The Super-Picós of Cartagena

As the foundation of popular music culture in the Colombian Caribbean, picós occupy diverse spaces within the local music industry. While the traditional turbo format remains alive and vibrant, some picós have steadily evolved over the decades—from handmade setups lighting up family celebrations to state-of-the-art technological superstructures capable of entertaining thousands of devoted followers. In their ongoing pursuit of exclusive music, many have also transformed into full-fledged music production companies.

As a preview of his ongoing research, this week’s blog post by Jorge Giraldo Barbosa focuses on two of the most renowned “super-picós” from the city of Cartagena: El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha.

by Jorge Enrique Giraldo Barbosa

Introduction

This blog is a heartfelt recognition of the effort, creativity, and talent that sustain the picó industry in the Colombian Caribbean. I will use the city of Cartagena as an example, focusing on two major picós within the champeta genre, in terms of both their physical sound system and the music production output : El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha.

To better understand the relevance of these picós, I conducted brief street surveys and attended picó dances in Cartagena, asking attendees and passersby: What do you like most about El Imperio or El Rey de Rocha? I collected 25 illuminating responses to this simple question.

Additionally, I conducted in-depth interviews with Harold Sarmiento, sound technician for El Imperio, and Luis Marín Burgos, general director of El Rey de Rocha.

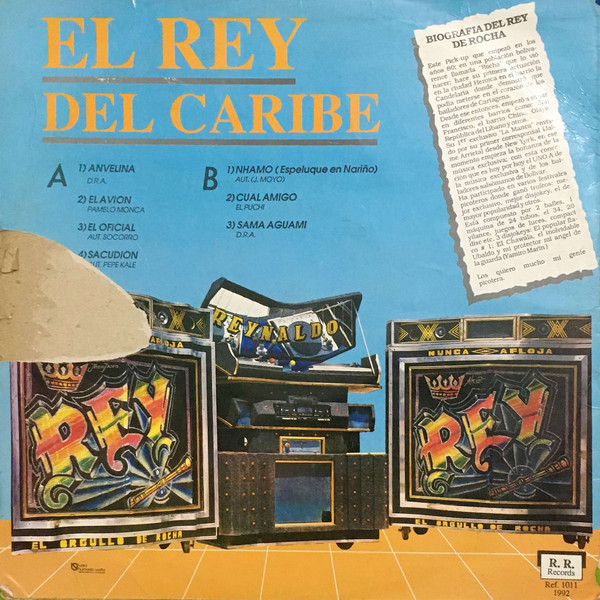

Picó El Rey de Rocha setup.

What is a super picó?

It’s important to clarify that El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha are not the only picós in Cartagena or the region. However, they are among the few that have achieved the status of súper picó, according to the following classification:

“Taking into account the following variables: the social acceptance of the picó (number of followers) and its DJs (renown and musical productions well received by the audience), the frequency of public performances, and its scale within the ‘picó industry’ (organization, hierarchy, and division of labor within the picó), four categories can be identified: a) mini junior, b) junior, c) picó, and d) súper picó”

(Botero, Ochoa, and Pardo, 2011: 88).

The picó category (also known as picós grandes), includes sound systems like Los de la X and El Diferente, which have been gaining prominence in Cartagena’s festive scene and may soon become súper picós. El Géminis de Chamba is well-regarded for being a key platform for champeta talent, in a way similar to the now-defunct El Príncipe. There are also hundreds more in the junior and mini-junior categories spread across the city’s woking class neighborhoods. Overall, this widespread presence testifies to how dynamic and vibrant the picó industry is in Cartagena.

At the regional level, El Skorpión from Barranquilla is unquestionably considered a súper picó due to its legacy, music production output involving DJs and artists, large following, and constant technological innovation. As a company, it is affiliated with CMC Audio, a speaker design and manufacturing company, which gives El Skorpión a kind of corporate brand status that requires it to remain on the cutting edge of tech development. A similar case can be seen in the association between the picó El Boby and the speaker company Ostic Audio. More recently, the picó El Súper Kike has also been gaining recognition in the picó industry and is now recognized as a super picó in the city of Barranquilla.

It is in these two cities—Cartagena and Barranquilla—that the súper picó category is more established. These sound systems manage robust technical and technological capacity, produce influential champeta music, feature well-known DJs, and have a sophisticated organizational structure. They are highly active, performing in urban areas as well as at town fairs and festivals across the Colombian Caribbean. They also play in major cities like Medellín and Bogotá, where there is a strong niche of picó followers. Moreover, they perform abroad, extending the influence of champeta music on an international level. While I was conducting the research, the picó El Rey de Rocha was on tour in Venezuela, performing toques (live shows) in the main cities of the neighboring country.

El Rey De Rocha Venezuela gig poster.

El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha: an overview

From a business perspective, both El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha can be understood as family-run companies. In fact, the owners of both picós are first-degree relatives belonging to the Iriarte Arias family.

El Rey de Rocha dates back to 1985, originating in the town of Rocha in the municipality of Arjona, Bolívar Department. In 1986, the picó was reconfigured and moved to Cartagena, where it quickly consolidated its status as the most influential picó for the champeta genre. [1] Its organizational base revolves around its owner, Ángela Arias, known as “La Niña,” and her seven children: Leonardo, Donaldo, Ubaldo, Aroldo, Arnaldo, Kelly, and Noraldo Iriarte Arias. The latter became the leading DJ and ‘hype man’ (animador) of El Rey de Rocha under the stage name DJ Chawala, gaining massive popularity for his charisma and versatility, as well as for the camaraderie he cultivated with pioneering champeta musicians such as Los Hermanos Hernández, Rafael Chavez (from the group Kussima), Papo Man, and Mr. Blak, among others.

“El Rey de Rocha is history, you know what I mean? Ever since I’ve known El Rey de Rocha, people would go for the music — because they had the exclusives. Back in my day — I’m 39 now, born in ’86 — I’ve known El Rey de Rocha for its music. I’m talking about terapia, I’m talking about champeta criolla. […] And there’s another factor: we have the best DJ in history, who is also the creator of champeta criolla, Noraldo Iriarte, El Chawala.”

— Luis Marín Burgos, interview, June 2025.

In 2008, Aroldo Iriarte, known as “El Flaco,” became independent and launched his own picó, El Imperio, which steadily grew until, by the second decade of the 21st century, established itself as a súper picó. It now boasts a strong roster of champeta artists and DJs widely embraced within the scene such as Dj Jader el Tremendo, along with emerging artists like Luister La Voz, Criss & Ronny, Zaider, Koffee El Kafetero, among others.” [2]

Both picós have developed their own distinct brands and styles within the champeta genre, as reflected in the slang identifying the groups of loyal followers: ‘Reynaldistas’ for El Rey de Rocha and ‘Imperialistas’ for El Imperio. As business ventures, they present themselves as music production companies under the names of Organización Musical Rey de Rocha (OMR) and Maxiteca Imperio Producciones (MIP). Within the music business, they serve two main functions: organizing musical events and operating as independent champeta music labels.

The musical capital of these picós is managed through mutual agreements—sometimes formal, sometimes informal—with champeta musicians. While certain artists may have preferred affiliations with El Imperio or El Rey de Rocha, this does not prevent them from recording with either, or even with other picós or recognized or independent record labels. [3]

Early vinyl release (1991) by El Rey de Rocha, curated and vocalised by DJ Chawala.

More stable professional and artistic relationships typically exist with DJs, who form the artistic core of the picó: the sampler DJ (also called the “drummer,” responsible for adding sound effects with samplers) and the ‘hype man’ or animador. Depending on the picó’s financial capacity, multiple individuals in each role may be part of the artist roster.

The hype men DJs hold the greatest prestige for the picó, as they embody its voice. They are responsible for energizing the crowd with emotional chants, promoting the picó’s songs on stage, and delivering an electrifying performance characterized by spontaneity and improvisation. When champeta musicians perform live, the animador supports the performance by chanting and engaging the audience—an essential part of what I have called elsewhere “neighborhood-based and innovation-driven capital (Giraldo 2016). This is done through the use of cobas, a form of shout-out or praise within the lyrics, which creatively incorporate current popular sayings and refer to people, places, and objects from the local champeta scene and picó culture.

The DJ animador also appears in promotional music videos, sometimes even contributing to songwriting. This role positions them as integral artists with a clear identification with the musical capital of their picó. Some of the most recognized DJ animadores today, based on my research interviews with 25 people, are DJ Jader el Tremendo and Darwin DJ for El Imperio; and Papo Iriarte and DJ Chawala for El Rey de Rocha.

To have a feeling of these DJs in action, along with their stage partners (sampler DJs and champeta musicians) and the two picós impressive set up, here are two live concert videos:

The artist staff ensures the musical output of the picó, often under a model of exclusivity. This refers to songs ( “exclusivos”) whose circulation is limited to El Imperio or El Rey de Rocha during their peak, before eventually being released more broadly, either digitally or via radio platforms. The exclusivo format represents a kind of sound selection capital for the picó, fostering a dedicated audience attracted by novelty and the idea of being able to have access to a unique music work. These songs often undergo constant reinterpretation during live shows.

“In this way, the DJ creates variable products in each new interpretation depending on the duration of the espeluque [or perreo, the moment when the track’s instrumental and melodic intensity peaks], how the piece is repeated, and what’s added with electronic drums, piano, or other sound production tools. In other words, just like musicians performing live improvised acoustic music, these works also integrate many types of live sounds performed (often improvised) by the DJ in real-time through electronic devices [and melodic rearrangements introduced by the animador through cobas and new phrases]. These could be considered ‘musical works’ that, since they are not recorded, exist only for the pleasure of the moment.”

(Botero, Ochoa, and Pardo, 2011: 124).

Therefore, the picó session is a constant overflow of creativity and transformation of what is usually conceived as standard sounds—where innovation and reinvention are the norm.

In terms of their technological image—or the visible part of what I refer to as “technological capital” (Giraldo, 2016)— there are some differences between El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha, but both have reached concert-level sound capabilities.

As explained by Harold Sarmiento and Luis Marín Burgos, they each operate with up to 50,000 watts of PA system, delivered through arrays of midrange, bass, and treble speakers. Complementing this setup are the audio amplifiers (known as planta in picó slang), massive video screens, lighting systems, computers, power generators, DJ consoles, and a full stage structure. Altogether, the system forms a superstructure of musical psychedelia up to 14 meters high (including lighting trusses) and 10 meters wide, representing an investment of 1k to 1.5k million Colombian pesos (approximately USD 250,000–375,000).

“Today, El Imperio is a combination of stage presence—what we call “the image”—and the music. A lot is invested in the image, which is the picó’s very setup, the machine: the midrange and bass speakers, the supports, the infrastructure, the DJs’ platform. Maintenance is constant, both before and after each show—maintenance means costs and effort, all to keep the machine up-to-date and gleaming.”

— Harold Sarmiento, interview, May 2025.

Picó El Imperio live show. Source: @elimperiomip

It’s worth noting that what has been described here is the full set up used for large scale live shows—both picós also operate smaller setups for neighborhood events (known as KZ or caseta).

Depending on the event size, a crew is required. As companies, these picós can employ up to 35 people for live shows, including sound technicians, stagehands, DJs (samplers and drummers), logistics and security staff, truck rivers, and administrative personnel. This entails a major logistical and artistic effort.

The result of this effort can be well summarized through the words of former sampler DJ Jesús David Márquez, a 22-year-old who still dreams of pursuing an artistic career through the picós. When asked if he preferred El Rey de Rocha or El Imperio, he noted:

“I wouldn’t say I like one more than the other because both of them have their own thing. They both guapean [show off, boast] with their music, guapean with their structure. They’re both great picós and they represent the city with pride.”

— Jesús David Márquez, interview, June 2025.

The picó parties stimulate the local barrio economy through a circuit of street vendors (selling food and drinks) in and around the event, and generate jobs in logistics, security, and technical support for the staging of these super sound machines. Thus, they play a key socio-economic role. In addition, the drive, effort, and creative energy involved in sustaining a musical genre such as champeta contribute to a path of social development sparked by family-led initiatives, which in turn inspire other families to pursue ventures within the music industry.

Therefore, these two powerful machines—understood as technological structures shaped by human values, with all their flaws and contradictions—stand as examples of resilience and social transformation, with champeta music at their core, shaping identity through sonic creativity.

Notes

[1] See for example: https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/barranquilla/historia-del-pico-el-rey-de-rocha-y-quienes-son-sus-duenos-283824#:~:text=A%20pesar%20de%20que%20para,es%20un%20precursor%20de%20cultura%E2%80%9D.

[2] See of example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dyww3QqQAxA&t=21s.

[3] Similarly, during live shows they collaborate with guest artists from other musical genres, mainly vallenato, salsa, and reggaeton, but the predominant rhythm of El Imperio and El Rey de Rocha remains champeta, which serves as the foundation for their music production.

References

Botero, Carolina, Ana María Ochoa & Mauricio Pardo. 2011. Economías informales en la música de las ciudades de Cartagena, Barranquilla y Santa Marta en Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación Getulio Vargas / IDRC / CDRI / Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario.

Giraldo, Jorge. (2016). Música champeta y africana en el Caribe Colombiano. Revolución y cultura en la verbena y el picó, Córdoba: Observatorio del Caribe Colombiano / Grupo de Etnomusicología Circolo Amerindiano.

About the Author:

Jorge Enrique Giraldo Barbosa is a Caribbean anthropologist and music lover, deeply connected to the picotera culture. His work is oriented towards the anthropology of music and collaboration with Indigenous peoples, mainly from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the department of La Guajira, Colombia.