Sound Systems and Ecosystems

Sound system cultures have intimate histories that implicate them in global networks of ecologies, infrastructures, and multiple instances of environmental and energy justice issues. In this blog, Sonic Street Technologies Research Assistant, Aadita Chaudhury reflects on some of the ways these domains intersect and interact at the site of sound system culture’s development and practice.

When I joined the Sonic Street Technologies (SST) team, I came from a background in science and technology studies and political ecology. My previous research traces connections between global conversations about fire ecology, climate change and racial capitalism. I was drawn to the SST project because of the aligned concerns related to global racial capitalism and its impacts on As culture and technology and the spaces of resistance formed within this context. As a result, I would often navigate the new worlds of sound systems not only through the music and history, but also through stories of landscapes, ecologies, and geographies where they originated. As I started the social media ethnography and studies of sound system visual cultures last year, I began to think more about the centrality of the more-than-human in contributing to the co-creation of sound system cultures and scenes.

In the year 2020 in particular, cultural industries worldwide took clear note of their entanglements with the more-than-human world as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world. This led me to consider the various environmental systems and supply chains that are implicated in the creation and sustenance of sound system cultures.

At the heart of the ongoing operation of sound system cultures worldwide is a question about access to materials and energy. The key material in sound system construction is wood – plywood, often sourced from Baltic birch, originating from forests in Finland and Russia. The use of this plywood inculcates sound system cultures in an ecological supply chain that links specific histories of extraction, colonialism, Indigenous land conflicts and ethics surrounding modern forestry. Juxtaposed against that is the culture of repurposing, repair, reuse and frugal technologies that exist in sound system communities, and the extent to which they are effective in curbing some effects of this kind of extraction. Additionally, since many SST serve and are built from within marginalized urban communities, often with inadequate electricity infrastructure. Their development and proliferation as a site of community-building speaks to the innovative ways that communities address unjust energy infrastructures and environmental racism.

Legacy of environmental thought in sound system culture

While sound system cultures make visible many of the historical and contemporary social and environmental injustices, they are also a site for resistance to capitalist modes of extraction in relation to the more-than-human worlds. The culture of repair, repurposing and reuse that pervades the ethos of innovation in many sound system scenes is a testament to going against the culture of planned obsolescence that marks much of the ideals of 21st century technological praxis. In addition to this, many of the genres that are represented through sound system cultures, such as reggae and dub, have always shown a deep commitment to human responsibilities to and as part of wider ecosystems.

To learn more about the presence of ecological ideas in dub and reggae, I turned to the SST project’s new Researcher and Research Manager, Natalie Hyacinth. Natalie has noted that dub and reggae cultures have always been attentive to human responsibilities towards the Earth. She presented me a few examples where artists made explicit this responsibility through their music.

In Natalie’s words, this song from the UK dub scene is one that “can be interpreted in various ways, but it has always struck me as an earth first anthem. Reggae and dub artists have always sung about the need to look after our Earth and natural environment.”

“Man in the Hills is a roots classic from 1976”, explained Natalie. “Burning Spear is imagining the natural environment as a place for escape, survivance and peace. There are lots of resonances of this desire to be in nature throughout roots music, a sort of mythology around the hills, the forest, green land, etc, as with the Rastafari camps in Jamaica.”

“Roots Hitek’s album, Green Places is also a good listen for these sorts of ideas. He has a track called ‘Ecology Dub’ on the album.”

“A lovely song by the late, great Akae Beka, part of the new roots movement with ideas very connected to land, nature and ecology. I love the lyric, ‘rising water levels eating land like cake’,” said Natalie.

Through my own exploration, I also found several other songs that speak to ecological themes in explicit terms that go to the roots of environmental degradation originating from the ideals of development that centre a Euro-American extractive culture.

Jamaican dub poet and musician Mutabaruka’s “Ecology Poem” from 1991, speaks explicitly about ecological collapse rooted in global extractive practices.

Lion Zion and the Heptones song “Gas Guzzler” from 1976 explores the ennui and frustration surrounding the imposition of car culture on domestic life, and the ensuing effects on familial, ecological, and economic relationships.

Another 1976 song by Lion Zion called “Who Killed the Buffalo?” reflects on the massive culling of buffalo herds in the plains of North America in the 19th century by the settler colonial governments of what is now the United States and Canada, as a way to disrupt Indigenous lifeways and facilitate easier annexation of Indigenous lands.

Contemporarily, the many Black musical traditions outside of reggae and dub, such as jazz, soul, funk, and Afrofuturism-inspired music also centre environmental thought. The legacy of environmental racism faced by many Black communities is palpable in these cultural creations. I would contend that similar themes are also explored in other communities involved in the technological diaspora of sound system cultures.

At this point, the practitioners and artists have already persistently attended to thinking critically about their ecological relationships. It remains to be seen how these responsibilities are further entrenched in reflected in the practices of research surrounding sound system cultures and other cultural forms. However, an environmental turn informed by these racialized histories of the environment in relation to popular culture would be a great basis to transform thinking through culture as a co-production between human and more-than-human worlds.

Wood and coltan

Thinking through the environmental visions present in reggae and dub, and the technological ethos of sound system cultures, it is interesting to consider how the material ingredients that create sound systems function as part of global ecologies.

I have always been interested in how the more-than-human worlds influence artistic practice. Informed by my background in political ecology, I brought a particular attunement to the ways that the environment enacts agency within the realm of sound system cultures. One of the key features of building sound system involves sources the material components. I learned from several sound system operators that the soundboxes are an important feature in creating and amplifying the sound and character of each sound system. The most popular choice for soundbox construction seemed to be Baltic birch plywood. The extraction and global proliferation of Baltic birch plywood is a key place to think about the historical and ongoing legacies of extraction that is enacted through sound system cultures.

Construction of sound boxes is an important part of creating a new sound. Here, we see Creative Dubs, a Belgium-based sound system, documenting their construction journey on Instagram

From my previous research in fire ecology and forestry, I came to understand that much of modern forestry practices rooted in German scientific forestry sought to see forests not as consisting of pluralities of communities and ways of being between human and more-than-human worlds, but simply as sources of timber. To standardize timber production, German scientific forestry traditions began to reimagine forests as idealized monocultures. As German timber industries undertook efforts to make forest ecosystems reflect this idealized version with predictable timber yields, they displaced ancient forests and their embedded human and more-than-human lifeworlds, with severe ecological and economic consequences. This is the root of the commercial forestry plantation system. This system of forestry still informs current practices. Within the context of Russia and Finland where Baltic birch is sourced, forestry is associated with a long history of contestation with local communities and Indigenous peoples.

Through considering the origins of sound system cultures in Jamaica and other Caribbean nations, other histories of contestation with regards to wood also make themselves apparent. As many communities in the Caribbean trace their roots in the transatlantic slave trade, the history of marronage – the act of fleeing the plantation to create independent communities that lived off the land – is a rich space to think through emancipatory politics. In many instances of marronage, enslaved people would find refuge in the forests and hills in the Caribbean and in many parts of the United States. These landscapes would then go onto be animated with stories of liberation and hold an important place within anti-slavery struggles as a site for the ongoing practices of imagining other worlds. As sound systems came to be developed in the mid-20th century in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean, it is interesting to speculate how such narratives surrounding the forest as a space for liberation and imagination also reverberated as wood was sourced from many local sites. It is as if the forest’s role as an emancipatory technology found new form in the wooden soundboxes.

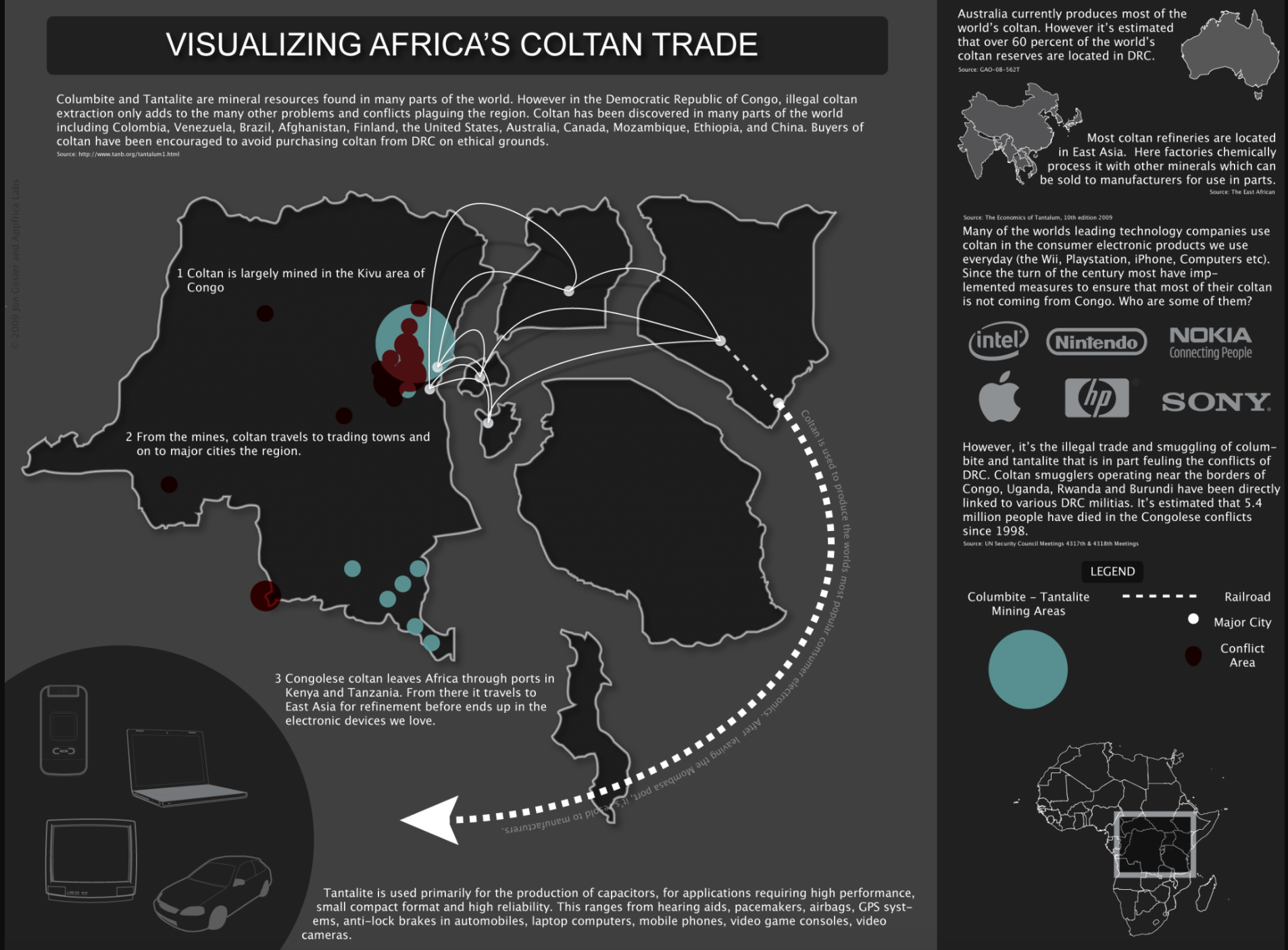

In recent years, sound studies scholarship has also attended to the ways that the environment is implicated in aural practices through electronic infrastructure. Chiefly among these considerations is looking at how coltan – a mineral present in all electronics – transforms the space for practice. Coltan is often sourced from African countries such as Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. The politics and practices of mining in these countries are closely entangled with global economic frameworks in extractive and exploitative ways such that coltan is termed a conflict mineral. Child labour, deliberate exploitation of communities by governments or militant groups, exposure to poisonous chemicals and other risks as a result of insufficient environmental protection have all been linked to coltan mining. However, coltan’s sustained presence in electronic appliances, many of which are used in the sustenance of many music scenes, is something to consider with further depth.

Infographic showing Coltan’s supply chain throughout the world. (Souce: https://phys.org/news/2010-12-tracking-conflict-minerals-congo.html)

Given the complex legacies of both wood and coltan in the context of sound system cultures, it provokes one to ask – how can sound system culture navigate its promises and emancipatory possibilities, given that its material conditions are already embedded in global networks of resource extraction? How can the sound system community respond to these entanglements more conscientiously?

Energy and Power

Sound system culture also exemplifies practices that are associated with legacies that are symptomatic of environmental and energy justice concerns. The practice of acquiring electricity from established power lines is a strategy often seen in the operation of sound systems in marginalized communities. This configuration of subverting legal means of obtaining electricity speaks to the infrastructural disregard that many global cities are faced with. In combination with other means of resistance that sound systems mobilize, the extra-legal use of electricity shows the extent and types of injustices that often surround communities that create sound systems.

Afterthoughts

The nexus of sound system cultures and technologies, environmental racism, and energy justice is a rich place to think through the multiple histories and ecologies that have always shaped sound system cultures. The politics of survivance implicated in practices of sound system culture call into question how the environment can act as an ally in emancipatory struggles. However, the nature of the supply chains implicated in sound system cultures also troubles the extent to which such promises are manifested, and at what cost. Nonetheless, given reggae and dub’s ongoing commitment to and tradition of environmental thought, combined with the increasing consciousness across many performing arts communities about the ecological challenges, it would be interesting to see how sound system communities respond to their ongoing relationships with the more-than-human.