Sound system in CDMX. From Concept to Practice

The global scope of our project allows us to compare different types of sonic street technologies and their scenes. This week’s blog reports on the ongoing SST Mexico research, mapping out the current spread of reggae sound systems in in Mexico City and its relationship with the pre-existing sonidera scene. This home-grown Mexican sonic street technology was recently granted intangible heritage status by the City Council in what has become an historic milestone in the ongoing struggle for the cultural legitimization of sonic street technologies worldwide. Researcher and regular SST blogger Linette Rivera reports on the SST Mexico effort in building a dialogue between two street cultures that, although formally independent, have a lot to share.

by Linette Rivera

Can the practice – or the concept – of the reggae sound system be included and benefit from the recent declaration of sonidera culture as intangible heritage in Mexico City?

This question was central to the roundtable organized by SST Mexico, held on December 20, 2023, at EL RULE, a renowned cultural hub in the Historic Center of Mexico City. As SST Mexico, our original intention in organizing the event was to kickstart a dialogue between two sonic street technologies cultures that seem to share several points of convergence, although in practice they remain formally separated. The general notion of a ‘sound system’ as the set of equipment required to play recorded music to a crowd is apparently very open, both musically and technologically. However, here in Mexico, as soon as other rhythms and genres which do not belong to a sonic tradition based on cumbia, guaracha and salsa are included, the question becomes imperative.

Bass speaker painting © Thunder of Tlalok sound system

The same question also reveals that, despite the recent declaration of heritage, a clear definition of sonidero does not appear in the dictionary nor in the official list of the guilds and trades of Mexico City. According to the testimony of several sonideros interviewed within the framework of the SST Mexico project, this generates administrative obstacles by offering pretexts to the mayor’s office to refuse to issue permits to sonideros to play in the public space of Mexico City. In other words, despite the heritage declaration, the complaint of the sonidera community remains the same: the inefficiency and lack of clarity in bureaucratic procedures to request the permits that they need to be able to work on the streets.

In the conversation, Oscar Elizalde from Sonido Casanova extended his reflections to the meaning of the word ‘sonidero’ by putting his own approach to reggae culture into perspective. Elizalde assured that he knew about reggae music, but he was unaware of the Jamaican concept of sound system, let alone its contemporary adoption and ongoing evolution in CDMX. According to his story, the main contact between himself as a sonidero and reggae music was provided by the band UB40, whose albums he used to play as background music at the beginning of his tropical sessions.

SST Roundtable at El Rule, December 2023 © El Rule

Enrique Urbina from Afrikan Blood Sound System moderated and participated in the discussion, elaborating on the ethnic and music relationship between these two SST cultures and the marginalization in which they both operate. In the same way, Yasodari Sánchez, a visual artist and researcher working on sonidera culture in Monterrey, Nuevo León, presented a short video on sonidera culture in La Independencia barrio, as well as reporting on her own research.

Sound Systems in Mexico

The process of adoption of the reggae sound system as a specific sonic street technology culture in Mexico has gone through a long journey. In the mid-90s, when the sonidera culture was at its peak, the spread of reggae music across the country introduced the term ‘sound system’ to Mexico. This was adopted by the early reggae pioneers in Mexico City to describe themselves as collectives of music collectors and selectors albeit usually not owning the actual set of equipment. Although Mexico is the birthplace of sonidera culture, the use of the word ’sound system’ sounded (and to some extent still sounds) fresh and self-describing. But besides distinguishing individual trajectories and nomenclature, the main point emerging from the discussion was the cultural value of these two sonic traditions, both sharing the love for the music and the importance of holding dances in public spaces as central elements.

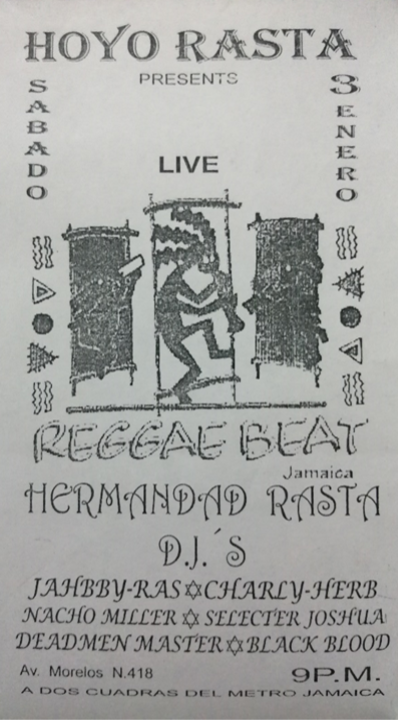

By the end of the 1990s, the rhythm of reggae music as an alternative genre captivated the Mexican audience and was accepted across the country. In the Mexican sociolect of reggae, the term ‘sound system’ was related for several years to the practice of dissemination, collection and production of music rather than to the ownership or building of actual equipment. Hailing from Mexico City, the collective Hermandad Rasta (‘Rasta Brotherhood’) pioneered reggae music parties which were responsible for several generations of reggae fans in town. In their early days they maintained a nomadic approach, hiring out different patios or indoor venues to host their Saturday night dances for several years. The music was initially played through tape cassettes, and the sessions sometimes included performances of Mexican reggae bands such as Antidoping or Rastrillos. Reggae music was not only spread to the public during these parties. It was also marketed by Jahby, a member of the collective, who used to sell duplicated tape cassettes at the Chopo flea market. Later, duplicated CDs took over cassettes and remained a staple until digital music took hold. In those years, the sound system also adventurously played in open-air public spaces.

Flyer for a Hermandad Rasta session, 1990s, CDMX © Linette Rivera

In the mid-2000s, Mexicans with a specific interest in sound system culture such as Enrique Urbina started to visit London. It is at this stage that the concept of a ‘sound system’ returned to Mexico, this time more associated with a specific cultural and technological practice. Putting “the word into action” implied learning the technical knowledge related to sound technologies, ranging from carpentry to equipment design, from engineering to manufacturing, and including repairing and modifying pieces of equipment. The adaptation and, later, generation of a local variety of sound system culture in Mexico thus took off from a recently discovered practice which was mimetically raised under a political discourse of pacification and coexistence, and under a logic of institutionalized cultural management.

From my own positioning as a fan and researcher, I have been able to witness the evolution of the sound system concept in CDMX, and today I can find a meta-semantic relationship with the sonidera culture. In general terms, I believe that these two different types of sonic street technologies can be understood as technologies of remembrance, which diachronically generate border-crossing sonic environments and produce atmospheres for dancing and coexistence. Following Jurij Lotman’s definition, the sound system ca be conceived as a semiosphere, that is, a space of meaning. [1]

Osiris sound system, Iztapalapa, CDMX © Osiris sound system

The semiosphere of the sound system acts as a mobile device with its own structure. Actions such as transporting, unloading and operating the sound are steps towards creating a setting where the attendees can be welcomed. In this respect, I agree with what Julian Henriques describes as sonic bodies: that constituent corporality that delimits a space and creates a special atmosphere where the bass frequencies, characteristic of reggae, resonate in each session.

¨Sonic bodies are the flesh and blood of sound system crew and ¨crowd¨ as the dancehall audience is known. They are single and multiple. They are social as with institution as with the sound system session at the center of the dancehall scene¨ [2]

Afrikan blood sound system playing at El Rule, July 2023, CDMX © Linette Rivera

The sound system can be understood as a mobile device which, session by session, perpetuates memories through sound and lyrics. The cultural memory that makes up this institution is undoubtedly an example of cultural resistance, where both Jamaican wisdom and techniques continuously evoke the deep memories of Black slavery, the call for universal love or the celebration of social struggle. This rooted memory is transmitted through the frequencies of sound across space and time in a panchronic way, recreating new forms of interpretation, without losing its original meaning. I argue that it is through this musical practice and sonic dissemination that both sonideros and sound systems achieve a similar interpretation of the use of sound technologies which evolves in parallel forms of repurposing.

Nowadays, the younger generation build their own sound systems in Mexico. Some operators have drawn inspiration for their practice from the sonidera culture due to their own family legacy which they have then oriented towards the Jamaican-British model. The spread of reggae and its subgenres such as dub continues to be enhanced by Mexican sound systems. From this border, to return to Iuri Lotman’s conception [3], these have been reinterpreted through a specific Mexican angle deeply infused with the sonidera influence.

Sistema de sonido El Venado Xochimilco, CDMX © El Venado

The similarities that sonideros and sound systems share in their respective contexts are those of cultural forms that were born in the margins and have gradually moved towards the center. In the case of the sonideros, it has been a marginal culture from the very beginning. Their sessions started to be hosted in the barrios and from there they have slowly appropriated portions of the public space, one of the most coveted dance floors that, despite the ongoing challenges, has been firmly held over several decades. Therefore, it is important to open spaces of collective discussion to rethink both sonideros and sound systems, two cultural movements whose practices are not as distant from each other. It also remains urgent to monitor closely both cultures and their ongoing evolution to deepen the understanding of the wider implications of these sonic street technologies in both symbolic and political terms.

About the author:

Linette Rivera is a student of Linguistics at the National School of Anthropology and History in Mexico City and part of the SST Mexico research team. She is interested in sound system cultures and reggae music.

References

[1] Jurij M. Lotman. La semiosfera I . Semiotica de la Cultura y el Texto. Ediciones Catedra, S.A., 1996, España, p. 20.

[2] Julian Henriques. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing. London: Continuum, 2011.

[3] Lotman, op. cit. p. 13