56th Anniversary of La Merced. A Soundwalk in Mexico City pt.2

The SST project is keen to document the impact that the pandemic had on the activity of sonic street technologies worldwide, in both bad and good ways. The ban on sessions and the increased police repression are among the most common negative outcomes experienced by all SST scenes at different latitudes. Young researcher Linette Rivera returned to the streets of Mexico City to verify the impact of Covid-19 restrictions on the traditional sonidero celebrations of La Virgin de la Merced.

This blog is also available in Spanish at this link

—

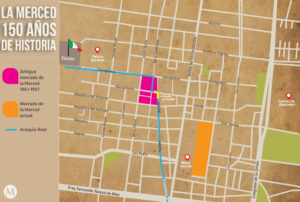

Old market area of la Merced in pink and current one in orange.

La Merced is one of the oldest barrios in Mexico City. Teopan was the name given to the calpulli or barrio during the pre-Hispanic period. Within the barrio, there is Plaza de La Aguilita, an iconic site. Currently in the site there is a sculpture that represents the myth of the Mexicas, where an eagle was found devouring a snake on a nopal, marking the foundation of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. During the colonial period the barrio was dedicated to the Virgin of La Merced, thanks to the religious order of the Mercedarians. In 1593 the Mercedarians founded a small convent and in 1603 they began the construction of the temple of Nuestra Señora de La Merced.

La Meche, as it is also known, has been engaged in trade since ancient times. The Merced area has more than a thousand stalls and shops that supply Mexico City with a variety of food coming from all over the country. Every September 24th the market vendors organise a great celebration of the Virgin and the sonideros install their equipment on the surrounding streets.

Local authorities patrolling the streets.

Years ago, the celebration attracted renowned sonideros from Mexico City as well as neighbouring states such as the State of Mexico, Veracruz, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Guerrero, and Hidalgo [1]. A few years ago, local authorities banned music and dance from the area due to acts of violence generated during the festivities. Besides that, the huge street dances held on Circunvalación Avenue cause severe traffic disruption due to the area’s proximity to the city centre. In 2021, the police operations in the area began on the night of September 23rd to prevent the installation of sound equipment and the gathering of crowds due to Covid-19 restrictions. Aware of that, some sonideros smuggled part of their equipment into the market the night before. One particular sonidero accessed the area hiding part of his equipment in fruit boxes to pass the police checkpoints [2]. One of the tenants and organiser of the celebration in La Merced, named la Güera, was beaten by the police a night before for placing an altar to the virgin, tables, and chairs. Police did it in order to avoid the sonidero equipment to be installed in the parking lot [3].

An altar dedicated to the Virgin of La Merced.

A day after attending the celebration in the Sonora market, I was interested in touring La Merced. I met with Luis, my former classmate (see previous blog) on Fray Servando Avenue and we headed to the main warehouse of the market. We saw a first altar on the street corner, where we dodged a table full of diners who enjoyed their meal. The main hall was full of stalls. Some vendors had set up altars and tables to celebrate the Virgin with food. Also, some of these altars had small sounds enlivening the occasion, but it seemed to be private celebrations.

Cargo trucks occupying the Northern parking lot, an important dancehall spot, to avoid sonideros to setup.

During the visit Luis showed me some of the streets where the Sonidero used to settle. We realized that these public spaces, the most representative for sonideros in La Merced, were blocked with patrols or cargo trucks. On Circunvalación Avenue, a police checkpoint was in place until the afternoon to prevent the sonideros from settling. As we toured the area he described to me the magnitude of the celebration years ago in the area. Fausto Perea of Sonido Eckos, one of the most representative young sonideros of Mexico City, later explained to me that what I could see that day was just a small percentage of a real sonidero celebration of La Merced. He also added that La Merced was a sort of Sonidero showcase: ‘many sounds attended because they wanted to participate in this celebration’ [4].

A couple dancing among the market stalls, where the sonider was hidden.

Nonetheless, we managed to witness a few dances. There were people, unlikely to be buyers, walking among the streets looking for a dance just like we did. We were able to spot the sonideros among the market crowd because of the traditional rueda that is formed in the dances. The sonideros played among the stalls to avoid being discovered and their equipment confiscated.

Sonideros merchandise such as stickers, cassettes and a calendar.

Close to the North parking lot, in front of another altar dedicated to the Virgin de la Merced, there was a comal where tacos were prepared for the people who gathered. Some vendors usually offer food. A police motorcycle patrolled the area to ensure that no sonideros were installed. In the middle of the street there were some stalls selling sonidero merchandise, such as stickers, sweatshirts, caps, t-shirts, and session recordings on cassettes. In one of the stalls, I was also surprised to see a lot of sonideros logos printed on a Virgin calendar.

Concheros ritual dance.

On one side of the church of Santo Tomás de la Palma, the sound of huehuetls [5] and snails rumbled on the walls of the street. In addition, the smoke of the copal [6] was immediately perceived, giving that special and distinctive touch to the traditional dances of concheros. The concheros perform their dances to the sound of musical instruments of pre-Hispanic and colonial origin. An altar dedicated to the four cardinal points is placed while asking for permission and protection before starting the dances. The characteristic costumes they wear are self-made, embroidered and/or decorated. Every year, groups of dancers come from different cities to join the festivity. The street had been closed with a metal hurdle to prevent people from crowding. I approached a huge altar, decorated with floral arrangements. Some merchants received sahumation [7] with copal incense, and swept with bunches of energy-cleansing herbs. Meanwhile, the concheros dressed in their colorful clothes were preparing to perform another dance.

Police occupying a renowned sonidero spot

When we retired from the shell dance we noticed another of the main sonidero spots blocked by a patrol parked in the middle of the street. Meanwhile, several attendees were having drinks in the street waiting for a sonidero to show up.

Attendants dancing on the street

We turned to general Anay street. The access seemed difficult for the police as it was crowded with people and stalls that were still working. A few minutes later we bumped into a crowd waiting to dance, as the music had just stopped. As we waited for the music to start again, the bustle of the people was one of rejoicing. The chatting, the laughter and the cackles that were heard during the wait, gave another touch to the party, as it is usually very difficult to hear what people are saying when the music plays.

This session was more crowded than previous ones. After few minutes, the music was playing again, and people started to dance.

Fausto Perea of Sonido Eckos

On the same street, a few meters ahead we met another crowd. Some couples danced in the rueda. Sonido Eckos enlivened the festivity in front of an altar, its perimeter delimited to prevent the passage. As I approached to take pictures, a young woman invited me in. Friends and family enjoyed the moment, as I moved closer to the altar I dodged huge saucepans placed on the floor, almost empty of the food they offered. Fausto Perea – Sonido Eckos, is one of the most representative young sonideros of Mexico City. He belongs to the Perea family, which has a great sonidero legacy. The Perea family is originally from one of the sonidero cradles of Mexico City, El Peñón de los Baños or La Colombia Chiquita as it is also known, close to the international airport of Mexico City. The Peñón de los Baños is another of the original neighbourhoods of Mexico City home to an Easter Carnival celebration very popular among sonideros.

An important sonidero spot which used to be crowded a few years ago

In addition to the ban on dances due to the violence that has arisen in previous years, on this occasion, local media announced the cancellation of festivities of any kind due to the pandemic. As a result, many people did not attend the festivity of the market as usual. However, the Covid-19 restrictions were not an obstacle for some sonideros, merchants and punters waiting to celebrate La Virgen de la Merced with a proper session. People were happy to meet again after a long lockdown and to have a good time. The next day in the media there was no mention of acts of violence as was the case in previous years.

—

Linette Rivera is a student of Linguistics at the National School of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. She is interested in sound system cultures and reggae music.

—

References

[1] This was confirmed by Fausto Perea of Sonido Eckos, interviewed on December 16th, 2021.

[2] [3] See Richard TV interviews, https://youtu.be/9MjhaWt_JQU

[4] Fausto Perea of Sonido Eckos , interviewed on December 16th, 2021.

[5] Traditional percussion instrument from Mexico, already used by the Aztecs.

[6] An aromatic resin extracted from different tree species of the Burseraceae family, used since pre-Hispanic times.

[7] Ritual burning of resins and herbs on coals to cleanse and ward off bad vibes.