ELEVATING THE CULTURE OF LOVERS’ ROCK. INTERVIEW WITH COLIN BROWN aka CEEBEE MULTIMEDIA

Sonic street technologies’ relationship with music is organic and two-folded. The music can go from the street sessions and the house parties to the charts, and back again. The case of lovers’ rock is particularly representative. A homegrown British subgenre of reggae infused with soulful melodies and romantic lyrics, since the mid-1970s lovers’ rock found in Black British young women both its stars and its audience. The commercial success contributed to reshape not only the sound systems’ music program but also the mainstream British music landscape. Guest blogger Yassmin V Foster interviews Colin Brown, curator of The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition that was held in Croydon, London and Birmingham in 2022-23.

Text and images by Yassmin V Foster

“It felt like it was coming from heaven before the bass dropped in”

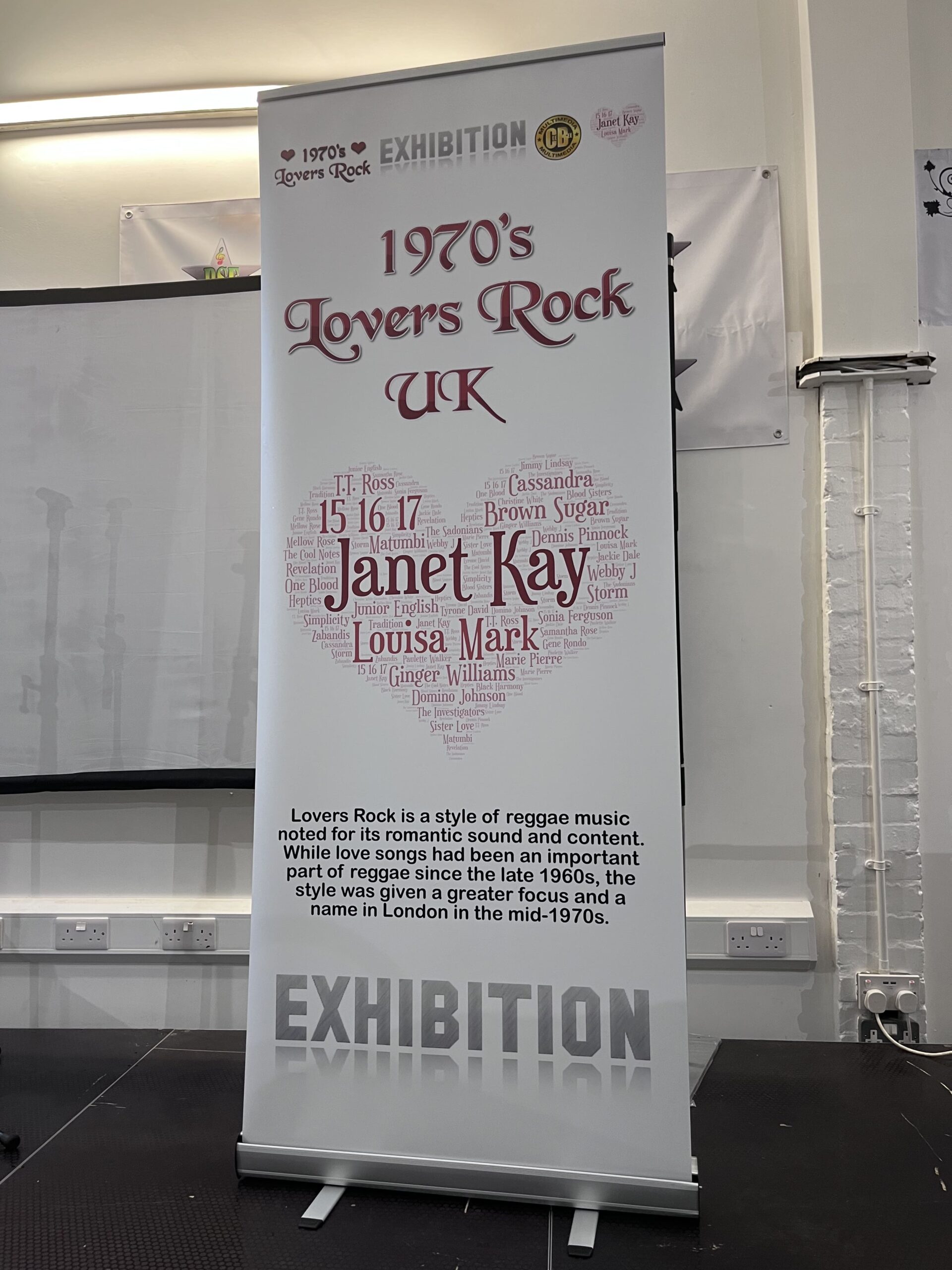

Lovers’ Rock is a slow and melodic reggae genre co-authored by Black British youth during the 1970s, the era would not be complete without its dancing spaces and sartorial epithets. Named after the fact, the first in a catalogue of lovers’ rock music was a cover of Robert Parker’s (1967) Caught You in a Lie, by 15-year-old Louisa Mark in 1975. Black British youth had welcomed reggae and sound system culture from Jamaica, as a barometer and disseminator of thoughts and feelings about themselves. Lovers’ rock is a meeting of a coming of age, aspiration, introspection and resistance bound in the expression of sound and movement. The genre’s bass notes are perfect for the sound system and the physical exploration of frequencies found in lovers’ rock dance. Brown, a teenager at the time, remembers his first experience of hearing The People (circa 1978) by Noel McKoy & The Albians, he says: “it felt like it was coming from heaven before the bass dropped in”. The lyrical content of lovers’ rock is extrapolated from the experiences of the community which is collectively redressed in social spaces like houses and community centres. The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition curated by Colin Brown is the first of its kind and launched at Brent Black Music Co-op (BBMC) in Willesden London, October 2022.

The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition at BBMC, Willesden, 2022

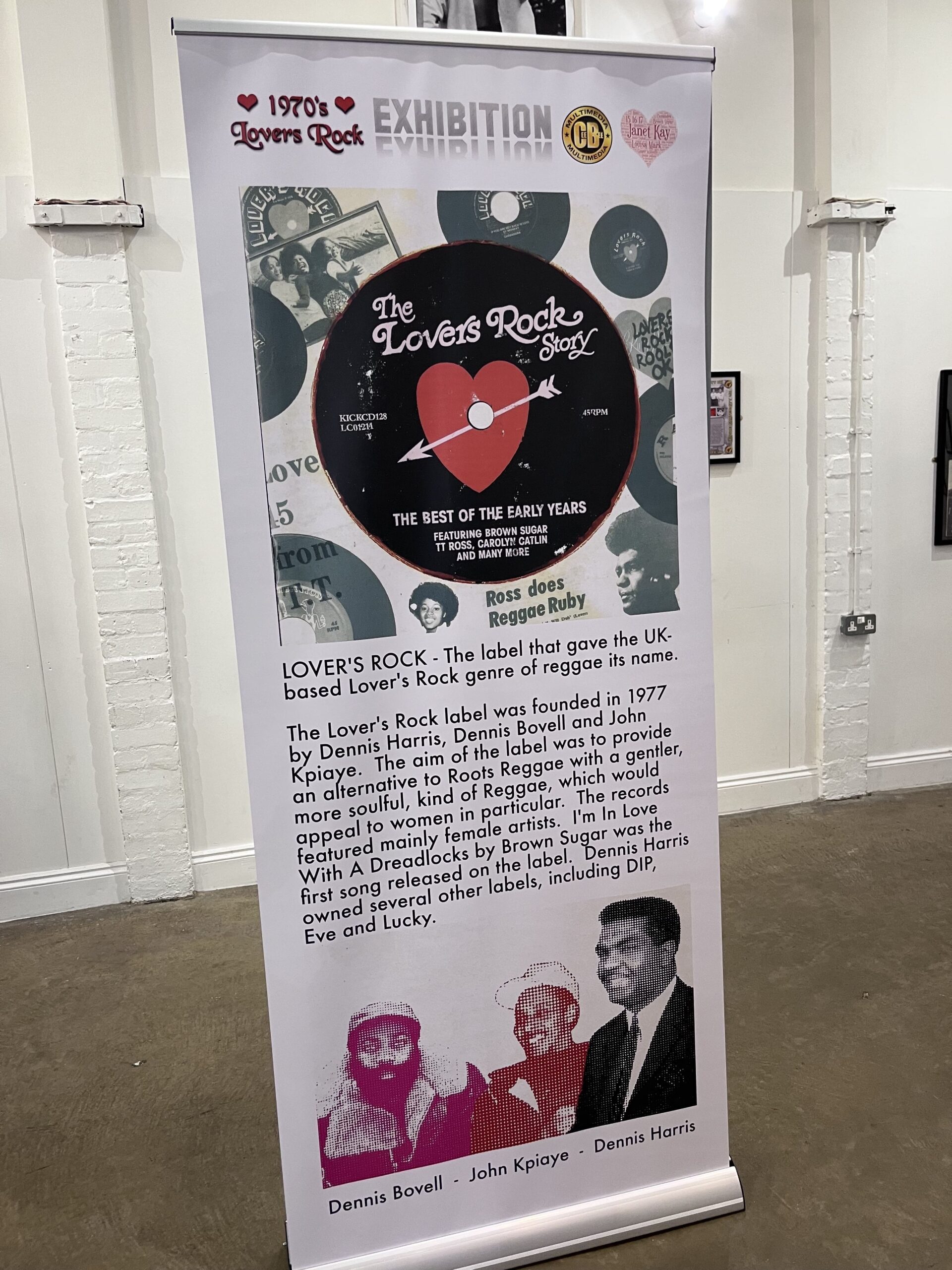

Brown’s firsthand experience of lovers’ rock is visible in the exhibition’s design, the heart shape is a recognisable symbol for the genre seen on the record company of the same name. Album covers have been carefully chosen to underscore the timeline of the period and help to visualise an almost hidden economy. Brown has placed the foundation years of lovers’ rock music and music makers at the helm of this seminal piece of work, in an effort to document its importance in the epoch of reggae music in Britain. In addition, to track the evolution of the genre from romantic reggae of Jamaica to lovers’ rock of the UK. Charting the success of this “British” reggae music genre through images, text, music and events, the exhibition went on to be installed at Whitgift Centre in Croydon (January – April 2023), the Legacy Centre of Excellence in Birmingham and the Phonographic Performance Limited in London (October 2023). Curatorial decisions like making the exhibition lightweight as mobile as possible have ensured that it can be appreciated by audiences up and down the country. Knowing that lovers’ rock has been equally instrumental to Black communities outside London means it can always be in demand.

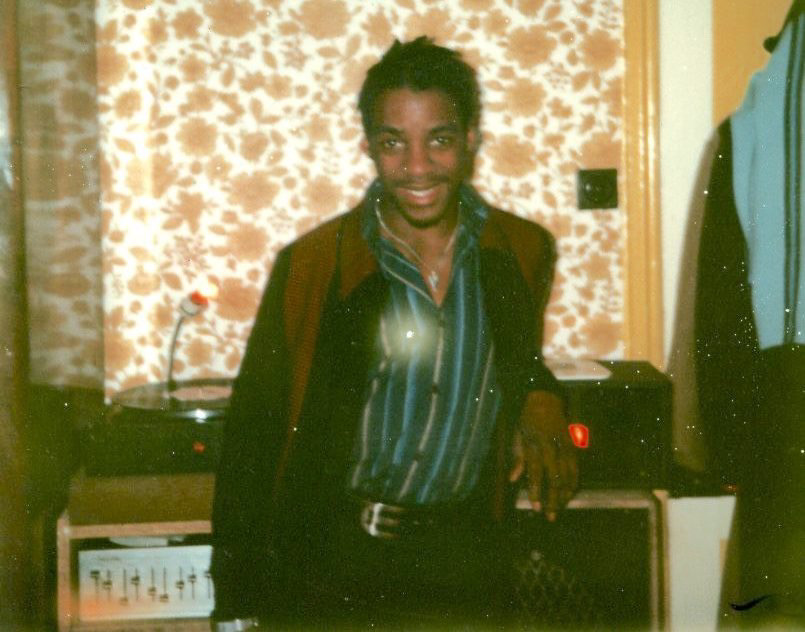

Colin Brown, circa 1970s

“I said I was gonna put on an exhibition, and then I had to”

Brown, the secretary at Reggae Fraternity UK (RFUK), is a video and audio specialist with a long-standing career in data mining. He is well versed in the experiences of the era, its music and overall place in British society. His affinity to claim lovers’ rock as a British thing and of a Black experience coupled with its sparsely documented history is the catalyst for his research. The project was intended as an online exhibition titled Lovers’ Rock Occasions, but Brown and RFUK were unsuccessful in securing the necessary funding. Brown was reminded of “self-reliance” in the wake of COVID-19 and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, this inspired him to keep going. At the same time, BBMC approached him to do an archival project, which became The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition.

“One of the arguments about lovers’ rock is that Jamaica started it”

Back in 2020 Brown expressed his plans for the exhibition to Queen of Lovers’ Rock Carol Thompson, she championed its relevance. He says, “one of the arguments about lovers’ rock is that Jamaica started it”, and this is why he focused on the foundation years of the 1970s. Chronology was fundamental to Brown and is pivotal in the framing of the genre, so visitors get to experience a linear unfolding of lovers’ rock. Citing the “consumption of a decade” as a method used to discuss pop music, he too employs it to counteract the pitfalls that may come with the “evidence of memory”. Brown took inspiration from the Saatchi gallery and Colin Robinson’s Reggae Museum series (see also this blog). His research included purchasing multiple editions of Black Echoes and Black Music magazines. Brown believed that “the usual suspects are always spoken of when it comes to discussing lovers’ rock”, which meant that it was important for him to show a fuller reflection of the landscape.

“Whilst all other genres are selling 1000s, lovers’ rock is selling 10s of 1000s”

The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition at BBMC, Willesden, 2022

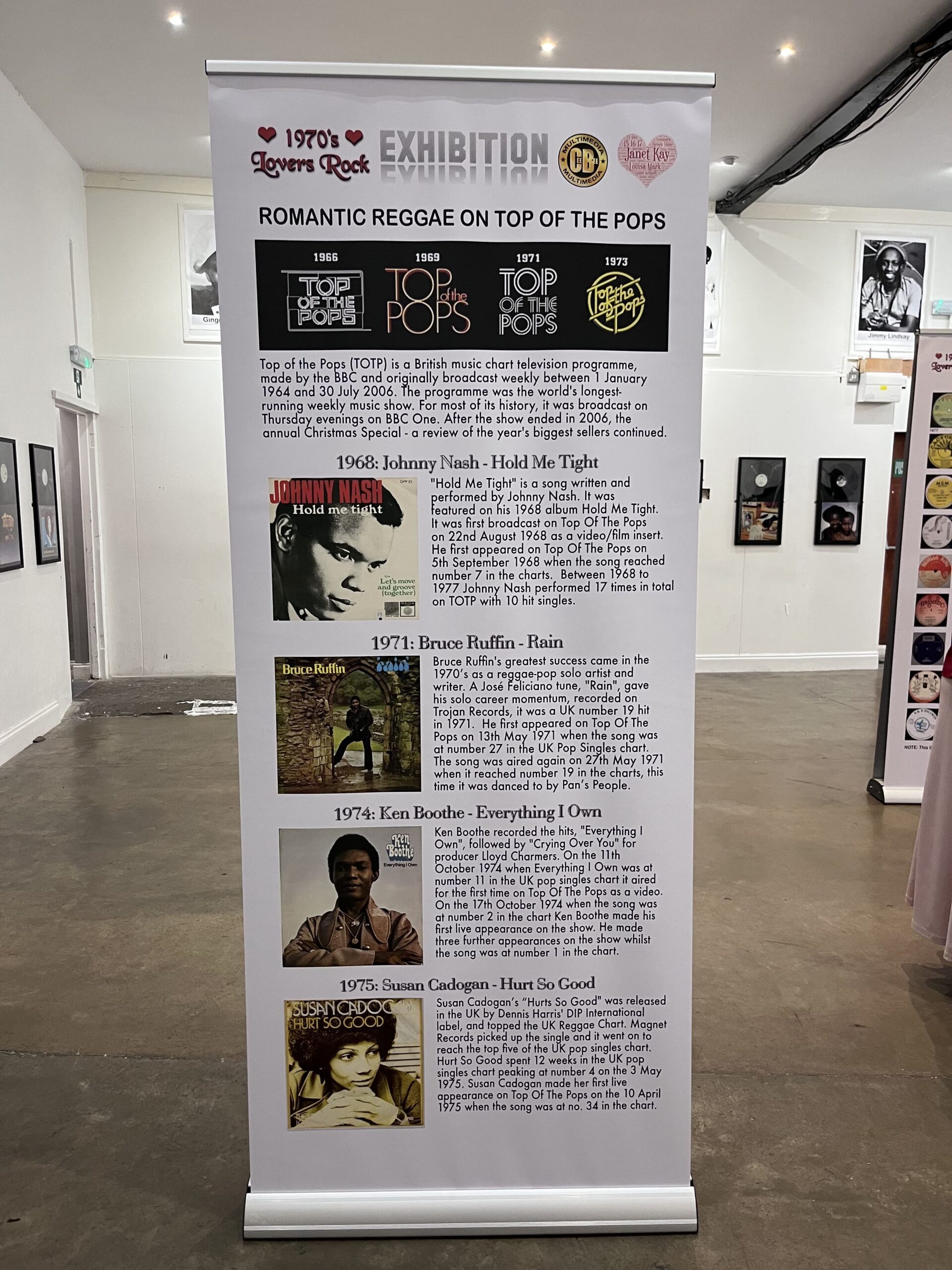

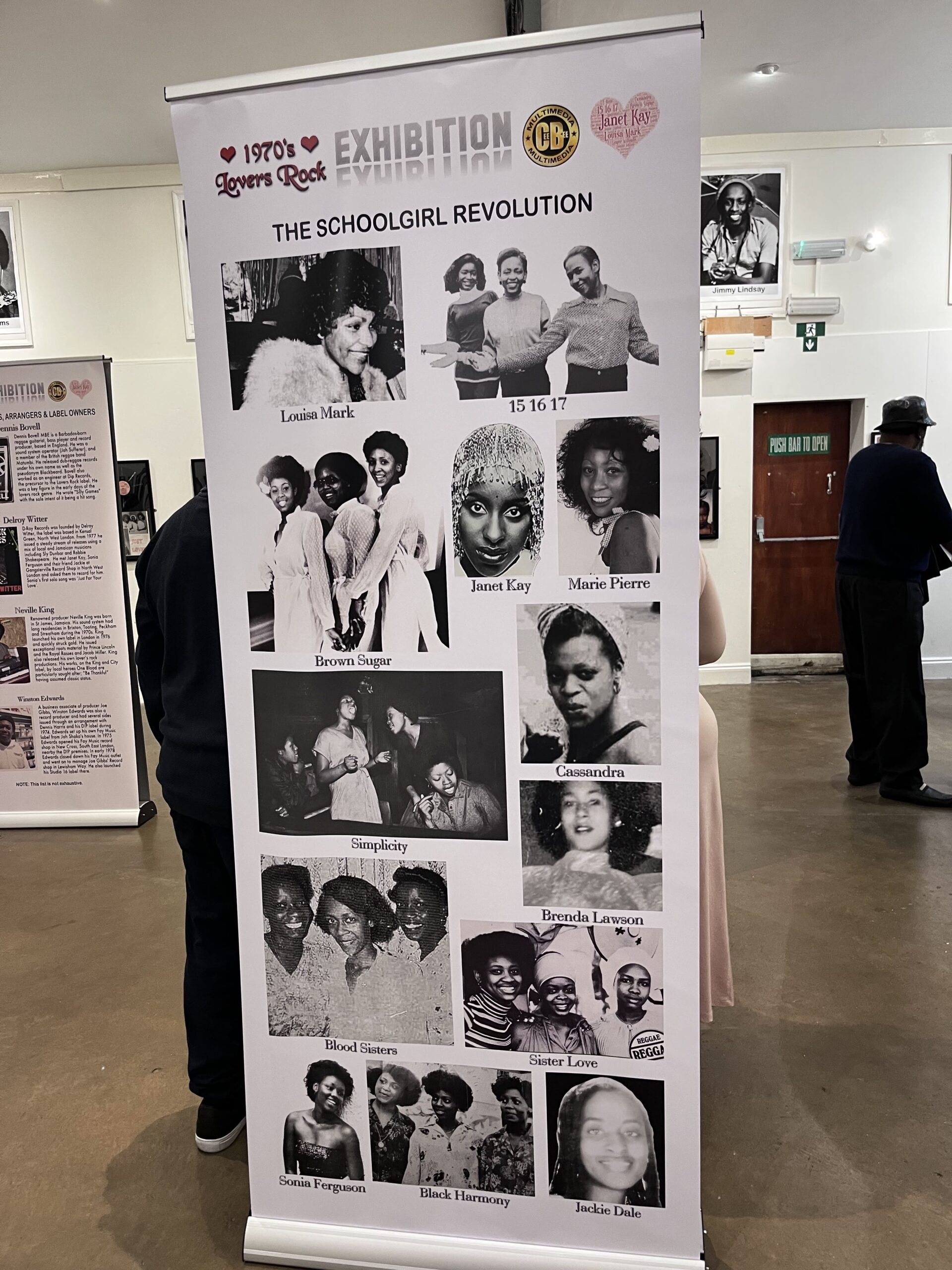

Brown knew what he wanted for the perimeter of the exhibition but had not yet decided on what would feature in the centre. He created zones that spoke to topics in the theme, and more importantly, they brought the exhibition together. The narrative that ran through the exhibition became clearer as Brown’s research unearthed further evidence of lovers’ rock as a distinctively British sound. The early years of lovers’ rock would not have been possible without the artists 15,16,17, Louisa Mark or Sister Love, to name a few. Equally as relevant to the music makers were the schoolgirl consumers that bought the records. Equipped with disposable income, Black British schoolgirls became the largest demographic in the genre’s consumption. This resulted in sound systems having to dedicate part of their night to lovers’ rock. “Whilst all other genres are selling 1000s, lovers’ rock was selling 10s of 1000s, that’s why you are hearing them on Top of the Pops” says Brown. The most iconic performance was Janet Kay with Silly Games (1979) with its crossover into the UK pop charts.

“If you are honest with yourself, it’s not the people who arrived here that made it”

The curation saw several lovers’ rock artists take their rightful place across the walls of the exhibition, these included Ginger Williams, Junior English, Brown Sugar and Jimmy Lindsay. Brown located the genre’s pioneers of past and present to ensure transparency and credibility for the community that made it and that it served. He argues “if you are honest with yourself, it’s not the people who arrived here that made it”, the schoolgirl revolution of lovers’ rock is proof of this. Crediting Jamaica’s romantic reggae as present in the backdrop to the foundation years of lovers’ rock, Brown’s research identifies Jamaican artists who have earned a seat at the lovers’ rock table. Many who migrated to Britain during the 70s and 80s became part of the developing scene and are credited as such, these include Ken Boothe, Susan Cadogan and Dennis Brown.

The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition at BBMC, Willesden, 2022

“When the argument arises about if lovers’ rock is Jamaican or British, name a country that has this many young girls, the volume of young girls makes it a phenomenon”

The ambition was to have part of the exhibition as an installation, specifically a schoolgirl’s bedroom. In his experience, Brown suggests that from around 1977 women started to visit the record shops, with their lists of records that they wanted to buy. That, teenagers especially women, were able to buy songs that spoke to them. There was recognisable change to sound system culture and record sales, however, record stores were not chart stores, so the sales never registered on the national charts. Brown’s double-sided banners that occupied the central space of the exhibition, pays particular attention to the phenomenon of Black women in the British music industry. Naming thirteen schoolgirl artists in this way is the beginning of understanding the size and significance of a generation of Black people. “When the argument arises about if lovers’ rock is Jamaican or British, name a country that has this many young girls, the volume of young girls makes it a phenomenon”. There is an undeniable truth that stares at you from these human height banners, that imprints the presence of these musical mavericks into your consciousness.

The Lovers’ Rock Exhibition at BBMC, Willesden, 2022

“In the face of all the riot, the racism whatever, we found love… We found a space that we could feel relaxed in”

Brown explains that in the 1970s the house party was the only option for many Black youth in London, the 1980s brought club nights but not everyone gravitated towards it. With friends, Brown formed Mighty Three Hi-Fi, a sound system that played in and around his local area of South London. Brown adds, “in a blues or a hall people were less judgmental”, they had a “raw” sound that you could not get in a club and had more opportunity to emcee. The house party, community centre or shubeen held the vibe of “rub a dub”. He goes on to say that if the dance was rubbish or finished too early “there was always a backup place that might run six nights of the week”. Brown describes the shubeen as a dark space, sometimes difficult to navigate and that it could feel like a scene out of Indiana Jones just trying to find a space on the wall. That you would wait for someone to light a cigarette to catch a glimpse of the person that you’re dancing with. “In the face of all the riot, the racism whatever, we found love… We found a space that we could feel relaxed in.”

“Normalise reggae music”

Brown’s (The) Lovers Rock Exhibition is the first of its kind. It offers a clear and concise unfolding of the scene that was experienced by a new generation. The multitude of Black people especially women pertinent to the genre became the blueprint for the era, together through self-reliance they marked the juncture. Brown describes the exhibition’s success and challenges considering RFUK’s mission “promoting & facilitating reggae artists & musicians in the UK”. Along with this work Brown launched a series of initiatives that would celebrate reggae contributors of past and present and strengthen the ambition to “normalise reggae music”. In a discussion about the re/visioning of the work being done at RFUK, Brown says, “the beginning of this was to raise awareness of Black British contributors to reggae culture”. Since then, the organisation has worked effectively towards integrating reggae culture with peoples’ everyday lives. In 2019 they launched their first Black History Month (BLM) campaign, it was called Gone to Soon.

About the Author:

Yassmin V. Foster is a researcher, artist, academic and sound (system) woman based in London, UK. US. She is a Stuart Hall Doctoral Research Candidate at Goldsmiths University. Yassmin champions interdisciplinary, cross-cultural and multi art-form collaborative journeys, whilst advocating for dance as intangible cultural heritage.