Street Systems and Knowledge Systems [SST Research 2.0]

Second in a series of blogs on SST research (read here the first piece), this article considers different knowledge systems in order to locate, recognise and give value to the ways-of-knowing of audio engineers. Knowledge comes not only from data, information or scientific laws; it is also embodied in the techniques and practices of SST engineering. Appreciating this is one of the major aims of our research project.

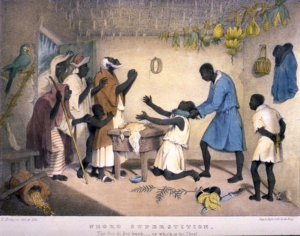

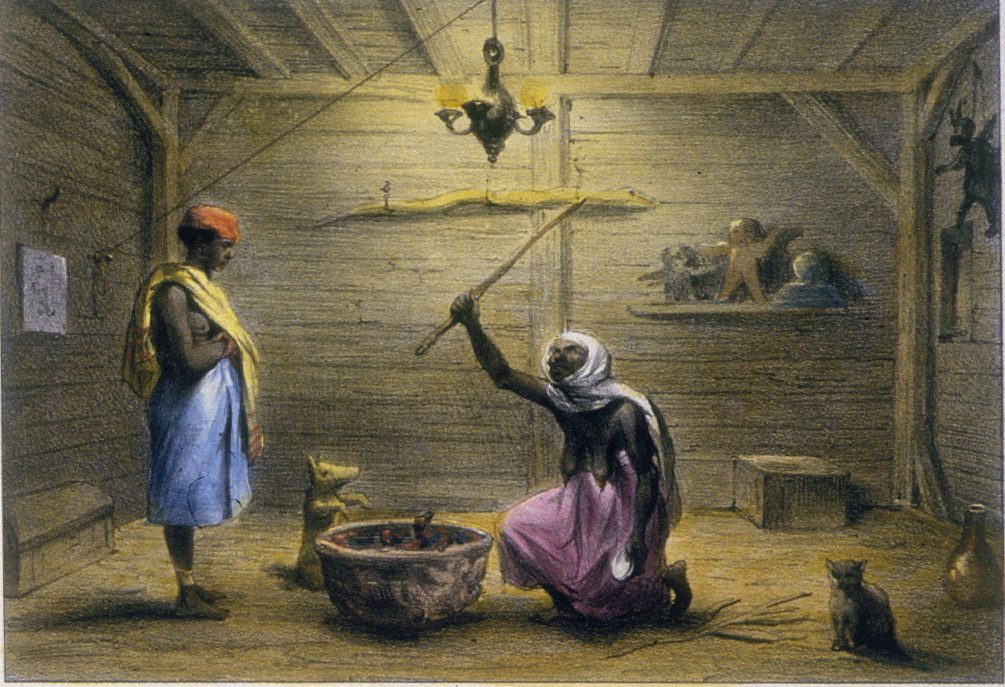

Starting with the skilled techniques of SST engineers, it has to be acknowledged that their work involves particular and specific ways of knowing, as well as particular and specific ways of making. In short, SST have their own identifiable modus operandi. The engineers’ approach audio engineering as a workshop craft, reliant on trial and error, re-purposing and “tinkering.” These ways of making produces SST that are bespoke and therefor unique to its engineer and owner. As would be expected, this kind of production process requires particular ways of knowing that are workshop-situated, embodied, tacit and learnt through apprenticeship (1). Most important, these ways of knowing include not only the components and circuits of the set of equipment, but also a deep understanding of the ways in which audio vibrations can be shaped and modulated effect and affect the bodies, hearts and minds of the crowd (audience). Indeed, it is essential for the commercial survival of the SST that they do precisely this – to intensify the lived experience of the crowd. The engineers would describe this “scyence,” that is the Jamaican term for black magic, Obeah or what in Haiti would be called Voodoo (2).

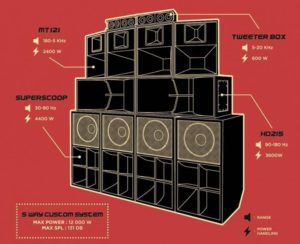

Historical and current subjugated knowledges: An Obeah practitioner at work, Trinidad, 1836; and sound system speaker box diagram .

Knowledge

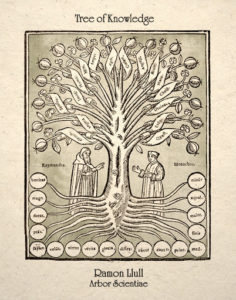

Exploring further the engineers’ ways of knowing it should be noted that their skilled techniques bridge what are most often considered to be two irreconcilable worlds. These spheres are on the one hand engineering and audio mechanics as an objective science and on the other subtle subjective world of sensation, feelings and affective intensities. While the ambition to reconcile quantities and qualities has long been abandoned by the Western science and rationality, it should be remembered this was the Pythagorean dream. In this the “objective” measure of the weight of an anvil or the length of a plucked string bears a direct relationship with our perception of the pitch of an octave. It is on these grounds that it is claimed here the SST engineers’ ways of knowing provide an example of a kind of knowledge that is distinct and different from the Western ways of knowing as epistemic knowledge.

Broadly speaking the epistemic knowledge is the kind embodied in scientific laws and textbooks. Michel Foucault describes an episteme as being generated by a range of elements such as “discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions…” (3) and so on. The assemblage of particular relationships between these elements generates the episteme. This makes possible – and this is the crucial point – “the separation, not of the true from the false, but of what may from what may not be characterised as scientific”(4). Thus the engineers’ ways-of-knowing are cast outside the rubrics of “proper” knowledge.

Thinking Otherwise

It is abundantly evident that these “other” knowledges – in the plural – have a literally always been there and indeed historically pre-date that of the episteme. Increasingly these have been recognised across an entire range of disciplines and fields of enquiry. Foucault described these “unqualified” and “subjugated” knowledge as

a whole set of knowledges that have been disqualified as inadequate to their task or insufficiently elaborated: naive knowledges, located low down on the hierarchy, beneath the required level of cognition or scientificity… (5)

Foucault gives examples of such knowledges as those of the sick person, or the nurse. In the present context this is of course the knowledge of the SST professionals which is often embodied, performative and expressive, rather than written down in a formal manner. As with oral cultures, they have been all too easily diminished and displaced by written cultures. Subjugated knowledges can also include indigenous knowledge systems of herbal remedies, for instance, or everyday embodied knowledges for cooking, hair braiding, weaving and the like. It cannot escape attention that such knowledges are often gendered female and relegate to the domestic rather than the public sphere.

Another way such formally unrecognised knowledges have been conceived is by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. They contrast what they call “nomad” science, such as SST engineering, with “royal” science:

What we have… two formally different conceptions of science, and, ontologically, a single field of interaction in which royal science continually appropriates the contents of vague or nomad science while nomad science continually cuts the contents of royal science loose (6)

It is what they call the “shifting borderline” between unofficial and official kinds of knowledge that this project aims to help to tip in favour of the former. The idea of nomad science is particular appropriate for SST given the fact they are often peripatetic. The regular practice of Jamaican sound systems is to “string up” (set up) in different open-air venues on different nights of the week, though there are also smaller dances at sound system HQ yards, in Kingston, as with Stone Love Movement’s Weddy Weddy Wednesday, for instance.

Alongside French philosophers, the idea of alternative knowledge systems to those of the Global North has been championed Latin American scholars. In Cannibal Metaphysics, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro offers and account of an indigenous worldview of a distinct and different character from those of the global north (7). The Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos has pioneered the concept of epistemologies of the South whose aim he states:

is to identify and valorize that which often does not even appear as knowledge in the light of the dominant epistemologies, that which emerges instead as part of the struggles of resistance against oppression and against the knowledge that legitimates such oppression. Many such ways of knowing are not thought knowledges but rather lived knowledges (8).

It is indeed the “lived” knowledge that has to be recognized and understood if we are to appreciate the achievement of the popular SST cultures. Santos’ work has achieved a significant impact destabilizing the once taken for granted Western monopoly of the idea of knowledge that is, of course, especially relevant in the context of current interest in “decolonizing” academic curricula. It should also be noted that such lived knowledges challenge the conventional definitions of the nature of knowledge itself.

As much as alternative knowledge systems have begun to receive recognition, it is also abundantly evident that it has never been a level playing field between competing knowledge systems, rather the exact opposite. The epistemic knowledge that claims to rely on text, data and facts occupies the dominant position atop a vertiginous mountain whose pinnacle the idea of Western modernist “progress” claims for itself. Indeed, the very idea of progress on which Western civilization founds itself has historically been defined as the opposite of those who lack civilization, to wit, according to Hegel, the inhabitants of the entire African continent.

James Snead in his seminal essay Repetition in Black Culture, describes the way possibly the most famous of German philosophers defined European civilisation as superior to all others. For Hegal the entire African continent was without logic, subject to the “immediate,” that is, what is always already there, and finally and most damming of all, without history. Snead translates Hegel as follows:

In this main portion of Africa there can really be no history. There is a succession of accidents and surprises…What we actually understand by ‘Africa,’ is that which is without history and resolution, which is still fully caught up in the natural spirit, and which here must be mentioned as being on the threshold of world history (9).

Without history, Hegel maintains, there cannot be progress and without progress there can be no civilization worthy of the name. It is this deeply embedded underlying notion of the superior nature of Western knowledge and civilization itself that the alternative knowledge systems seek to challenge, as is the aim of this project. In a similar manner, the modern scientific advances of the Enlightenment were predicated on extinguishing preceding knowledge systems, notably those of traditional women healers. Witch burning and drowning were at their height as Silvia Federici described in Caliban and the Witch (10). To put this another way, the master’s identity is dependent on that of the slave.

So, the battle between knowledge systems is hardly without consequences. In fact, currently more than ever before, it is a matter of pressing importance in the swirl of conspiracy theories, alternative facts and fake news that characterise the ongoing political environment. Knowledge, as Foucault famously taught us, is itself power. Thus, the battle to define knowledge is at one and the same time a battle to redress the asymmetrical distribution of power and resources between the Global North and the Global South.

As an activist and philosopher Angela Davis provides an incredibly useful way of characterizing the nature of the critique that is required. Davis calls the dominant knowledge systems the “the tyranny of the universal.” As she puts it:

Any critical engagement with racism requires us to understand the tyranny of the universal. For most of our history the very category ‘human’ has not embraced Black people and people of color. Its abstractness has been colored white and gendered male (11).

This is to say as long as the white male defines what is universal it does not universally apply inclusively to everyone. In fact, it is actively exclusive club open to some, while barring others (as explored in a further post). Molefi Kete Asante makes a similar point: “Universality can only be dreamed about when we have “slept” on truth based on specific cultural experiences” (12). It is the specific social, cultural and political experiences of domination that the knowledge systems of the Global North enjoy as the taken-for-granted norm, that other knowledge systems have to undermine. This is to be done on the grounds that the so-called “neutral,” or “objective” or “scientific” knowledge systems are as equally partial and particular as the West would deem alternative knowledge systems to be.

A last thought for this post comes from Franz Fanon. In the final pages of The Wretched of the Earth he despairs of the hope of finding any adequate conception of humanity from within the Global North. As he writes:

When I search for Man in the technique and the style of Europe, I see only a succession of negations of man, and an avalanche of murders… Let us decide not to imitate Europe; let us combine our muscles and our brains in a new direction. Let us try to create the whole man, whom Europe has been incapable of bringing to triumphant birth (13).

This research project aims to make a modest step towards realising this vast project to, as Fanon puts it, “set afoot a new man.”14 The one thing that makes such an ambition even conceivable is the fact that this new man and woman have for some time been striding out across the Global South and its diaspora as embodied in its own knowledge systems, as with those that engineer SST.

References:

(1) For a full account see Henriques, Julian. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques and Ways of Knowing. London: Continuum, 2011.

(2) See O’Neal, Eugenia. Obeah, Race and Racism: Caribbean Witchcraft in the English Imagination. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press, 2020.

(3) Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews & Other Writings 1972-1977. Ed. Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books, 2014: 195.

(4) Ibid. 197.

(5) Ibid. 82.

(6) Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia. London: Athlone Press, 1988: 137.

(7) de Castro, Eduardo Viveiros. Cannibal Metaphysics, trans. Peter Skafish. Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014.

(8) de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018: 2.

(9) Hegel, Die Vernunft in der Geschichte, 1955, trans. Snead, James, in Snead, James. “On Repetition in Black Culture”, in Racist Traces and Other Writings: European Pedigrees/ African Contagions, (eds.), Keeling, Kara, MacCabe, Colin, and West, Cornell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1981/ 2003: 146 (emphasis in translation).

(10) Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Automedia, 2014.

(11) Angela Davis, in a speech to a gathering of Ferguson protesters in St. Louis in 2015, https://artmuseumteaching.com/2017/10/11/changing-the-things-we-cannot-accept/ See also Sylvia Wynter, Scott, David and Wynter, Sylvia. 2000. “The Re-Enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter”, in Small Axe No. 8 (September 2000)

(12) Asante, Molefi Kete. The Afrocentric Idea, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987: 168.

(13) Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth, New York: Grove Atlantic, 1961/ 2007: 253.

(14) Ibid. 255.