Gathering an Archive of Sound Systems in Canada

In this blog post, two members of the SST Canada research team, Kavone and Betel, reflect on the process of gathering materials necessary to form an archival collection of ephemera. These preliminary, or in process reflections capture what we are witnessing in the midst of our work, and more importantly what we are not seeing as we search. While carrying out surveys of sound systems across Canada, we have bumped into, stumbled upon, nor simply heard of, a variety of materials – many of which we collect, take note of and utilize for future research. While there are many research gaps and ways in which the materials we find leave much to be desired, Kavone and Betel usefully identify and amplify some of what goes missing from the historical record, keep reading. – Mark V. Campbell, SST Canada research coordinator

by Kavone Manning & Betel Tesfamariam

Foundations of an Archive: Documenting Sound Systems in Canada

The roots of sound system culture in Canada follow the routes of Caribbean migration, technological innovation, and musical creativity within a diverse and expansive community. The documentation of sound system culture in Canada requires much digging and deep searches. Many of these histories are held in the community by elders and culture bearers and we, as Research Assistants for SST Canada, found more archival materials and content on public social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube than in published academic literature. This was no surprise to us as researchers, we continue to come up against a lack of documented histories of racialized communities in Canada. Despite this, we (Betel and Kavone) among numerous scholars move forward in archiving. As lovers of Caribbean music, this work connects directly with our own listening practices and what it means to tune into our histories. For me (Kavone), being Bajan-Jamaican and growing up in Toronto, gathering an archive is in special relation to my childhood and affirms the bonds to my heritage.

In academia, individual scholars have written their masters’ theses and dissertations on the influences of specific Caribbean genres on immigrant culture and the music scene in Canada. Sociologist Dr. Sara Abraham discusses the proliferation of calypso music from Trinidad to Toronto and the foundations of associations like the Calypso Association of Canada in 1982. Dr. Camille Hernandez chooses to focus on second generation Trinidadians, soca fetes, and Caribbean parties as sites where folks are simultaneously forming and performing their identities. These scholars, and others, point to the immense impact of the migration of people from the Caribbean to Canada, and the expansion of influence that Caribbean music had from the 1960s to the 1980s. Through migration from Jamaica, prominent sound system owners such as Leroy Sibbles and King Jammy, who had already formed sounds in Jamaica and were recording at Studio One in Kingston, moved to Toronto, bringing their dubplates and musical influences with them. Another notable Jamaican artist, Jackie Mittoo was crucial in popularizing reggae and dancehall within the Caribbean and Canada. As is shown here, sound system culture first lives in the community, amongst reggae and dancehall enthusiasts and community archivists like David Kingston, Carrie Mullings, Muscle, and Debbie aka MSDROPPINIT on YouTube. Our team has compiled this information in an annotated bibliography (A Sound System Archive in Canada). These resources highlight histories of resistance, which are linked to histories of creative production within the Jamaican and Caribbean migrant communities of Canada.

Some Key Individuals that Make this Archive Possible

Muscle, a former sound system member and owner of 2-Lined Music Hut, started the Entertainment Report Podcast in 2018. He has recorded and published more than 300 episodes of interviews with artists and sounds like King Turbo, Lindo P, Tasha Rozez, Rebel Tone and many more. He is a community connector who does extensive research and comes to his interviews prepared to engage his guests from all around the world in deep discussion about their upbringing, musical influences, and artistry. These conversations are very generative, and they allow us as listeners to learn about the history of dancehall, the history of reggae, and the scope of influence that giants like Bob Marley had on these genres.

Muscle being interviewed by Professor Mark V. Campbell at Luv, Not Likes, March 2024. Photo credit: Emma Radmacher.

Additionally, we have reggae and dancehall enthusiasts like MSDROPPINIT (Papa Melody International 1980) who is independently undertaking the monumental feat of converting hundreds of reggae recordings into digitized formats on YouTube. You’ll find archival footage of sound clashes and performances that took place in Jamaica, Canada, the UK, and the USA from the 1960s into the early 2000s on her pages. More public figures include radio host David Kingston as well as DJ Ron Nelson, who is a Jamaican deejay and radio host based in Toronto. Nelson has archived his Reggaemania radio show online and holds an impressive collection of resources on his website. Shout out our community archivists who we’ve had the pleasure of being in conversation with throughout this process!

We Create the Standard

It is worth illuminating how Caribbean migrants create their own standard of success in their business endeavors through sound system culture, and this legitimation process has carried on with each generation. Definitions of success, talent, originality, and creativity operate independently from the dominant institutional structures in the Canadian music industry. These dominant institutions within the music industry exclude the innovative countercultural and counternarratives invented by Jamaican sound system cultures throughout history. Sound systems are rooted in relationality from the music and the technology used to the movement, people, food, and conversations affirming the identity of Jamaican people. Our elders brought the seeds and planted new roots here in Canada for us now to enjoy the fruits of their labour. What we appreciated about the interviews on the Entertainment Podcast was how these artists were always looking back and offering up credit where they believe credit was due.

While we are at the beginning stages of our work, we are most curious about uncovering the gaps of the sound system archive of Canada, while showcasing the work of artists and community archivists working to counter these silences.

What is the silence in the archive? Where are the gaps in research?

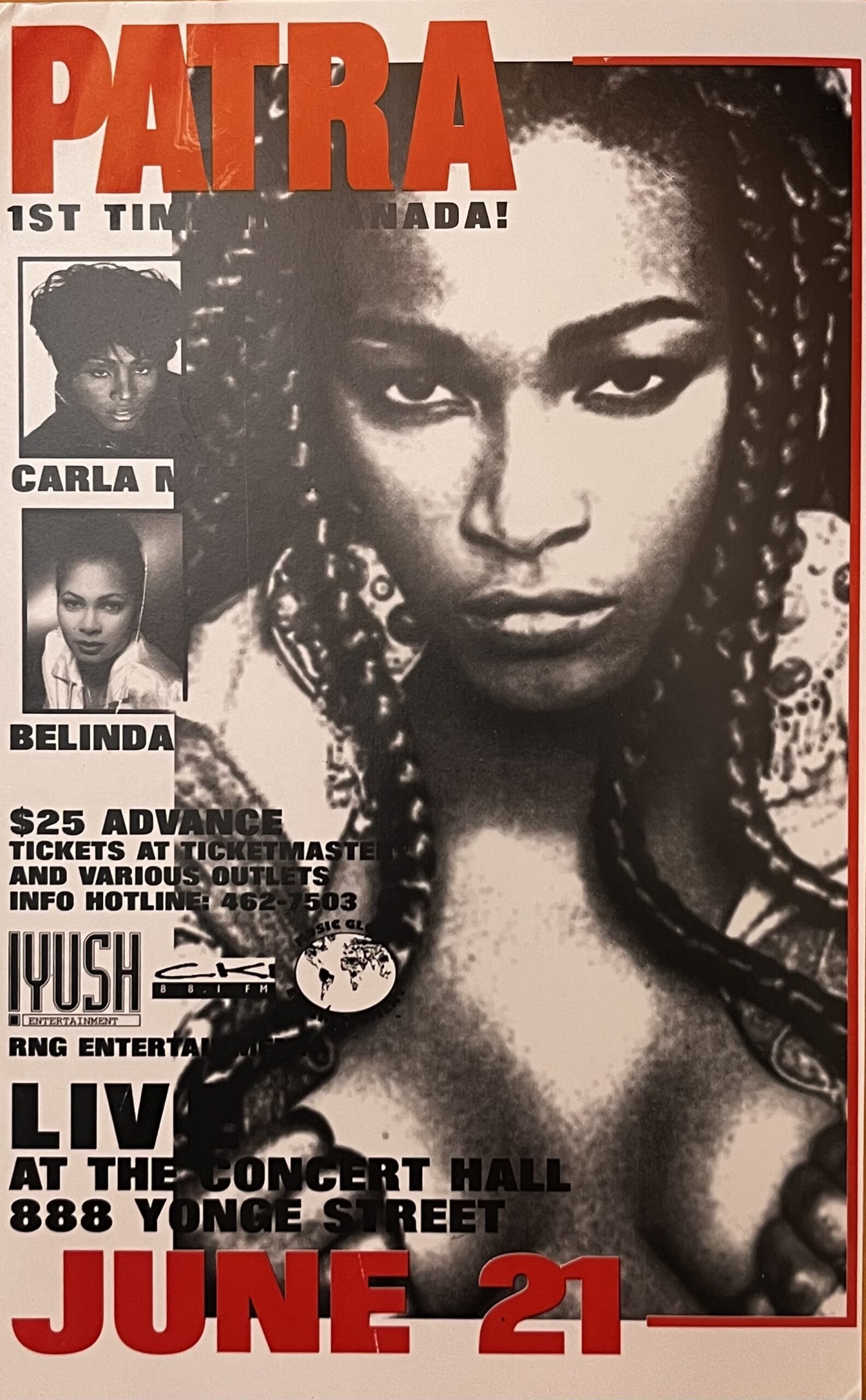

The most apparent gaps in historical research are women and queer artists. Here we are thinking of Vanessa Bling, Sister Nancy, Nadine Sutherland, Lady Saw, Spice and many more. These are monumental women in dancehall who are reframing narratives about empowering Black women, our bodies, and our sexuality. These gaps are slowly being filled by our current community archivists, who are bridging the gap between generations. These silenced voices intervene in our existing musical environments and build strength through collaborations and solidarity. Nothing about this archival work is linear or traditional. Instead, this experience continues to be cyclical and relational, contributing towards an expansive, resilient atmosphere.

Patra concert flyer, Toronto.

Queering Sound System Culture: Blackness, Creativity, & Technology

As part of Alanna Stewart’s multi-media exhibit “Rewind/Forward, Honouring the Goodness and Bawdness of Jamaican Music Culture’ directed by Graeme Mathieson, a two-part interview series with sound owners: Tasha Rozez, Bambii, Heather Bubb-Clarke, Ace Dillinger, and Nino Brown to highlight sound systems and parties by BIPOC women and femmes (Rewind/Forward Exhibition in Toronto, Canada). We see how some of these efforts to document sound system culture in Canada are also documenting the anti-Blackness that determined both how the music industry didn’t support these creative efforts (parties, artists) in the past, as well as currently in how anti-Blackness creates barriers for contemporary DJs to create inclusive, safe spaces and host parties. We learn about what John Wilson observes in his PhD dissertation, ‘King Alpha’s Song in a Strange Land,’ which is that sound system culture, the sounds, the clashes, and reggae parties, were sites where Jamaicans were claiming spaces of belonging and celebration.

DJ Ace Dillinger performing at Nuit Blanche 2024 photo credit: Knowtorietywhyz.

Deejays like Bambii and Nino Brown, who are creating inclusive party spaces for BIPOC LGBTQ+ communities on very different terms from the sound clashes or parties that were taking place in the 1970s or 1980s in Toronto. The deejays featured in this video project talk about sound system identification, the role of research and intuition in creating their sets and the evolution of sound system culture since the 1970s, when the selectors, deejays, and sound owners were primarily straight, cis, Black men. We are curious and encouraged to question how demographics of attendees at sound clashes and parties have evolved over time? They also address how anti-Black racism in Toronto shapes the party and music scenes. Specifically, they describe how anti-Black racism makes it difficult for them to host parties late, reserve venues, and book gigs, connecting these industrial barriers to the larger issue of policing historically, namely the policing of sound system cultures both within the Canadian context and the Caribbean context.

Further context for this structural anti-Blackness can be found in the shorter videos included in the ‘Resources’ section for Canada, for example in “The true story of Canada’s reggae capital” by CBC Music, which documents the gentrification threat faced by Little Jamaica on Eglinton Avenue, which was one of the largest reggae music producing scenes in the world outside of Kingston, Jamaica.

How do we make meaning of our experiences of sound system, dancehall culture now?

Alanna’s Rewind/Forward title has prompted us to think about the illusions of time and how the past foundations of dancehall culture remain strong and is pervasive in our spaces today. Dancehall is also simultaneously invisible and hyper visible. Our “invisibility” is that most of the knowledge is held with Elders and certain racialized communities. The hyper visibility exists because we’re Black and when we’re in community, we’re loud, we’re dancing, and we’re celebrating in comforting and extraordinary ways! The hypervisibility means we’re also vulnerable to surveillance and continued silences. We insist on honoring our Elders, while simultaneously looking forward to our role in creating space for the voices of queer DJs of color that contribute towards the claiming of an inclusive sound system culture that fosters belonging with each other. These layers of community building prompt us to question how we can contribute to bridging the gaps between generations while also creating an empowering, bold and queer space of resistance in sound system culture.

About the Authors

Kavone Manning (she/her) is an educator, musician and multidisciplinary researcher based in Toronto, ON. Kavone is currently completing her Master’s in Social Justice Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto pursuing research in Black Studies and higher music education. Kavone is an aspiring arts administrator committed to supporting Black sound discovery and expression.

Betel Tesfamariam (she/her) is a Black African feminist creative, educator, learning herbalist, and interdisciplinary researcher based in Toronto, Canada. Her political commitments and research interests lie in African and African Diasporic visual/sonic cultures and spiritual traditions as pedagogical and meaning-making mediums for critical explorations of power, blackness, gender, and the environment.