Musical Youth Pt. 2: A Struggles Music

This week’s blog continues the series on the intergenerational dimension of sound system culture in the UK by guest author Becca Leathlean. After writing on her own journey in reggae, from being a solitary record collector to selectress and broadcaster in this previous blog, it’s now the turn of the older generation to give their perspective on the current state of the culture in the UK, specifically London. This second instalment also considers the importance of Rastafari for the development of roots reggae and dub music in the UK.

by Becca Leathlean

“Sometimes when I was dancing, I would close my eyes and it was like I had gone back somewhere. The music seemed to link me back, generation through generation. I felt like myself, not who the system told me I was. I felt like the real me.”

(Lady Issachar)

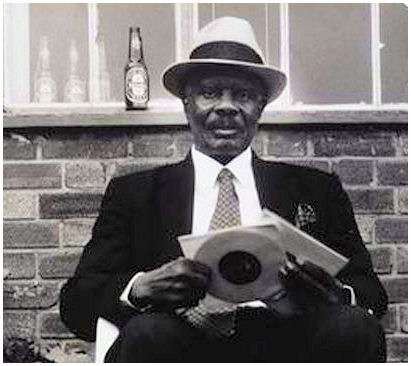

UK sound system pioneer Duke Vin (source: web)

The First Sound Systems

Sound systems were born in Jamaica after WW2, originally wired up outside record shops to drum up trade. With glowing valve amps, huge speakers and a deck, they played ‘blues’ music – early R&B, jazz and soul from artists like Sam Cooke, Nat King Cole, Louis Jordan and Fats Domino.

The first UK sound systems were started by Duke Vin and his soon-to-be rival Count Suckle, who arrived in England as stowaways in 1954. Performing mainly at blues parties, so named after the music and held in the homes of newly arrived Caribbean families, the parties were a lifeline for Black people hit not only by discrimination in housing and employment, but made unwelcome in public clubs and commercial spaces. Soon, music-lovers from all kinds of backgrounds were attending, and sound systems started to play in public venues, too.

Reggae Sound Systems as a Refuge

Born in the 60s, many second-generation African-Caribbean children grew up to the sound of Studio One and Treasure Isle at home, but life outside was far less pleasant. The first generation to go to school in the UK faced racism from the start.

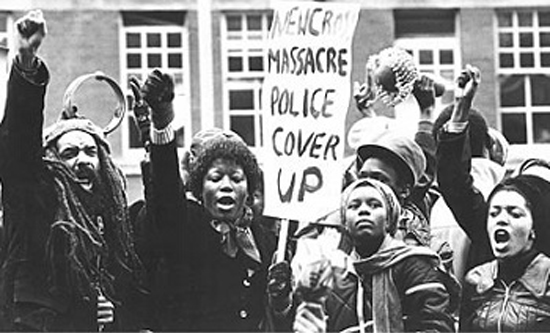

Education, the fifth in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series, is a heartbreaking indictment of racism in primary schools where Black children were routinely written off as educationally subnormal; while the ‘sus law’, brought in during the early 1970s, saw Black youths as young as 12 routinely arrested for activities as innocent as waiting for a bus or looking in a shop window. [1] Black males were stereotyped as muggers in the media, [2] while attacks on the Black community often went un-investigated and unreported. Following the New Cross Fire in January 1981 where thirteen Black youngsters lost their lives, people on the Black People’s Day of Action march to protest about police inaction and unsympathetic media coverage of the tragedy were taunted with racist chants and spat on. In April 1981, the Metropolitan Police conducted its notorious Swamp 81 operation in Brixton. Over two days, 1000 people were stopped and searched and 150 arrested. It was the last straw for the Brixton community and resulted in the first Brixton uprising a few days later, followed by more unrest in cities around the UK that summer. [1]

Black People’s Day of Action, 2nd of March 1981 (source: web)

There was repression in Jamaica, too. Even as Bob Marley was becoming a revered global icon, Rastafarians in Jamaica were still being treated like second class citizens. In her memoir, How to Say Babylon, Safiya Sinclair recounts the experiences of the Rastafarian community since the movement’s inception in the early 30s until the late 60s: “They [Rastafarians] were the nation’s black sheep, feared and despised by a Christian society still under British rule, forced to live on the fringes as pariahs. They were the involuntarily landless and homeless, their encampments sacked, their fields burned by the government in service to the Crown. They were the unemployed and unemployable, the constant victims of state violence and brutality, the ones the government jailed and forcibly shaved, the ones brutally beaten by the police.” By the 1980s when Sinclair was born, although there was less violence, Rastafarian families such as her own continued to be stigmatised and ostracised. [3]

Yet, crucially, out of the suffering have come Roots Reggae and Dub, two of the most beautiful, inventive and enduring musical forms ever; and for Black youths in 1970s UK, a new generation of sound systems would come to the rescue. Many of the young people were drawn towards Rastafari.

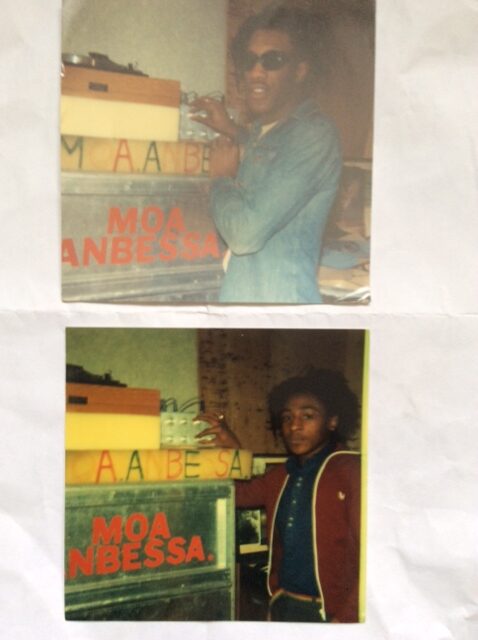

Man fi Bill (top) and Gary were two founder members of Moa Anbessa International, the UK’s first Rastafarian sound system

Rastafari in the UK

Man fi Bill is one of six founder members of Moa Anbessa International, the UK’s first Rastafarian Roots Reggae Sound System, launched in 1977. The crew had come up through Lord David Hi fi Sound. “We could see a lot of our brothers and sisters were consciously lost at the time,” he says.

“We were struggling to identify with the Greco Roman philosophy we were brought up with; Catholicism and Christianity. We weren’t into the European history – we were getting more and more influenced by Marcus Garvey and the Rastafari Afrocentric way of life. So we decided to talk about the positive influence it was having on us and the music scene in Jamaica and the UK at the time.

“We painted our speakers red, gold and green, which are the colours of the Ethiopian flag, and played music by artists like Burning Spear, Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Culture, Mighty Diamonds, Gregory Isaacs and Yabby You. There were just so many amazing recording artists. We found that when we played cultural music promoting Black liberation, Black history, Back to Africa and the positive mindset of people coming together, the audience was growing astronomically.”

Lady Issachar (image courtesy of Helen Maria Williams)

A vinyl DJ since 2019, Lady Issachar started going to sound system dances aged 16, around the same time.

“At school, a lot of the children didn’t like us. We’d have to fight and we got into trouble. Even at work when I grew up, the white girls were not very nice. But whatever you went through during the day, when you went to a dance it felt just right. It was wonderful to get away and listen to what fulfilled us – Dennis Brown, Bob Marley and Black Uhuru. When I went to the dances and I heard dub I was like, ‘Dub, Yes! Roots music, Yes! Lyrics, Yes!’ The harmonies and melodies went to my core.

“I remember standing in dances round Rasta people chanting out the lyrics and believing in what was being said about Haile Selassie, God, the way of life. Living off the land, being at peace with people. Everything that came through the music was everything I felt. I wanted to be part of that good culture because I couldn’t see any goodness in the world.If you see a light, you go towards that light – it was like that.”

An Independent Economy

Not only did 70s sound systems offer a refuge for their audiences, they provided work, creative fulfilment and business opportunities for their operators, in the main young Black men facing discrimination in the conventional job market. Soon, people were setting up as vinyl importers, gig promotors and record vendors in specialist shops such as Peckings, the first London outlet to bring records direct from Jamaica in 1974, and Dub Vendor which was born in 1976.

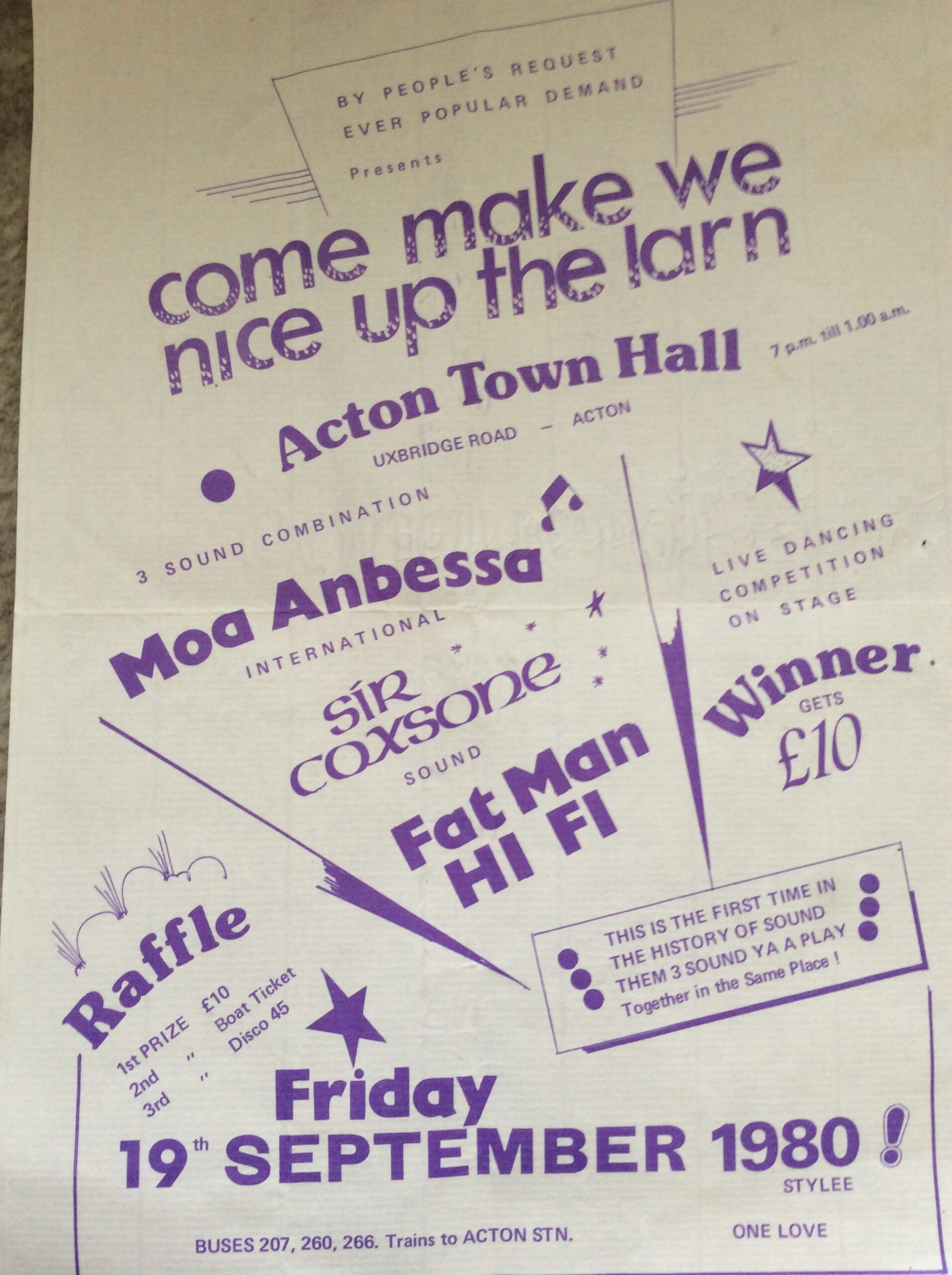

1980 poster for a three sounds dance including Moa Anbessa, Fat Man Hi Fi and Sir Coxsone

A number of UK reggae bands formed, too, such as Matumbi, Misty in Roots, Steel Pulse and Aswad, while British Lover’s Rock artists such as Janet Kay MBE and Carroll Thompson found great success. For some, the music business offered social mobility and an escape.

Moa Anbessa International was one of many UK reggae sound systems during the 70s and early 80s, often performing on the same bill as other top names such as Sir Coxsone, Sufferer, Soferno B, Mafia Tone and Fatman Hi-Fi; but Jah Shaka was one of just a handful to continueafter the introduction of Dancehall in the mid-80s and digital music forms in the 90s which seemed to eclipse Roots and Culture music. “

“A Shaka gig was like nothing else on earth,” says Goldsmiths College press officer Patrick Edwards, who attended in the 90s. “It was like cathedrals of sound, complete audio awesomeness, sometimes coming from the most mundane venues.”

Jah Shaka events were renowned for attracting a wide audience from all backgrounds, races and ages. “It was like the United Nations of Benetton. The first time I saw a Sikh in a dance was at a Shaka gig,” reminisces fellow sound system owner, Sista Culcha, who also kept her Roots and Culture operation going through the 90s and 2010s.

The Return of Roots and Culture Clubs

Gentrification dealt a blow to Black cultural life in the early 2000s as, in areas such as Lewisham in London, community centres were cleared to make way for apartment blocks for new middle-class arrivals. Even worse, the Metropolitan Police’s 2005 Promotion Event Risk Assessment Form 696, required of club promotors hosting musical events featuring ‘DJs and MCs’, had the effect of clamping down on Black music in the capital altogether. [4] The form was scrapped in 2017 and, after a hiatus of almost 30 years, a new generation of Roots and Culture club nights was born.

“In 2018 I got a call from Softwax Steve,” recalls Man fi Bill. “He invited us to play at his new night, the Deptford Dub Club. It was a really great occasion. Then David Katz invited us to play at the Ritzy in 2019 and we got various other calls to play our vinyls and dubs.”

The new audiences were somewhat different to the old, with the Deptford crowd now including overseas visitors, Goldsmiths students and dancers from the nearby Laban Centre.

“There were a few audience members we’d grown up with and the rest I’d never seen before in my life!” laughs Man fi Bill. “I think it’s good to have this multicultural crowd of people who really dig reggae and appreciate it to the extent that they’re fanatical.”

Deptford Dub Club at the Duke, circa 2016 (source: DDC)

Today’s reggae fans are younger and more diverse than they’ve ever been, coming to Roots music via a range of sources such as their parents’ records, reggae samples in Jungle or D&B or having been to a sound system like Shaka or Channel One. A new generation of young reggae selectors and sound systems has sprung up in tandem, with far more women and non-binary people on board than before. The opening up of the scene has brought opportunities to older womxn*, too, like Lady Issachar and myself. [5]

Worries in the Dance…

But not everyone is well disposed to the involvement of the ‘hipster’ generation, fearing a dilution of the Roots Reggae genre and expressing concerns about the lack of young Black people on the scene [6]. And, while they accept that the music must evolve, some sound system elders are sceptical about the youths’ ability to preserve its legacy, fearful that if they don’t understand and acknowledge the history and struggles that forged the music, all could be lost.

“It’s so important for young people to have a grasp on the music and where it originates if they want to go into the industry in any capacity,” says Man fi Bill.

“If you don’t know where you’re coming from, it’s hard to know where you’re going. If you take the root from the tree, it will topple over. You can’t throw away the root, but I think a lot of the young people are throwing away the culture and history, and taking up new musical forms that have no substance. They may get away with it short term, but they’re not on a solid foundation.

“My opinion of the new music is that some is good, and some is very disposable. Are we going to be playing this stuff in 50 years’ time, like we’re still playing music from the 60s and 70s? It seems like these days everyone is copying Shaka – that’s what reggae is to them. They constantly want the Shaka sound or Steppas. [7]

“What bores me is when there’s no variation. Moa Anbessa used to talk about the messages in the music, but we’d play a whole mixture, including, vocals, instrumentals, toasting and dub; even Lovers Rock.

“I don’t have a problem with the new digital equipment, I just don’t think you get the true sound from it. With the original valve-driven amps you got that really warm, bouncy, inviting sound. And there’s nothing like the crisp, clear sound of a tannoy for the top and middle speaker sections. Dialogue, clarity and content are very important.”

For Sista Culcha (aka Donna Halley-Moore) who ran the all-woman sound system of the same name from 1983 to around 2013, a proper archive would be the answer.

Sista Culcha came up through the 80s feminist and spoken word/poetry circles, bringing them reggae, soca and R&B. Like Lady Issachar, Donna came from a musical family, and cites Motown and Bob and Marcia as early influences.

Sista Culcha selecting

“As a DJ, I’d play whatever resonated with me. I like a mixture of a message, a melody and good musical composition. Culture’s Two Sevens Clash is a great example of all three, you can’t fault it. It’s giving you history, too, and you know when something embodies a lot of your passions? Reggae music does that for me more than any other music.”

Sista Culcha is more optimistic than Man fi Bill about the younger generation’s ability to preserve the legacy of sound system.

“I met some of them for the first time in 2013, at a conference for different generations of sound system women,” she says.

“I was so enamoured of these young women who were equally enamoured of us female pioneers! It’s really lovely to see young people like B.O.S.S. who are building their own boxes and CAYA who’s taking it to another level with her microphone. These are educated women – they have their degrees and careers. I’ve been so impressed to see how they approach things and I’m really happy they’re in that space and taking things forward. Because we couldn’t have carried on forever and we need help to keep this music relevant and keep it alive. And once that generation of women grows up, others can follow because they are so relatable.”

Sista Culcha’s answer would be to preserve the history of reggae – struggles, stories and all – in an interactive out-of-town archive at least as big as Detroit’s Motown Museum, somewhere people could go for extended visits to immerse themselves in reggae/sound system culture – listen to music (she herself has 10,000 records to find a home for), watch films, research, view old ephemera and tuck into Caribbean cuisine. “Now that reggae has been recognised by UNESCO, it’s a music that undeniably cannot be ignored,” she says. [8]

A Reggae Museum in London

So, it was amazing to discover, in the last days of writing this article, that just such a museum could already be on its way, destined for premises in Brent subject to getting Lottery funding.

The brainchild of musical entrepreneur Colin Robinson, the Reggae Museum has been several years in planning, preceded by a series of well-received exhibitions. The museum will feature reggae music artefacts, memorabilia and collections focusing on those who have contributed to the advent, growth and worldwide influence of the genre. It will take visitors on an exploration of the very roots of reggae music and how it has developed.

The Reggae Museum logo

“We have to preserve the culture,” says Colin, who was waiting to hear whether he would be gifted the dress worn by Millie Small on Top of the Pops when we spoke. He’s already collected over 1000 artefacts including Bob Marley’s Fender guitar, a Trojan mixing desk, 200 rare records, two Blue Spot Grams**, hundreds of photographs, three sound systems (one complete with an 8-valve amp and tannoy speakers) and billboard posters for The Wailers’ Catch a Fire album.

Colin’s vision is for a multimedia exhibition space, comprising not just the artefacts but films, a radio station, traditional Caribbean food, cookery classes, song-writing/music workshops, music publishing and an outreach team visiting hospitals and prisons. He’d also like funding for more research.

The team has been offered a disused library for six months to monitor footfall, prior to hopefully being granted land or a building in Brent.

Such an initiative is clearly long overdue and would be of immense value, instilling pride in, and recognition of reggae’s social history and contribution to British music and culture. It could also go some way to acknowledging the trauma faced by Black people growing up in the UK during the 50s, 60s and 70s’.

“Talking to you now, I’m trembling,” said Lady Issachar when we spoke about a police raid on a party she had been at in her 20s. “It brought back how scared I was. And the New Cross Fire is as clear in my mind as yesterday. We still don’t know the truth. So, even now, if I feel a way, I shut my door and put on the music I listened to 50 years ago. In my mind, I create it again, that safe space.”

Known especially for playing roots and dub, Lady Issachar often pays tribute to her forebears with earlier selections.

“When I play Studio One, it’s in memory of my dad and my uncle – two strong men in my life. They were the record player masters – without them, I wouldn’t know anything about it. They gave it to us, and they got it from someone, who got it from someone else. The music has been brought down the line to us from Africa. It tells us who we are.”

NOTE: It’s been fascinating putting this article together. Number 3 in the series will explore the views of young selectors and sound systems operators coming onto the scene.

—

Becca Leathlean is a writer and teacher with a long-term love of roots reggae. She returned to London in July 2022 to take up opportunities as a vinyl DJ and to present a world-reggae radio show.

NOTES & REFERENCES

[1] See, for example, Steve Rose’s profile of social justice campaigner Mavis Best in The Guardian on 2 December 2022

[2] Hall, S, et al. (1978) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order

[3] Sinclair, S (2023). How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir. Sinclair goes on to write about an incident in 1963 when, after they refused to relinquish the farmlands they lived on to the Government, Alexander Bustamante, the white prime minster at the time ordered the military to ‘Bring in all Rastas, dead or alive!’ This triggered a murderous military operation, usually known as the Coral Gardens massacre, where Rasta communes across the island were burned to the ground and more than 150 Rastas were taken from their homes, beaten and tortured, and an unknown number were killed. In April 2017, following a legal investigation, the government of Jamaica issued an official apology, and condemned its own actions in the incident. It also established a trust fund to aid survivors harmed in the incident. https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/news/20170404/government-says-sorry-1963-coral-gardens-massacre

[4] Hyacinth, N (2023) for Sonic Street Technologies. The Sound of Lewisham from the 1950s to Now

[5] See for example, https://thevinylfactory.com/features/vinyl-sisters-interview/

[6] The lack of young Black sound system operators was an issue raised at SSO#8

[7] For a definition of Steppas music, see for example: https://pianity.com/tag/stepper

[8] Reggae music was inscribed in the 2018 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural History of Humanity. See https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/reggae-music-of-jamaica-01398

* ‘Womxn’ is a term used to be inclusive of trans and non-binary women.

** A Blue Spot radiogram was considered the best by the Caribbean community who moved to the UK in the 1950s and was capable of receiving a radio signal from Jamaica as well as playing vinyl. See, for example: https://museum-collection.hackney.gov.uk/object-2010-90

See also the Instagram feed of King Earthquake, who has recreated a 1950s front room in his home and broadcasts a regular radio show: https://www.instagram.com/p/CztzmywsK4b/?hl=en