Research Fun at Goldsmiths

On March 11, 2022, we gathered some friends and colleagues at Goldsmiths for an in-person meeting. This was not to share our research findings in the usual way but – but instead to brainstorm and share research ideas in an informal setting. The invitation read: “…the idea is just to get the conversation going across fields and disciplines, and to unpack how we may reconceptualize ways of thinking about the material and theoretical components of the SST project.” The response was instant and positive – this is what colleagues had been missing on account of the pandemic and strike action against the management’s restructuring and staff redundancy plans for college.

Being part of the Sonic Street Technologies team is the first time I have been engaged in a collaborative research project. In my own dissertation research, I follow threads of inquiry that place me and my fieldwork at the centre. However, for the Sonic Street Technologies projects, there are numerous threads of inquiry, spanning several countries, communities, music genres and ways of being.

We have made use of research agents across four continents who contribute to our overall research objectives from their locations. We brought these local research agents together in the Researchers Community Meeting in December 2021, which was the first in what we hope to be a series of meetings involving the researcher community.

Still, as I reflected on the overall research process, I felt something more could be done to engage with what we had been tending to. Inspired by thinkers such as adrienne maree brown, Zoe Todd, Erica Violet Lee, bell hooks, Octavia Butler, and Christina Sharpe, I often think of the act of doing research, at whatever scale, as an act of world-building. So, on the surface, while we had been tending to the different moving pieces of the Sonic Street Technologies project. I felt we needed more embodiment in our research ethos.

Members of the project team have in the past written about the place of practice-as-research in the context of sound system cultures, however, due to the limited access to the field during pandemic conditions, all of us have been missing the element of embodiment in our research practices. What’s more, with remote working conditions, I felt that the organic weaving of ideas and the spontaneous communities that are built through in-person (but often unplanned) intermingling of bodies in the university space were missing in our research thus far, and was concerned about its impacts in the future of the project. With so many moving parts, I also wanted to create the space for conversations to be had about the pluriverses that existed, that we perhaps could not see, in our existing research contexts.

Joseph Dumit’s method of “object implosion”

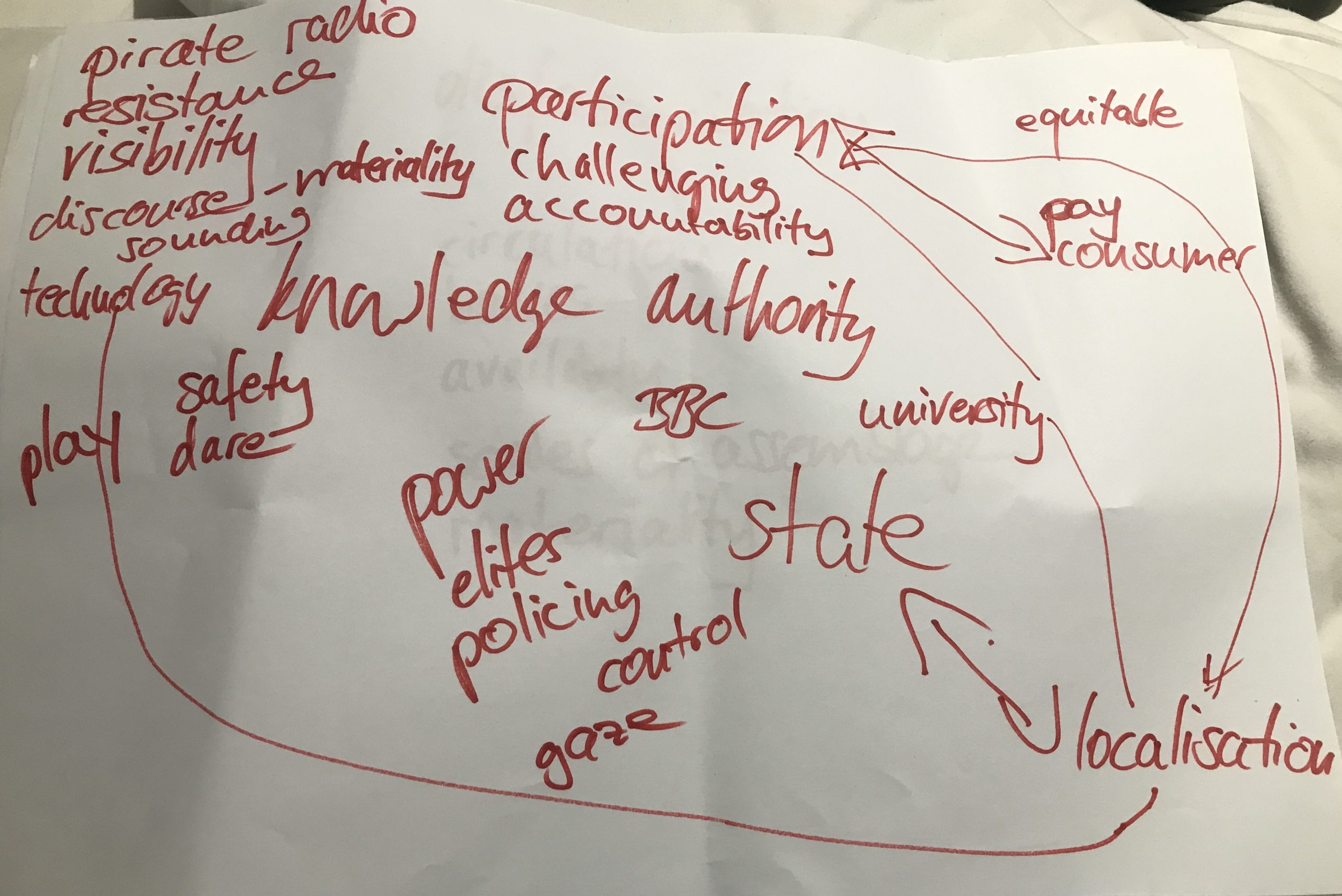

Once I knew that it was imperative that we bring in the larger research community into our work, I also wanted to ensure that no participant in our processes required further reading in order to engage with the work that we were doing. So I looked to Joseph Dumit’s pedagogical tool, often termed “object implosion” as a way to guide discussions. In its core essence, the “object implosion” method asks us to reflect on how an object exists in the world, and how the world exists inside of the object. This process of inquiry asks participants to see how objects may influence and be influenced by wider material-semiotic, biophysical and environmental contexts of the wider world. For our purposes in community building, we wanted to simplify this process even further. Namely, we chose the following concepts and objects, and asked our participants to riff on it, based on their own research interests, lived experiences and ways of being:

- Sounds

- Streets

- Technologies

- Diasporas

- Communities

- Knowledges

The conversations that arose from these prompts created a rich texture that we as a team will have a lot to think about. It is specifically in the spontaneity, the lack of pressure and outcome-independent nature of this inquiry that facilitated the revelation of the richness of everything that is in our research ecosystem, that we had not yet considered. By the playful nature of the inquiry, we also were able to access parts of our beings that had been cut off from modes of inquiry that were non-linear. By the end of the group brainstorming sessions, we had some potent text and images to think with for the future.

As the brainstorming session ended, we were left with a plethora of perspectives on the different directions that the Sonic Street Technologies project can take. While a wider network of concepts, such as embodied knowledges, coloniality, sonic ways of knowing and diasporas, are already part of our general lexicon, we also found a patchwork of interpretations surrounding these concepts that will no doubt serve the future twists and turns this project takes.

To end the afternoon, Julian, Brian and myself wanted to present some sounds and images that were meaningful drivers to us in understanding the global context of sound system cultures. This was not only meant to trigger further theoretical discussion, albeit informally, but also a way to bring our own selves, identities and interests into what we are doing.

I started my “show-and-tell” with an image of Charles Owens and his family, taken around 1943 in Bridgetown, Nova Scotia.

Source: Helen Creighton Folklore Society

This picture was presumably taken by Canadian folklorist Helen Creighton, who at the time, was collecting traditional Black music in the historical communities in and around the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Charles Owens, in this picture, is supposedly about a hundred years old, and he contributed a number of songs to Helen’s archive, some of which was released as an album in recent years, Sankofa Songs. When reflecting on the role of diaspora in the creation and dissemination of sound system cultures around the world, I wanted to reflect back on African-Canadian communities in Canada’s east coast, one of the countries which I call home, and their own histories of migration from the US as British loyalists or as migrants through the Underground Railroad.

I also presented the following image of the Jaipur foot, an example of Indian frugal innovation, or jugaad, which made prosthetic legs far more affordable to many in India since the 1960s. Since frugal innovation is also a key part of sound system culture, jugaad became a way of understanding how a similar way of creating technology also exists in my country of origin.

Our Senior Research Assistant, Brian, presented an image that is apparently an iconic site in his home city of Naples.

Brian wanted to draw our attention to how public and private spaces merge in the clotheslines that hover above this street in Naples. This practice of shared clothes lines between apartments that are situated across from each other highlight a feature in street life in Naples that is based on cooperation, and in the act of creating such a small feature of infrastructure surrounding it, residents of Naples cause a spillover from their private spheres into the public foray of the street.

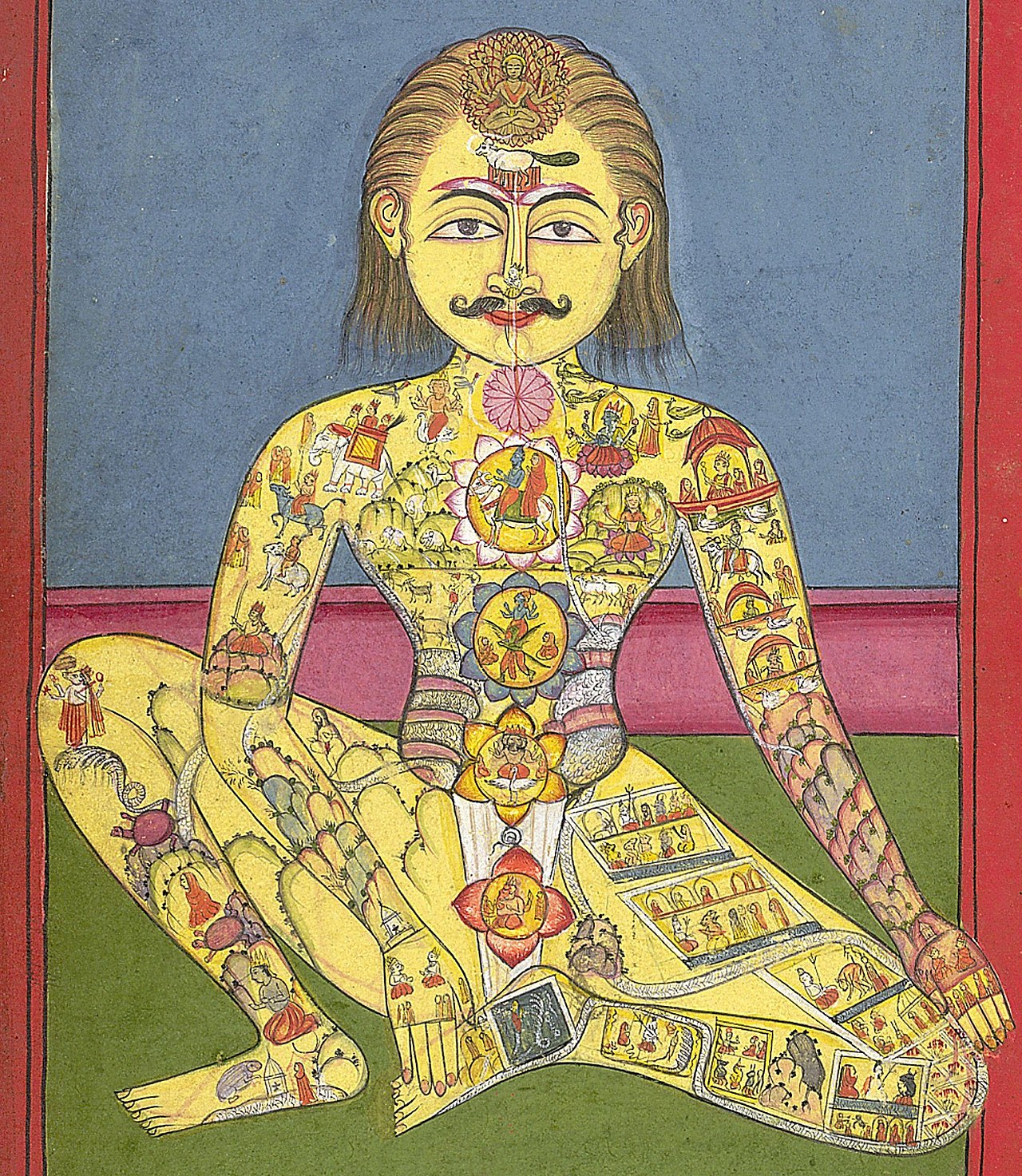

Finally, Julian discussed the following image of the subtle body according to yogic knowledge systems.

The Subtle Body: Sapta Chakra, from a Yoga manuscript in Braj Bhasa language, 1899, British Museum, Wikimedia Commons. Note the chakras, or vibrational energy centres, descending from the crown of the head to the genitals.

Using this image, Julian wanted to illustrate that other ways of knowing the body – and the importance of seeing the interconnected of the mind and the body, in contrast to the mind-body split that Cartesian dualism proposes. In perhaps the most apropos way to end the afternoon, this image brought us back to why we framed inquiry the way we did today – through play and whimsy, so as to escape the imposition on our ways of knowing and being that Cartesian dualism places upon us.

Looking forward

As we ended the afternoon, we made our way to a local pub. After nearly two years without in-person collegiality, this was a welcome change. I was struck by how seamlessly we weaved between different conversational registers throughout the course of the afternoon and beyond; from academia, philosophical and historical traditions, the ongoing labour disputes across UK universities, and life in general. Although we still have some ways to go, it felt like the afternoon and the activities we did set a tone for what is to come in the future for us at Sonic Street Technologies. While we are still to various degrees navigating pandemic conditions, and negotiating a wide range of accessibility challenges as a space in the university, perhaps being together and thinking together, outside of prescriptive academic terms can lay future groundwork for world-building beyond the present status quo in academic inquiry. In spaces of emergence, especially when dealing with concepts, articulations and phenomenon in flux, it appears that an orientation to play serves us well in navigating the way forward.