Beyond the Bassline: 500 Years of UK Black Music

SST is pleased to report on a ground-breaking exhibition at the British Library in London. In recent years Black music culture has received more curatorial attention than ever before. This exhibition is a welcome contribution to that trend. Though the show does not focus on sound systems in particular, it provides a uniquely valuable story of the long history of Black musicians and artists’ major contribution to British culture. SST collaborator Giovanni Mugnaini pays the exhibition a visit.

by Giovanni Mugnaini

In the last days of my stay in London, this period of study was further enriched by the possibility of visiting a beautifully curated exhibition dedicated to the history of Black music in England, in a rather peculiar context; the British Library. The British Library is one of London’s symbolic and most historical places; in fact, in the Treasures section of the British Library you can observe documents that embody the cultural and historical DNA of London and England: The Magna Carta, The Domesday Book, and an original copy of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Similarly, autograph scores by Mozart and Handel are displayed near the handwritten lyrics of Yesterday by the Beatles. The Treasures section unequivocally establishes a British cultural tradition and lineage in which however there is a glaring absence. What is striking is the absence of any reference to the contribution that has been given to the cultural and musical history of England by the Black population. This gap was brilliantly filled by the exhibition Beyond the Bassline 500 Years of Black Music. Dr Aleema Gray [1] is the lead curator in collaboration with Dr Mykaell Riley (University of Westminster). [2]

Exhibition Banner inside the British Library

The exhibition is located in the Paccar Gallery and will be open until 26th August 2024. It is certainly a must-see for anyone who is interested in the history of British Black Music. The closing date allows those attending the Notting Hill Carnival from abroad to pay a visit. The exhibition has the fully realized ambition of representing and making perceptible to visitors the breadth and depth of the influence of Black music in England. The title of the exhibition may sound hyperbolic, 500 years, but once you go through it you discover that it is not the case. This exhibition represents a milestone in the recognition of the Black component of British musical history.

A Notting Hill Carnival Costume

At first glance you might think that this influence is limited to the early 1900s with the arrival of Black music genres such as jazz, swing and blues. Indeed, the true value of the exhibition lies precisely in this. On the one hand, it obviously pays homage to the contemporary and most established forms of Black music such as reggae, jazz, grime, garage and jungle, that have influenced not only the British musical panorama but also the world music scene. On the other hand, thanks to the expert archival work, stories it also roots out and displays a stream of histories that otherwise would remain unacknowledged. The various sections and stories tell of Black music’s relationships with British history and the social and human challenges to which it responds.

Black Chronologies

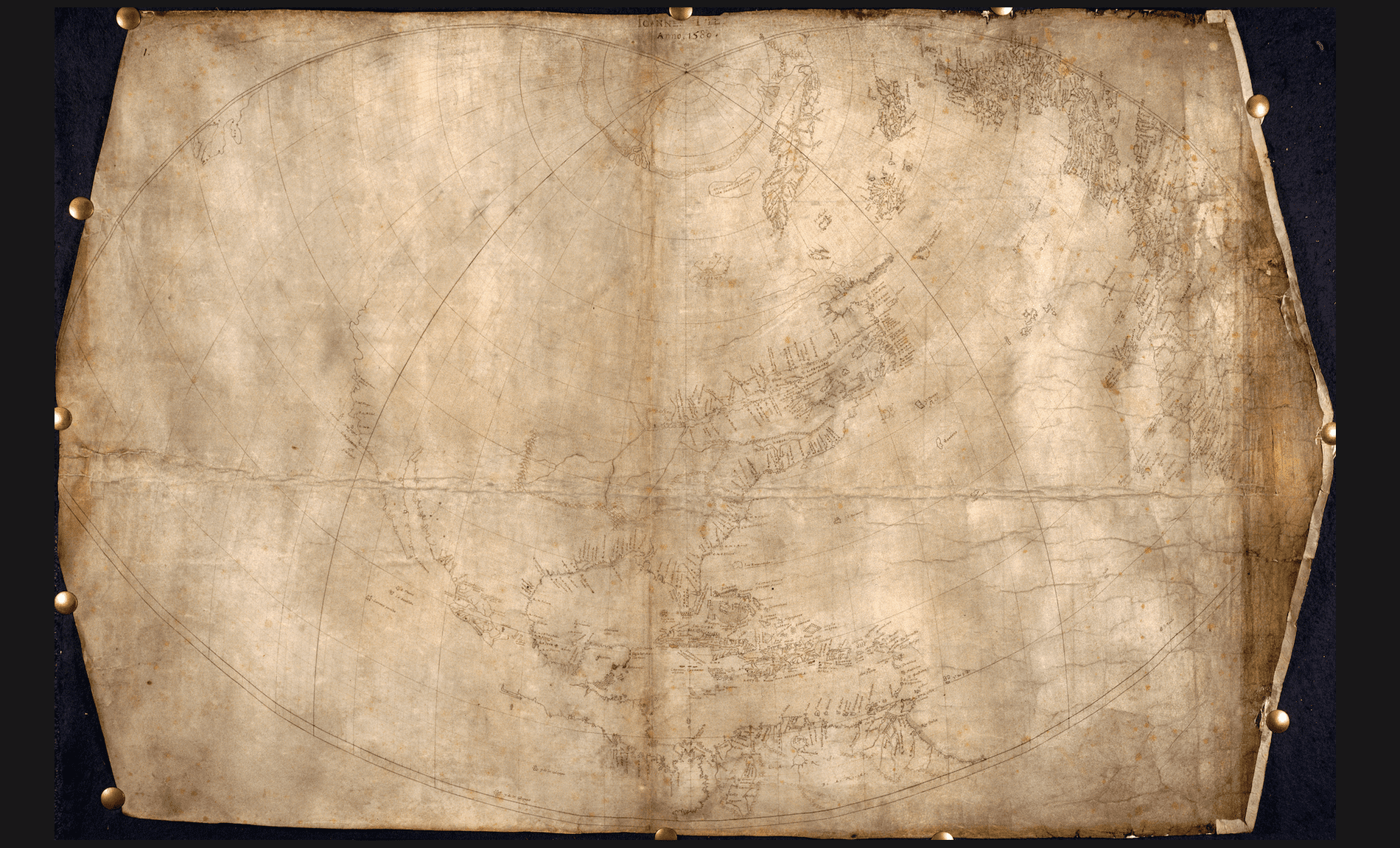

Beyond the Bassline divides its story into five sections arranged chronologically. After each section there is an “interruption” – namely audio, image or video installation – curated by different collectives from all over UK as testimony of their active contribution to British culture. The exhibition opens with the Ocean section, dedicated to the years 1500-1870 and stories of diaspora and forced deportation; stories of musical practices and embodied cultural forms that deported slaves brought with them. In this section, spatially and atmospherically characterized by blue curtains and marine sounds, visitors will be able to learn the stories of George Bridgetower, renowned Black English composer, and John Blanke, musician at the court of Henry VIII, famous for requesting an increase in his daily wages from 8 to 16 pence. As Mykaell Riley told us, the discovery of the “Letter of Favour” with which the King granted John his salary raise allows historians to factually prove this story. The first items presented in the exhibition is John Dee’s world map commissioned by Queen Elizabeth 1st in 1580. This was the first time the term “Empire” was used to refer to the overseas land conquered by the British crown.

Map of America by John Dee, 1580

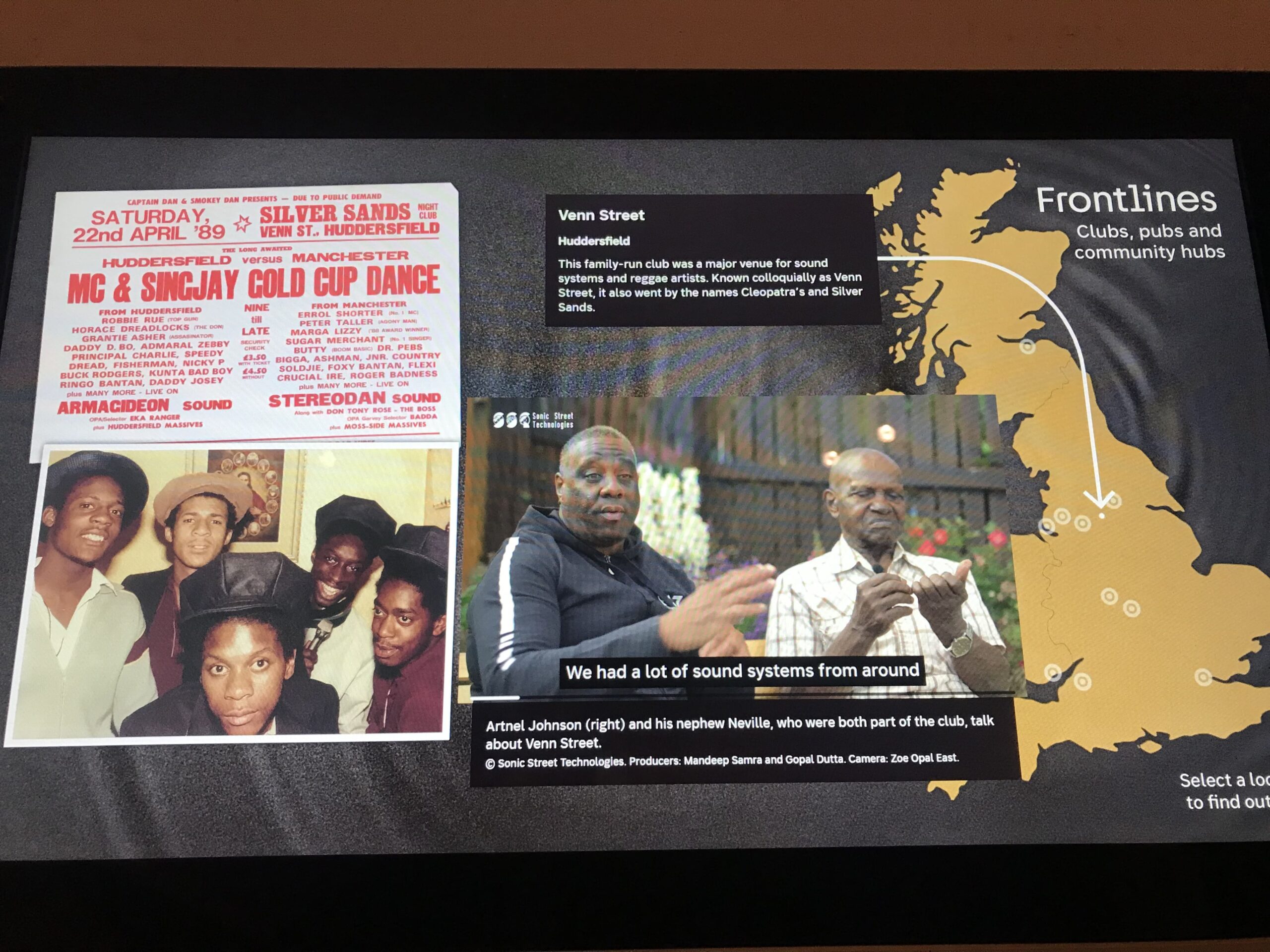

Immediately afterwards the On Stage section honors the undeniable influence that Black musicians had on the period from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. The early 20th century were the years in which Black creativity exploded and the weight and skills of Black musicians led them to shine as stars in the jazz and swing era. However, the section that interested me the most was On the Frontlines as it aligned with my research and with the SST project. In fact, for fans or researchers interested in sound system culture or reggae studies these sections contain some artifacts whose charm and importance would be impossible to underestimate. On the Frontlines recalls the emergence of the various clubs as safe places where Black people oppressed by the racism in the the society at large, could find shelter and express themselves freely. There you can also find an interactive map with a contribution from the SST project showing a video interview on the reggae history of Huddersfield, see the SST YouTube channel. Huddersfield in Yorkshire in the north-east of England was a vital center of English sound system culture in the 1980s.

SST project’s contribution to the exhibition, the interactive map of English clubs

For me, the another really striking section was In the Record Shop. This houses perhaps the flagship artefact of the exhibition, a King Tubby’s Home Town Hi fi scoop bin, one of the few in existence. The fascination that it arouses in anyone who is somewhat familiar with sound system culture is undeniable. In fact, it represents the instrumental archeology of a practice that has evolved and continues to differentiate itself and emerge in different forms but which has its own historical roost in Jamaica. Personally, admiring the bass scoop belonging to Tubby’s gave the exact same sensation as seeing any historical artefact contained in one of the many London museums. This is the sensation of having before your eyes a technological object that marked the incipit of practices and ways of appreciating and sharing music that have the same dignity as a Vivaldi’s violin or Beethoven’s tuning fork.

King Tubby’s bass bin

Whether clubs, carnivals or the uprisings that characterized the 1970s and 80s, the testimonies and stories told give the measure of how much the music and the spaces involved were literally frontlines – battle lines against “Babylon.” In addition, to wonderful costumes for the carnival, in this first section you can see an original preamp that belonged to “The mighty Ruler”, material testimony to the inventiveness and non-standard creativity that has always characterized these musical practices.

The Mighty Ruler’s Preamp. As Mykaell Riley told us the lights on the preamp were generally the only lights in the dancehall, focusing dancer’s attention to the music

Alongside Beethoven’s tuning fork, we find Dennis Bovell’s guitar and in wonderful displays the records that have marked the history of Reggae and its various subgenres. The two sections also highlight the DIY culture as an integral and structuring part of the non-standardized ethos of production proper of sound system culture whose technological innovations have been a key feature. Finally, the Cyberspace section closes the historical journey and, by telling the story of grime, jungle and the Mobo awards, opens up the continuation of the story that is told by the exhibition as a whole; a story that is still evolving and shows no signs of stopping.

The final section of the exhibition is occupied by a fantastic immersive 5-channel audio installation entitled Iwoyi, directed and created by Tayo Rapoport and Rohan Ayinde alongside Errol and Alex Rita’s Touching Bass and with a soundtrack made by Melo-Zed. Iwoyi is a multimedia story that succeeds in expressing the overall feel of the exhibition. Many of the topics and themes of the galaxy of Black music and Black studies scholarship are portrayed: the heritage, the diaspora, the sonorities and the intimate creativity animating Black music culture. Iwoyi is projected on walls and ceiling, surround sound and a super-heavy subwoofer providing a stimulating musical and visual experience with which to leave the exhibition.

A Garrard 4HF turntable favoured by the late Jah Shaka and other reggae pioneers

Museumification

Diaspora memory is often embodied memory, as the late Benjamin Zephaniah used to sing “Our story are in our songs.” It is a memory that is orallypassed and which materializes from time to time in those who incorporate and perform it. The relevance and importance of exhibition such as this cannot be then underplayed. By recollecting all the materials and archival items and accompanying them with video testimonies, the exhibition conveys this dual level of incorporation and externalization brilliantly.

In my view, Beyond the Bassline shows how an exhibition can depict a living culture in an appropriate and lively manner. The exhibition testifies a broader shift in the cultural discourse long overdue. One could argue that an exhibition of this kind serves to represent the past in a sanitized manner, thereby defusing its most subversive aspects and rendering it harmless. But this is not the case; in fact, the very transience of the exhibition serves a dual purpose. On one hand it is not something definitive permenantly on display. On the other, it assesses musical cultures as living organisms that keep on working, evolving and contributing to British and global musical history.

If anyone should doubt this assertion, one can easily visit the Notting Hill Carnival (on 24th to 26th August) after the exhibition to experience the liveliness of the cultures represented in Beyond the Bassline. As Mikaell Riley says:

The music celebrated in this exhibition is more than a collection of sounds. It’s a living history, echoing through the centuries […]. The aim was to challenge the very idea of Black British music and its relationship to British history […] Ultimately, the exhibition is expected to both electrify and provoke, but most importantly, to energise and inspire continued exploration into this essential facet of British cultural heritage.” [3]

Alongside the artifacts and documents, there are always videos and audio materials that allow you to completely immerse yourself in the story of the exhibition. The brilliant curatorial work of Dr Aleema Gray makes it a living, multimedia, atmospheric exhibition. The feeling is not that of walking through an archival space, but rather of experiencing the vitality of this musical history. We are constantly transported through different eras and atmospheres conveying the feel and texture of both the cultural context and the actual music.

Notes

[1] Dr Aleema Gray is Jamaican-born curator, researcher and public historian based in London, currently at the British Library. She was awarded the Yesu Persaud Scholarship for her PhD entitled Bun Babylon; A Community-engaged History of Rastafari in a Britain. Aleema’s work focuses on documenting Black history in Britain through the perspective of lived experiences.

[2] He is a Senior Lecturer, Director for The Black Music Research Unit (BMRU) and Principal Investigator for of the AHRC funded Bass Culture project. Mykaell’s career started as a founder member of the British roots Reggae band Steel Pulse .

References

[1] Mykaell Riley, Beyond the Bassline: 500 years of Black British Music,London: British Library, 2024. pp. 21-24.

About the author:

Giovanni Mugnaini is a Phd candidate in Aesthetics at the University of Bologna, Italy. He is riddim builder and selector for his sound system (Peaceful Warriors) and FOH and dubmaster for his band Afreak.