

Then, in May 1973, Bob Marley and the Wailers came to London to perform at the Speakeasy, an industry haunt north of Oxford Street; Morris, already a music head, wisely chose to bunk off school to attend the soundcheck, where he bonded with Bob, who offered encouragement as well as a permanent space in the van, thus allowing Morris access to himself and the band for the rest of the tour. The images that Morris shot with his Leica thus show an uncommon intimacy, being some of the few to capture Marley with an open grin on his face.

Morris has said that documenting the extremities of the local frontline of Sandringham Road was more important to him than photographing music acts, but after his Marley pics graced the covers of Melody Maker and Time Out, John Lydon requested his services when the Sex Pistols signed to Virgin in the spring of 1977, beginning another long friendship, which would result in more fine photographic work, as well as artistic design conceived by Morris, once the Pistols imploded and Public Image Limited entered their Metal Box phase.

But before all that, Dennis Morris made his first trips to Jamaica, some of the resultant work forming the bulk of the Super Perry book and exhibition. And although the hardback itself is on the slim side, containing just 42 images, the quality of the work and the care with which they have been reproduced makes it a worthy artefact for Arkologists everywhere. Dennis Morris returned to Jamaica in 1976, where he shot striking images of artists such as U Roy, Peter Tosh, the Gladiators, and other acts then signed to Virgin Records; rolling up at the Black Ark, he caught Lee Perry in relaxed mode, chilling out on the grounds with a grinning Junior Byles. Soft-focus portraits of Perry with a ‘soul’ hairstyle, tank-top and snaggle-tooth necklace have the feel of a bygone age and the black and white format furthers the air of nostalgia.

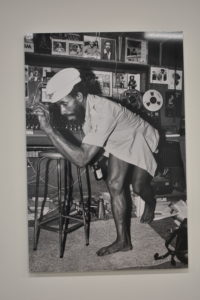

One of Morris’ iconic images of Lee Perry from the Super Perry London exhibition

There aren’t many surviving images of the Black Ark during its heyday, so these feel like privileged quarry. Yet, they are but a prelude to the further set of images Morris gleaned at the Ark when he returned in 1977, this time with Lydon in tow to sign acts to Frontline, Virgin’s reggae subsidiary. So now as Super Perry unfolds, we are treated to a series of images showing Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry very much in his element, dancing barefoot around the control room as a rhythm is laid, a Dragon stout and freshly rolled spliff to hand, in white shorts and a stylish top, looking creatively charged, gleeful, and fully in control at his Soundcraft mixing desk. The images convey a sense of the everyday nature of the scene, Perry immersed in his work and loving it, the conflicts with the Congos and Island Records not yet arisen, the atmosphere stimulating and burdenless. The potential punk-reggae crossover of the era is evident too in a shot showing Lydon and guitarist Earl ‘Chinna’ Smith sharing a moment of camaraderie, both with glints in their eyes, causing speculation on what might have been, should the creative juices managed to have aligned and flowed (which, according to Morris, was simply not the case in this instance).

The post-Ark chapters of Super Perry are in full colour, making the book and exhibition very much a ‘before and after’ project. Although there is a level of staging in the images of the Meltdown festival of 2003 and at the Jazz Café in 2016 that are not evident in the black and white Ark gems, Morris manages to maintain a sense of intimacy in these later London photo shoots. There are some tongue-in-cheek images of Perry standing on an open-topped London bus too, pontificating on cryptic subjects (before a sign that reads ‘no standing on upper deck,’ naturally), which were taken during work for a BBC Two television documentary, circa 2005; candid snaps showing a mirthful Perry sharing a joke with an equally mirthful Michael Rose of Black Uhuru are proof that Perry often managed to remain on good terms with those whose careers he helped to nurture decades earlier, despite the topsy-turvy times marked by the dramatic and often contradictory behaviour for which Perry became better known, once the Black Ark’s control room was destroyed by fire in the early 1980s, causing Perry to become a wondering nomad, in search of solace, and new means of self-expression, in distant lands.

Lee Perry’s Black Ark studio reproduction on display at the Super Perry exhibition, London 2022

As Super Perry was published by the Japanese Tang Deng company, the accompanying exhibition was first launched at Bookmarc in Tokyo. The London edition was housed on New Burlington Street in a beautiful gallery space with lots of natural light, which allowed the public to see large-format prints of this iconic work in optimal conditions. The day I went, Dennis was on hand to sign copies of the book and to offer his memories for all who wished to hear of them, and it was wonderful to hear some of the stories behind the images from Dennis himself. I learned that even in 1976, Junior Byles was already displaying signs of mental illness, and according to Morris, John Lydon never actually collaborated with Perry; he said the idea was to bring Lydon to the Black Ark to see whether he and Perry clicked, which they didn’t, so Perry and his musicians never even bothered to lay down any backing tracks for Lydon to voice, contrary to what has been written elsewhere. Morris was keen to emphasize that he and Perry maintained a friendship over the years that stretched beyond the boundaries of work; they maintained a bond and caught up at regular intervals.

Another bonus was the inclusion of a replica of the Black Ark’s control room at the exhibition, installed in an alcove on the side. There was a Teac four-track, a Teac two-track, and a Soundcraft mixing desk, as well as a Roland Space Echo, though it must be noted that the Soundcraft was a much later model to that used by Perry at the Ark, and even the Teacs were not verbatim replicas. Nevertheless, the installation gave a sense of the sparseness of the Ark, reminding of the wonders that Perry managed with such limited equipment.

Like the exhibition, which had a short run, the book has been printed in limited quantities, so those in the know will be wise to secure a copy now. Thank you Dennis Morris for giving us a new window into Scratch’s world.

—

David Katz is the author of People Funny Boy: The Genius of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae. He has produced documentaries for Public Radio International, including Ring the Alarm: A History of Sound System Culture and has hosted the monthly reggae vinyl night Dub Me Always since 2004. Visit him at www.davidkatzreggae.com