Researching with Purpose in Urabá, Colombia Pt. 2

This blog continues the report on the ongoing SST research in Urabá, Colombia, which has also been supported by Goldsmiths as a possible Impact Case Study. [1] Producing and commissioning short films is part of the SST research methodology. In the same way, the screening can also be part of the research process. Screening the research film on Urabá Sound System collective not only presented opportunities for further research and feedback, but also allowed to maximize the impact potential of the case study. Dr Brian D’Aquino tells us about the first leg of the screening tour for Sonando con Proposito.

This blog is also available in Spanish at this link.

by Brian D’Aquino

The support from Urabá Sound System and the trust of the local picó community allowed a successful shooting of the research documentary Sonando con Proposito on Urabá’s picotera culture (as discussed in this previous blog). The great feedback prompted SST to elaborate a strategy to ensure that the documentary could serve the collective’s aims in the most effective way.

Hosting a premiere of the research film for the communities that contributed to the film is certainly a good practice (see for example this blog). Besides consolidating existing relationships and offering feedback on the ongoing work, this can also provide a chance for a unique shift in perspective. Meeting their on-screen persona as part of a wider narrative is usually a powerful experience for the practitioners. Even more so for the researchers, who can appreciate firsthand how their work is seen by external eyes – the most well-meaning ones. Ideally, this (ex)change in perspective can mark the beginning of a new stage in the research.

Urabá Sound System collective founders, left to right: Rafael Paz Perea, Miladis Córdoba Rivas, Willinton Albornoz Quejada, and film director Ricardo Vega. Image: USS.

Spending time with the collective’s leaders Miladis Cordoba, Willinton Albornoz and Rafael Paz during the filming days allowed me to better figure out how Urabá Sound System’s ambitions are articulated. Pushing for the picó to be recognized as a dignified culture and business in Urabá is a process made of several intermediate steps, reflecting both the depth of the collective’s roots in the local context and the breadth of their vision. This wider ambition can be unpacked into three stages of intervention, each with its own scope, timeline, and related counterparts.

- The short-term, local objective is to end stigmatization and overcome the ban on picó dances in Urabá by liaising with local authorities and involving owners, fans and young people in the peacebuilding process.

- The mid-term aim is to build connections with universities, cultural institutions, and other practitioners to break Urabá ’s cultural isolation and make the richness of local picó culture recognized on a national scale.

- The ultimate scope is the heritage declaration for Colombian picotera culture, including Urabá’s, nationally and eventually internationally (UNESCO). This is a long-term objective requiring strong national and international support and a robust archive to support the case.

Such an overarching agenda encouraged SST to be more ambitious with the film premiere. The project proposed Urabá Sound System a screening tour across Colombia to maximize the impact of the film and build engagement with different audiences to meet all three scopes of action. The collective accepted our proposal enthusiastically and we both started to reach out to possible partners. Once again Goldsmiths provided the needed financial support with a second successful Impact grant application, thus enabling the collective to travel to lead the discussions.

After a few months of editing, preparations, and a successful screening at the Global Reggae Conference in Jamaica with online Q&A, by the end of February 2024 Sonando con Proposito was ready to hit the road. The travelling crew was made up of the three collective leaders Miladis, Willinton, and Rafa, film director and El Gran Latido owner Ricardo Vega, and me.

Screening in Apartadó

The tour kicked off with two screenings in Apartadó and Turbo, the two cities where the film was shot. These events contributed to the ongoing local process that the collective has been leading since 2021. In terms of the expected impact, they were specifically aimed at consolidating the collective’s local recognition: building further engagement with the picoteros and fans, especially youngsters, and supporting their position in the ongoing institutional negotiations.

Miladis coordinating refreshment delivery for the Apartado screening. Image: B. D’Aquino

Expectations and curiosity among the community about the film were high. Since the shooting, the collective had also made substantial progress on the ground by launching Asopickups, the official trade association for Urabá picó owners, with Rafael Paz as president, whose reach out the screenings also helped to strengthen.

Logo for Asopickups Uraba (president: Rafael Paz Perea)

The Apartadó screening was held on the 29th of February at Casa de la Cultura (‘House of Culture’). This municipal venue is located in Plazuleta Rosalba Zapata, Barrio Obrero, a marginalized neighbourhood where the 1994 Chinita massacre took place. The event was especially targeted at local young people and teenagers for whom Casa de la Cultura provides cultural activities and mentorship. Overall, the event attracted around one hundred people, with a massive presence of minors, including those under “special protection.” Miladis explains:

Young people under ‘special protection’, also incorrectly called ‘gang members’…. are children who are neither in school nor have a job but are on the streets all the time, taking part in conflicts around invisible borders between neighborhoods… They confront each other with machetes, and some have been injured and killed…

Willinton adds:

They are monitored by the mayor’s office and the police who try to channel their energies and skills into something positive… They were summoned [at the event] by these entities also because they represent most of the crowd, and the main cause of incidents, at the picó parties. So, it was important that they were there. What I felt is that they still don’t have a very deep understanding of what is going on [in the picotero movement], but it was an opportunity to start a dialogue with them.

Miladis introducing the film in Apartadó. Image: B. D’Aquino

The Police attending the screening in Apartadó. Image: B. D’Aquino

The discussion, led by Urabá Sound System, also involved representatives from The Peace Unit, the Peace Lab, the mayor’s office, community leaders and local picoteros. It focused on the positive impact of picó culture on young people and the community at large and provided a chance to the collective to report on recent achievements. Willinton explained:

We wanted to show the film to the people who have contributed to the process so far… The purpose was also to give opportunities to young people to connect [to the process] and to open a conversation after the projection about what should come next.

Another important topic was the stigmatization, particularly marked in Apartadó where in 1994 35 people were killed and legendary picó El Gran Juancho was burned down in what became known as the Chinita massacre. Since then, sound systems have been unfairly associated with violence and consequently prohibited. As Miladis put it:

By hearing from the protagonists and followers [of picó culture] it was possible to upturn the discourse surrounding the picó, allowing to de-signify and re-signify it… Sound system owners offered attendees a context about where the stigma comes from.

Sonando con Proposito screening again outdoor with picó La Nueva Ley. Image: B. D’Aquino

The event was supported by La Nueva Ley, a leading picó from Apartadó. Owner Dayner Becerra, one of the film’s contributors was also on the panel. One stack of their set was stringed up outside the premises playing music before and after the screening to attract the younger crowd. The venue location in a challenging area persuaded the collective to respect an early 6pm curfew. The event was successful, attracting way more young people than was expected and consolidating the collective’s position with both the authorities and the community. Willinton notes that:

New municipal officials went on duties on January 1st. So, this was our first contact with them, in a scenario controlled by us, where they were able to understand what we are working on and the meaning of it…

The community is often very skeptical of this type of process. When we started, people did not believe that we would have sustained the process until now, so the fact that we return [to Apartadó] and that it continues to have events after the change of administration, it is like a great step.

Anonymous comments from the audience were also overall very encouraging, such as:

Many people do not know the history. Thanks to this, you can learn a lot straight from the practitioners.

The extent of the research was incredible, it covered a lot of the different areas and history of pico culture.

[The event] summoned many practitioners and young people in peace and coexistence.

[The film] tells you about the real history without stigmatization, it gives you another perspective.

[The event] prompts a lot of reflections about the value [of the culture] for a place like this.

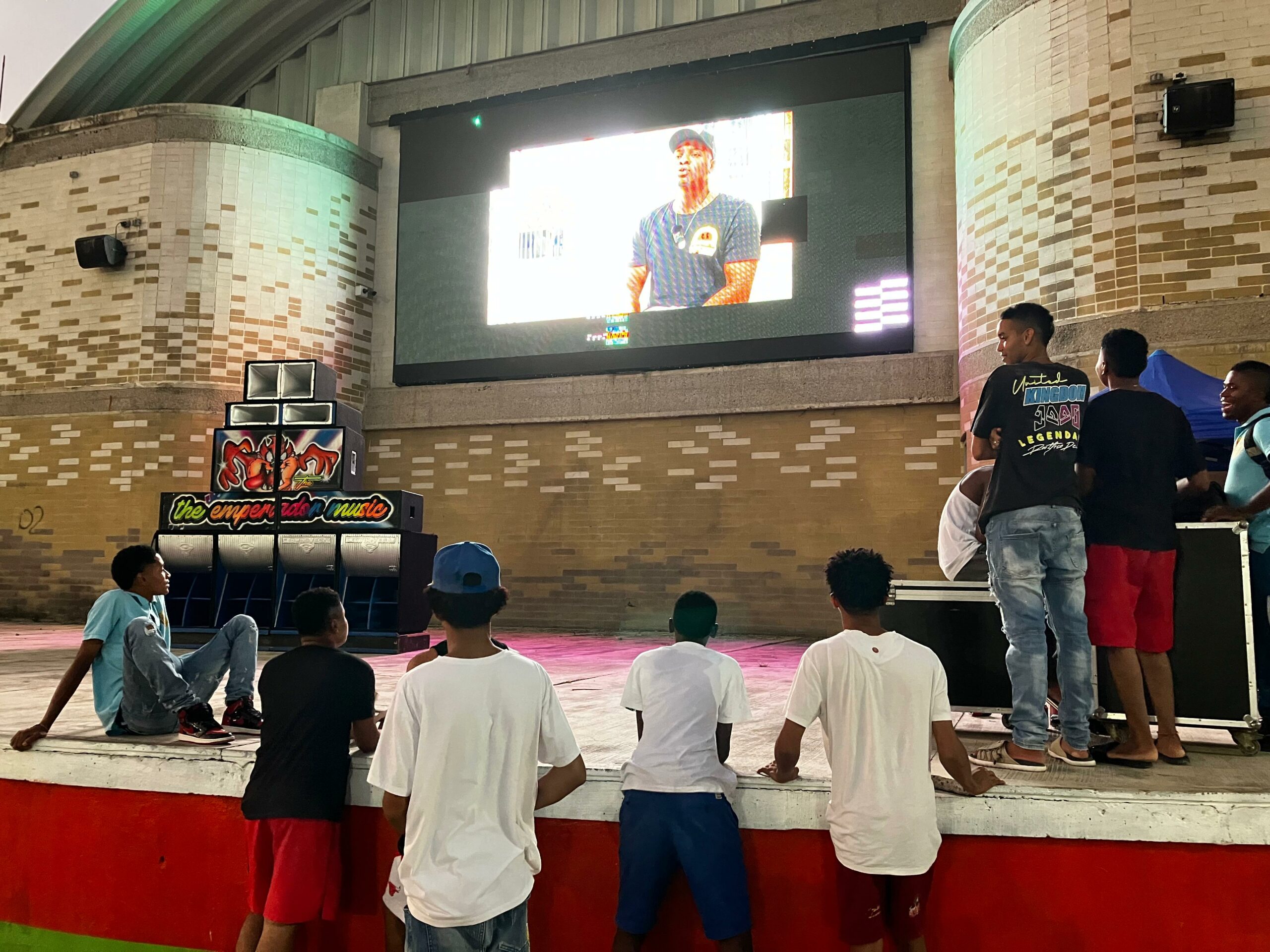

Screening in Turbo

On the 1st of March we moved to Turbo, half an hour’s drive from Apartadó. Thanks to its large port, Turbo is a trade center and the most populated city in Urabá, as well as the region’s undisputed picó capital. The Turbo screening took place at La Bombonera, an open-air court which boosted the reach out of the event, as Rafa explains:

[La Bombonera] is a well-known place visited by families and many people. When they saw something was happening, they came to check what was going on and found out it was a documentary about the history and the memory of picotera culture in Urabá.

Miladis introducing the film in Turbo. Image: B. D’Aquino

The event enlisted the endorsement of the University of Antioquia and the Turbo municipality, with major picó El Firu DJ providing logistical support with a projection screen and sound equipment. The accompanying sound system was El Super Yilier. The panel included several practitioners who appear in the film, such as el Firu DJ, veteran picó painter Barranquilla, Gullier Mesa from El Gran Juancho and his brother, recording artist Betoman, among others. There were also students and representatives from the University of Antioquia, and two delegates from the Government Secretariat. Miladis reflects:

I believe [the event] was a very good opportunity not only to promote the issue of permits and the facilitation of what picoteros propose, but also to strengthen the relationship between municipal administration, community leaders and picoteros.

Picó El Super Ylier setting up. Image: B. D’Aquino

The event followed a mid-February meeting with the new mayor who had completely clamped down permits issue again after his election. The presence of the two delegates from the Government Secretariat at the screening allowed the collective to reiterate their demands and push for a new decree to reflect the ongoing negotiations. As will notes:

We had already spoken to the mayor and the Government Secretariat, who are the top-ranking figures, but we had not yet met the delegates who are in charge of writing the decree, who need the knowledge of the process we are carrying on, they need to know its meaning in depth.

Urabá Sound System collective associates also watched the film for the first time. Their comments were positive about both the documentary and the event:

They saw that we are not alone, and they are beginning to treat us with respect.

It was illuminating and wonderful.

Thanks to this event we saw that we have a lot of power to use!

It made claer that the sound system is a contributor to peace.

Besides those contributing to the discussion there were dozens of other attendees, mostly teenagers and children who remained at the back of the court or sat on their own bikes. Their reception of the film was also very positive, as expressed in the feedback questionnaires they were mostly happy to fill out. Interestingly, they all considered themselves as part of the picotera community, as per questionnaire’s opening question. The extent of the younger crowd’s engagement with a is a powerful and an almost unique feature of the Urabá scene, as we would have learned afterwards.

Discussion in Turbo after the screening. Image: B. D’Aquino

Group picture after the Turbo event. Left to right: Ricardo Vega, Miladis Cordoba, Edwin Cuesta (El Firu DJ), Heriberto Alvarez ‘Cartucho’, Guiller Mesa (El Gran Juancho), Rafael Paz, Alberto Mesa Castillo ‘Betoman’, Barranquilla, Brian D’Aquino, Wilder Lemus Chavera, Willinton Albornoz. Image: USS.

Returning to Urabá ten months after the shooting was a powerful experience. Witnessing how the collective has continued to push its objective was especially noticeable. I also could see firsthand the positive contribution that the documentary has made – even before the screenings took place: by It generated generating expectations in the community, it helped the collective to keep attention high even during the change in local administration and the consequent ban on dances.

This energy cannot be taken for granted. Research alone can only trigger short-term responses within the sonic street technologies scenes. In this case, the commitment of Urabá Sound System and their articulated, long term political strategy allowed the film to contribute to a lively and indeed powerful process. The next blog will report on the screenings in Medellin, Barranquilla and Cartagena.

About the author

Brian D’Aquino is Senior Research Assistant for the SST project. He is a researcher, sound system practitioner and music producer.

Notes

[1] Impact Case Studies are a component of the Research Excellence Framework – the assessment of research outputs required of all UK universities, see for example https://impact.ref.ac.uk/casestudies/

[2] REF Case Studies invariably require empirical evidence. In this case, evidence included footage, images, Vox pops and feedback questionnaires.