Futuring a Century of Sound

What does the future hold for sonic street technologies scenes? While we don’t know the answer to this, we do know the intergenerational transmission of the culture is an issue for many scenes around the world. We also know that one of the project’s briefs is to try to find out. Hence the need to develop methodologies for this task. Clare Cooper of the SST Australia team here outlines her futuring methodology – as applied with participants at the 8th Global Reggae Conference (GRC) earlier this year. One other thing with which the project is familiar is how sound is invariably a multi-sensory experience. Cooper’s visualization of futures is a key aspect of her methodology, as you’ll see in what follows. She presents an application of the ‘design timescapes’ visualization that draws on a decade of her design futuring practice to facilitate a visual conversation – a ‘Sonic Timescape’ – that maps key insights, historic shifts, and future projections in real-time.

By Clare Cooper and Natalia Gulbransen-Diaz

Reflecting on the histories of sonic cultures, technologies and impactful performances can be enhanced by a simultaneous process of futuring. Visualising these moments in a ‘design timescape’ (Tomitsch et al 2020, Cooper 2022) helps to open the conversation up to more than just those in the room, and also helps to draw new connections between the contexts and consequences of these significant cultural contributions. By situating key moments in sonic street technology development side by side on a visual, temporal scale we can gain a greater understanding of shared and contrasting sociaopolitical contexts that may have informed technological innovations, but also damaging policy shifts, and gender equality battles in the various translocal scenes. The visualisation of these relationships serves researchers engaged in better understanding their own local story in a global context, but also those from other disciplines seeking to understand the significance of sound, sonic innovations, social change, and informed possible futures.

Design Timescapes

The ‘design timescapes’ futuring method was initially developed during my professional design practice to challenge design students to visualise the relationships between their designs and societal shifts, and encouraging the development of visual argumentation for design proposals and futures-focused thinking. In the field of design, considering the precedents and consequences of a design innovation or intervention is integral to generating a design ethic that respects both our past and future generations (Escobar 2011, Fry 2009). My paper Design Timescapes: Futuring through visual thinking (Cooper 2022) describes the origins and applications of this tool in greater detail, illustrated by visual communication student works based on a live brief in collaboration with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. This paper is a combination of a reflective practitioner piece and photo essay, in that the heart of the offering is the application of the ‘sonic timescape’ itself.

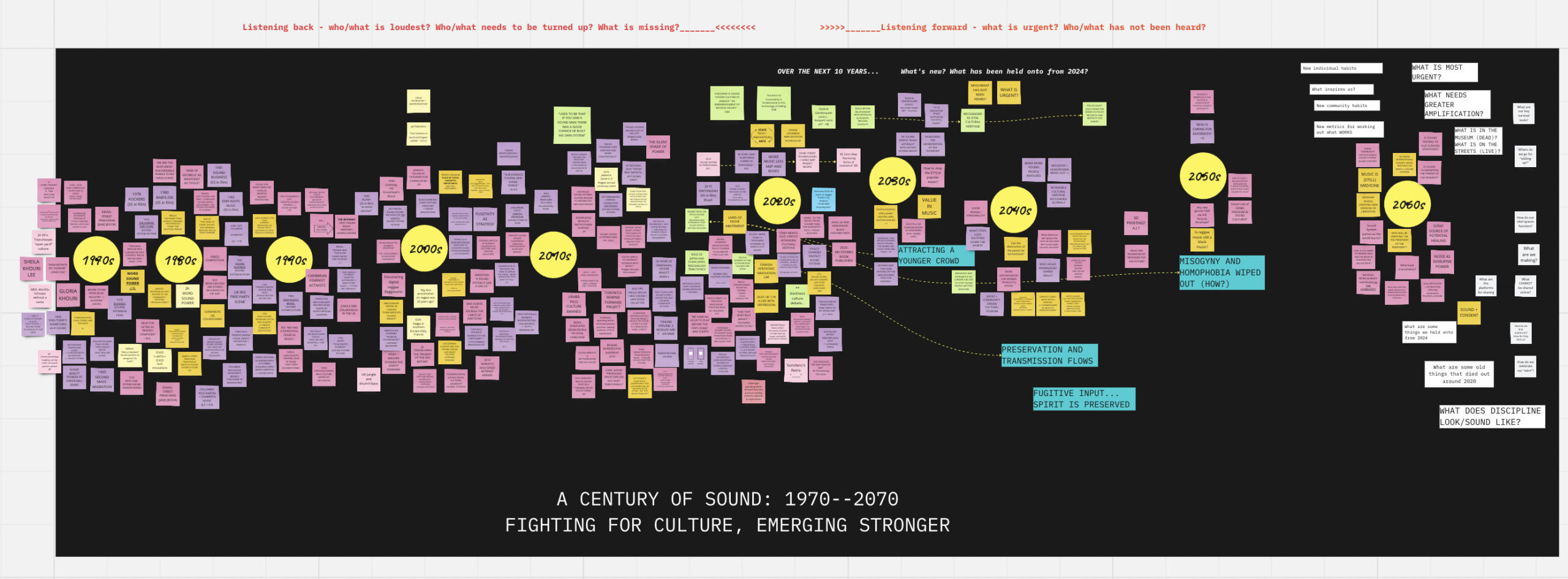

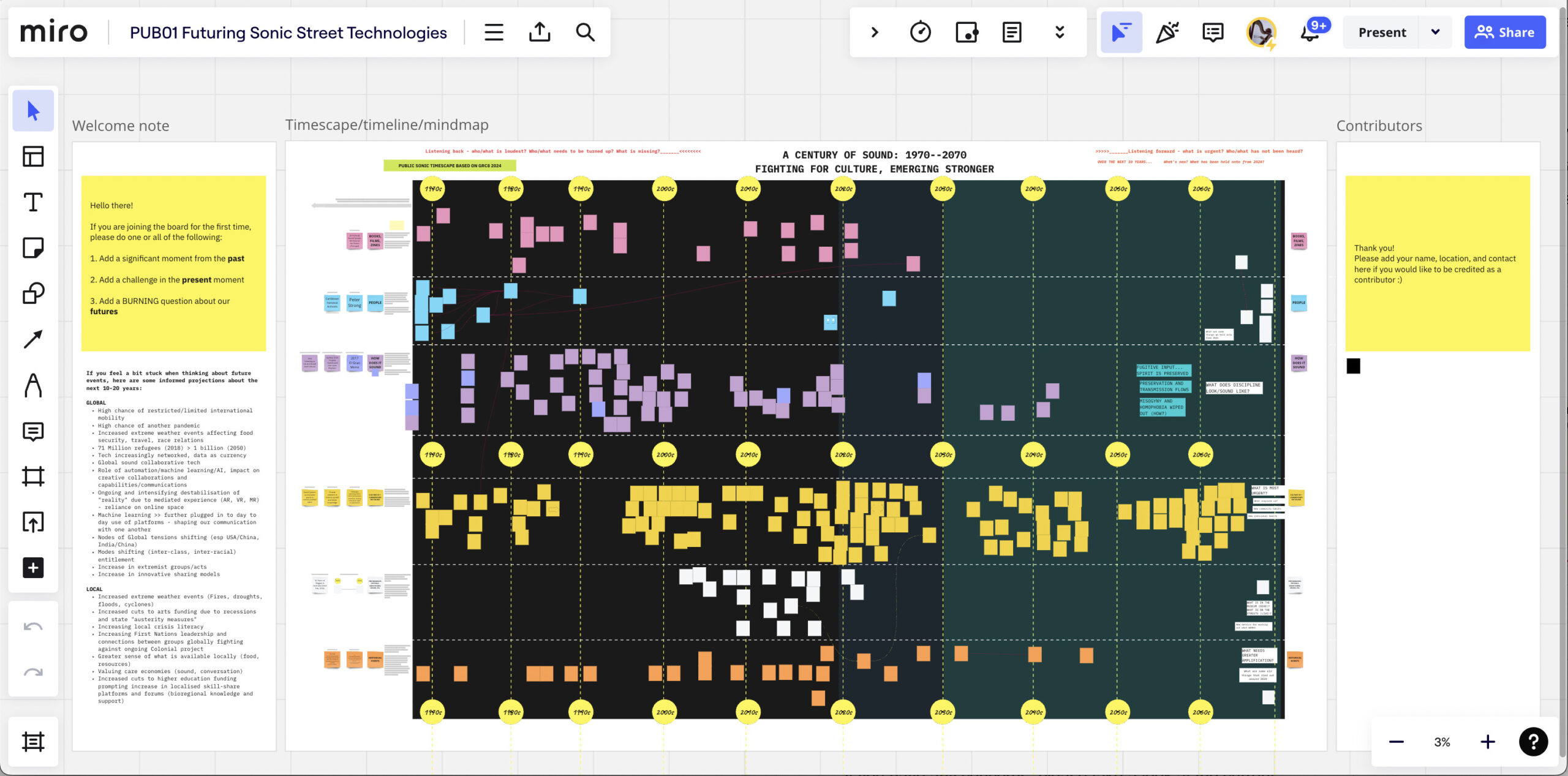

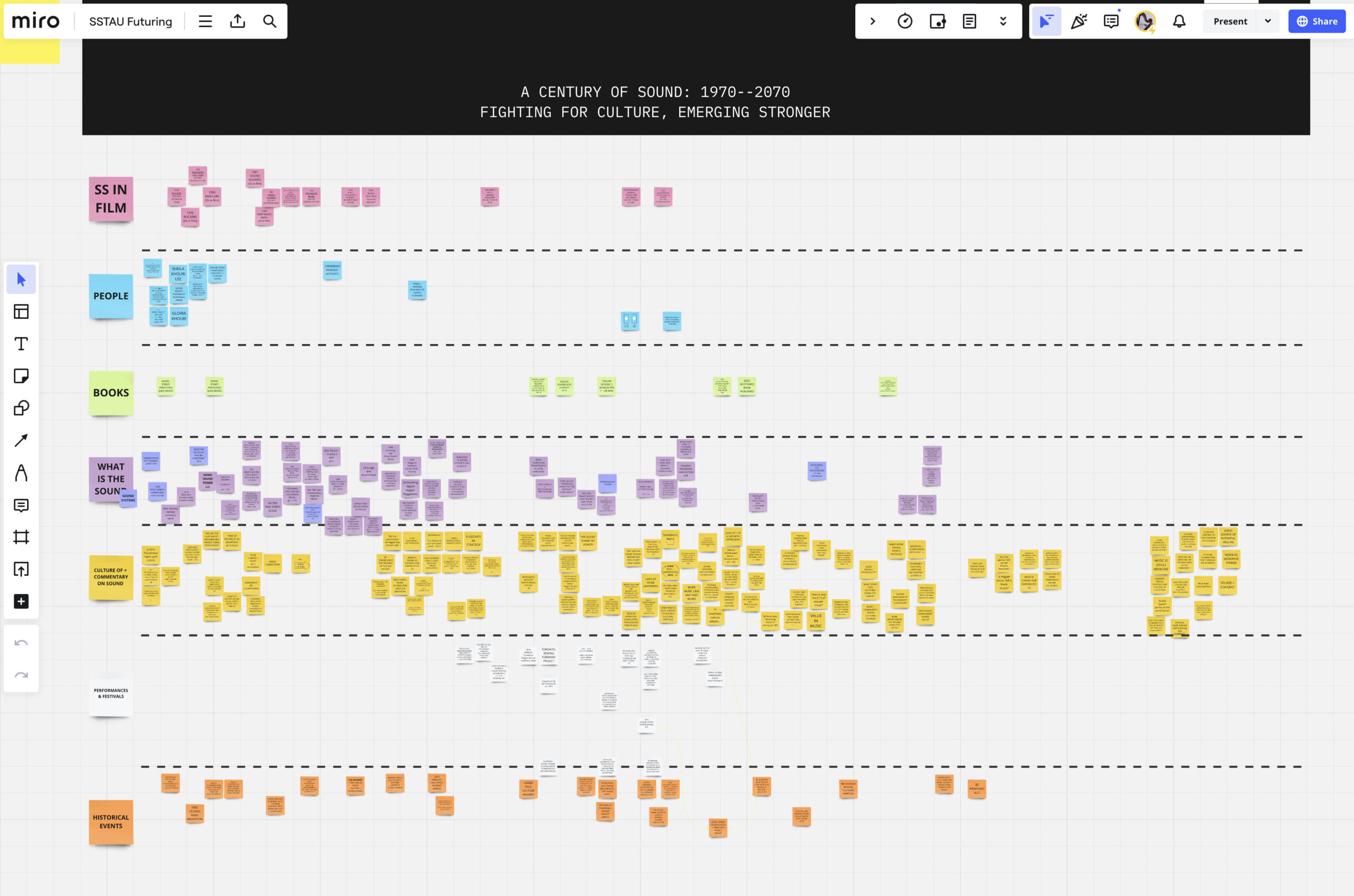

To best position the offering, I will share the methodology, including a working definition of key terms. Readers can choose to either explore the photographs of the physical ‘sonic timescape’ captured at GRC or click through to the digital resource: a digitized and evolving version using the online tool Miro.

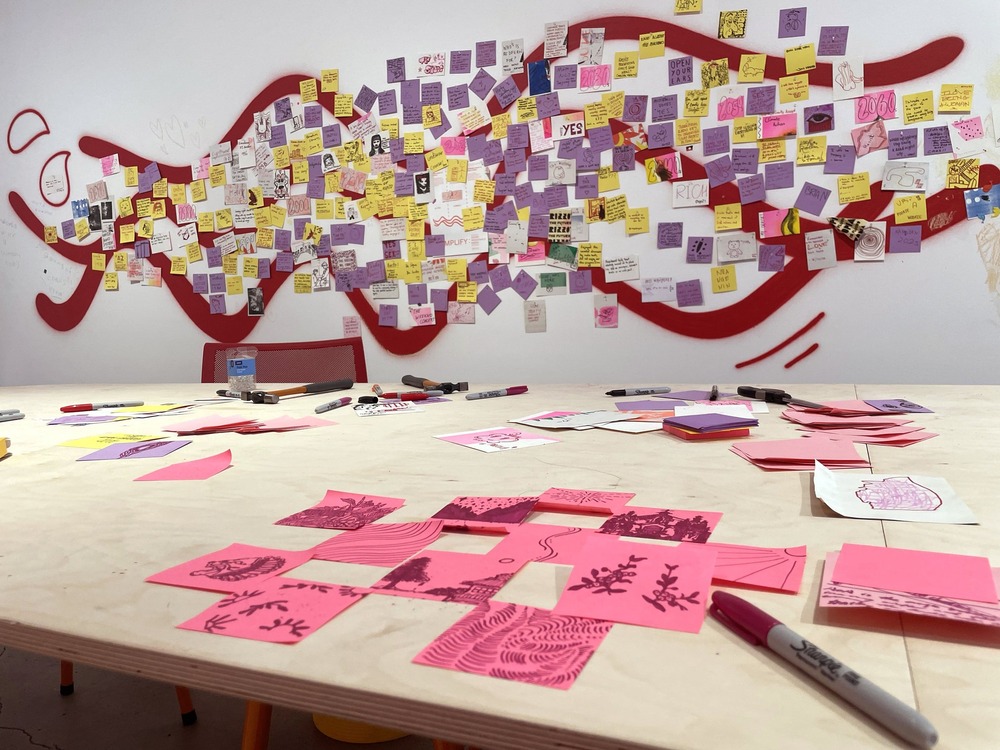

My proposal to GRC was an extension of the first ‘sonic timescape’ that I designed and facilitated as part of an exhibition I co-curated entitled Amplify: Story, Resistance, Radio (see figures 1 and 2). The evolving temporal visualisation was a core component of the exhibition exploring the role of sound and politics in urban spaces, with a focus on sonic activism, the free party scene, and community radio platforms in Australia.

Figure 1 and Figure 2: Author’s own photographs of the first iteration of the Sonic Timescape on the wall of the Amplify Exhibition at Tin Sheds Gallery, The University of Sydney in October 2023.

Methodology

It is necessary to share a working definition of several interdependent key terms and approaches applied in this paper: ‘futuring’ and ‘backcasting’ (both of which have traction in contemporary strategic design), and ‘pendulum futuring’. These definitions draw heavily from the author’s previously published definitions (Cooper 2022):

Futuring

Futuring is best known through the field of futures studies, futurology, or foresight thinking (Cornish 2004, Hoyle 2006, Inayatullah 2008, Fry 2009). It has been used in foresight analysis in the business world for decades (Inayatullah 2008, Jefferson 2012). Futuring is not predicting futures. It combines informed projections with imaginative critical ideas to invite audiences, researchers, organisations, communities, and individuals to think differently about our present obstacles and opportunities. In this case, the process was designed to help those engaging in sonic street technologies to take a step back from current challenges and proactively design steps to change things for the better—not 20 years from now, but from today.

Backcasting

Originally called ‘backwards looking analysis’, backcasting was developed in the 1970s (Lovins 1976) as an alternative planning methodology for electricity supply and demand (Bridger Robinson 1982, Anderson 2001) and has been used widely in futures studies ever since (Boulding and Boulding 1995). Backcasting is the construction of a chain of traceable steps from a proposed future scenario back to the current day (Inayatullah, 2008, 18).

Pendulum Futuring

When inviting people to think about futures beyond the next 3-5 years, I have found it helpful (and sometimes necessary) to give them a ‘run up’—a relative period that they can recognise and chart shifts within. This makes a futuring timeframe of up to 50 years more tangible for participants. I call it pendulum futuring because those engaged in the process are exploring the same amount of time forwards as backwards, creating a kind of non-linear swing to and from futures — in this case, listening 50 years into the history relating to sonic street technologies and 50 years into futures from our current moment in 2024.

Context of GRC and contributions from participants

The GRC conference Chair Sonjah Stanley Niaah, Ph.D. stated in her welcome message:

For this iteration of the conference, we seek to fill a gap in the scholarship and industry mobilisation around sound systems or, more technically, sonic street technologies with the theme – ‘A Century of Sound: Technology, Culture and Performance’. Ultimately, the 2024 edition of the Global Reggae Conference celebrates and investigates the culture and technology of Jamaica’s most famous musical instrument. From Kingston’s streets to the world’s biggest festival stages, the Jamaican-born institution of the sound system has deeply influenced the way music is produced, performed, remixed and enjoyed all over the world. (Stanley Niaah 2024 GRC Conference Programme)

As the lead researcher for the Australian component of the global Sonic Street Technologies project, the 8th Global Reggae Conference was an incredible opportunity for me to gain a greater understanding of common challenges and opportunities for communities, designers, and advocates for sound systems worldwide. The presentation themes ranged from historical accounts of significant figures, styles, family traditions, resisting state violence, music composition, technology and marketing, gender politics, and regional exchange, and took the forms of paper presentations, panel discussions, and an extraordinary film programme. It was only possible to sample sections of each presentation and films for the sonic timescape, but the result is a unique representation of the breadth and depth of issues raised, and possible futures proposed.

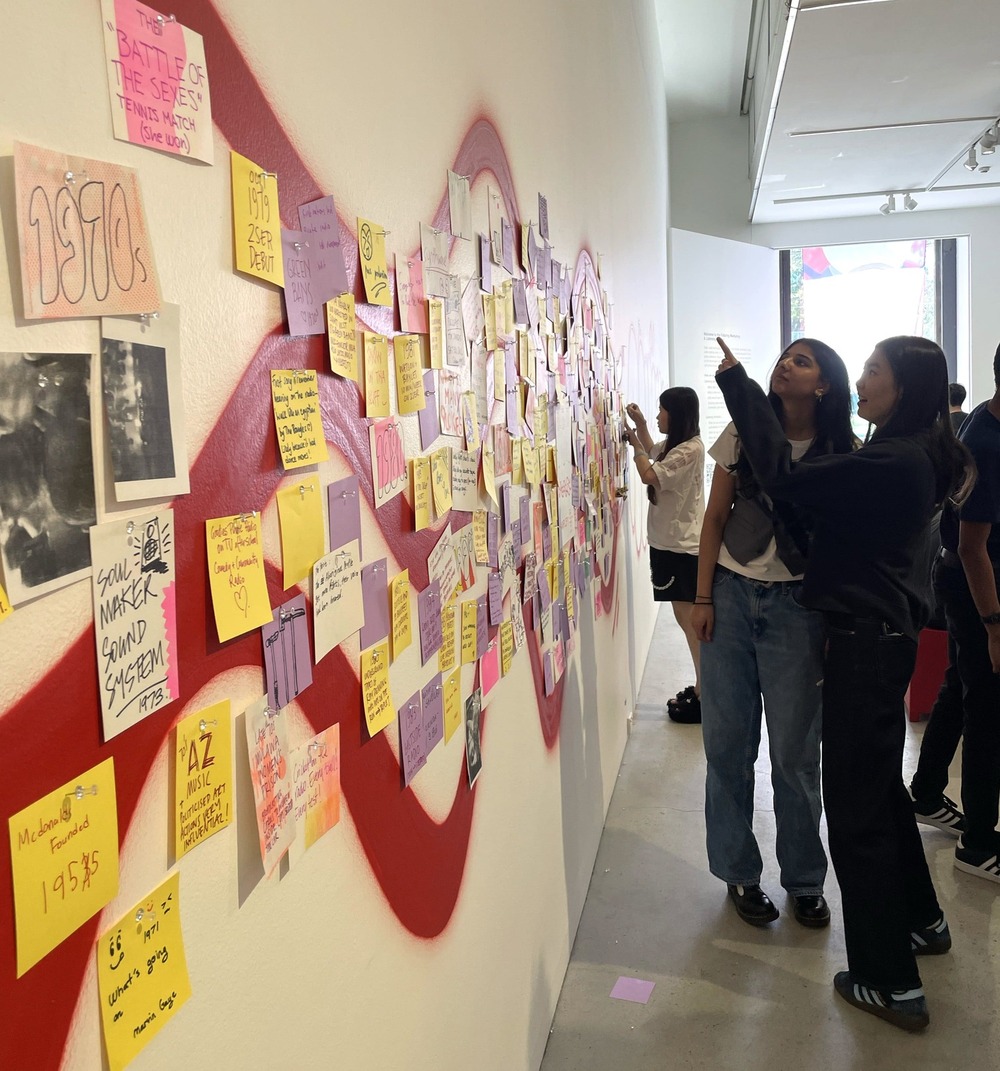

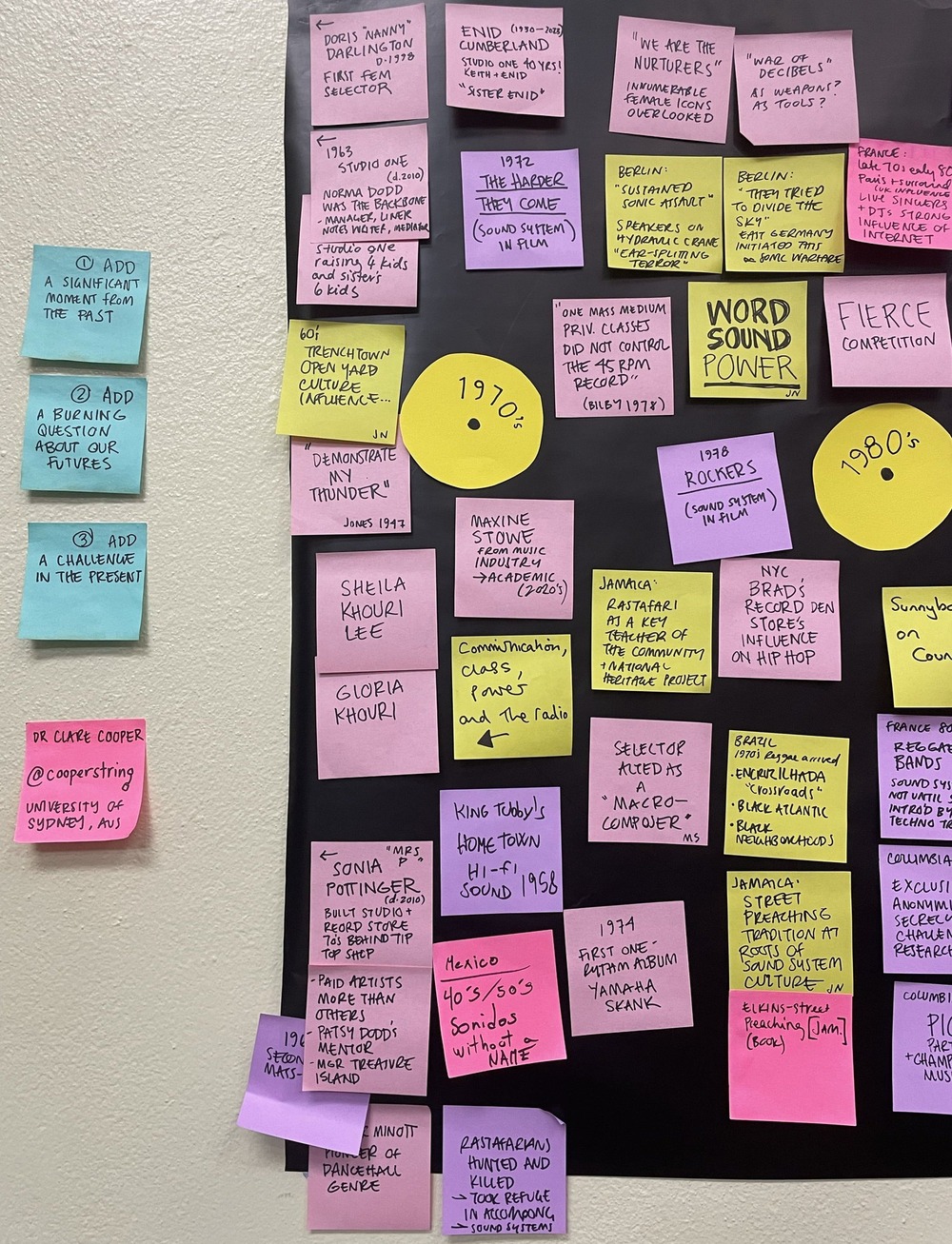

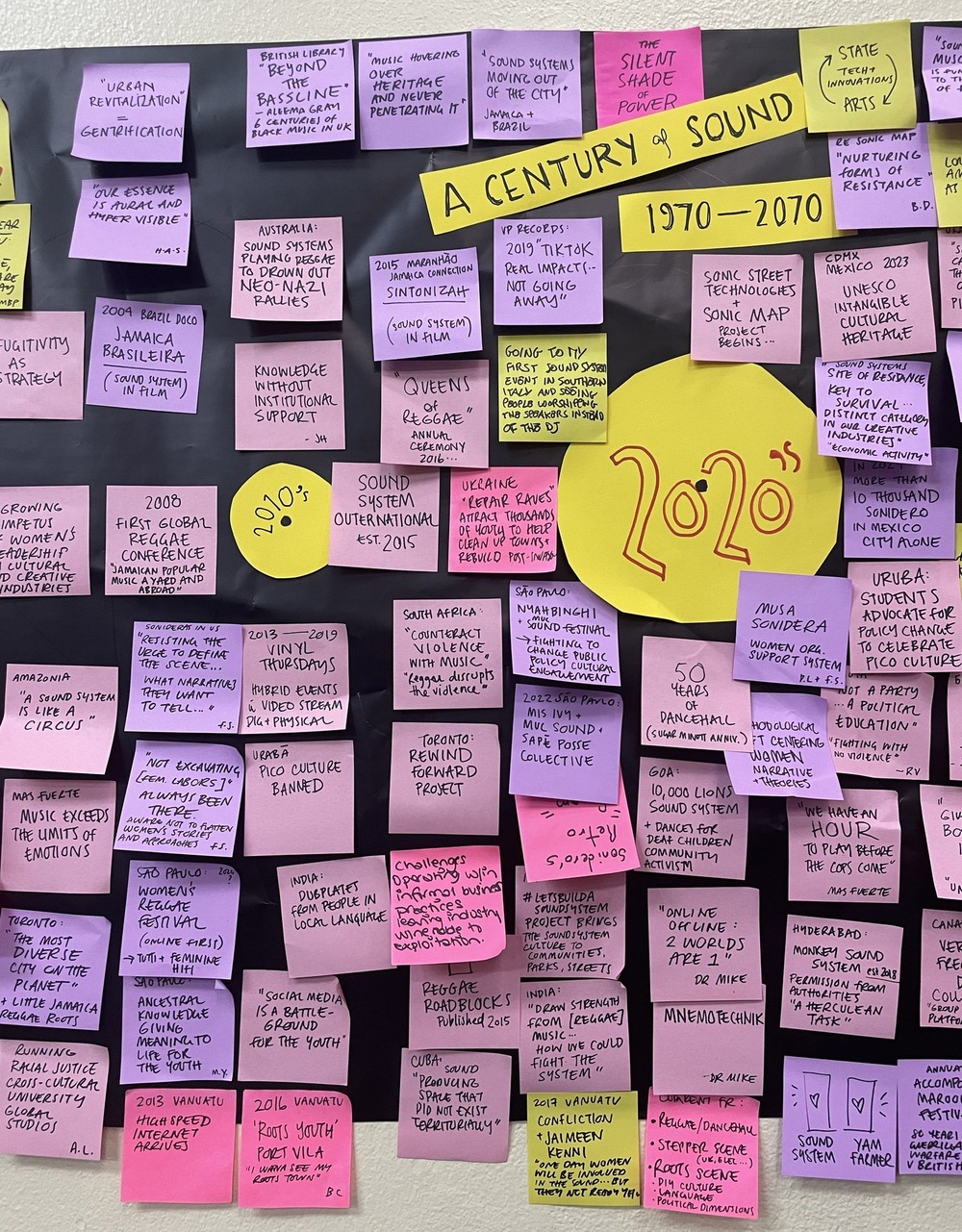

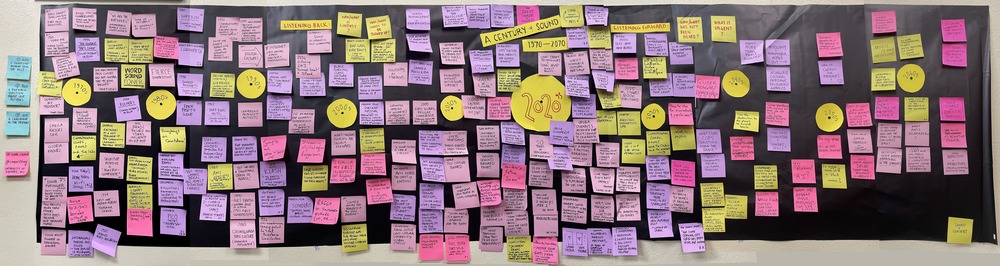

The physical design timescape was installed on a wall in the main conference room at the University of West Indies. I used 4m of shiny black paper and brightly coloured sticky notes and cardboard shapes in the style of vinyl stickers to mark the decades. I acknowledge that the century referred to in the conference title is the century leading to 2024, but my timescape design visualisation focuses on a 100 years pendulum swing from 1960’s to 2020’s to 2060’s to engage participants in the possible futures fed by our rich, intertwined histories.

I presented a short workshop on design futuring during the conference, explaining its application at GRC, and invited participants to contribute. For those who could not attend the workshop, I created a guide on the wall beside the work with a list of 3 prompts:

-

- Add a significant moment from the past

- Add a BURNING question about our futures

- Add a challenge in the present moment

Many of the contributions were based on conference presentation details and were added immediately after each presentation. I captured some direct quotes from presenters who are credited with the quote. The remaining notes are from conference attendees. Readers can view and contribute to the evolving Sonic Timescape on Miro platform1 here: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVKbxRizI=/

Results

Figure 3: First point of contact with the ‘sonic timescape’ (far left side) shows the blue notes with the 3 key prompts. A significant number of the “pre-1970s” posts were from Heather Augustyn’s presentation Studio Sistren: Women at the Controls in Jamaica’s Early Era of Recording, and Maxine Stowe’s presentation A Comparative Overview of the Parallel Sound System careers of Kool Herc and Sugar Minott. Both of these impressive presentations mentioned many significant and often overlooked figures active in the 1960’s, so the ‘century’ extended a little further back to include these important people (many of them women).

Figure 4: The majority of the moments surrounding 2010s and 2020s on the timescape were from the “SSO#10 – FRAME AND FREQUENCIES: SOUND SYSTEM FILMS WORLDWIDE” programme screened on February 15. SSO#10 Frames and Frequencies was a one-day film festival premiering sound system films from six continents: SST-produced films from Jamaica explore the island’s rich sound system heritage – and its future. Those from India, South Africa and UK show the outernational diaspora of reggae sound systems. Films from Brazil, Colombia, and Dominican Republic feature sound system scenes unique to those countries that have grown up independently from Jamaican influence.

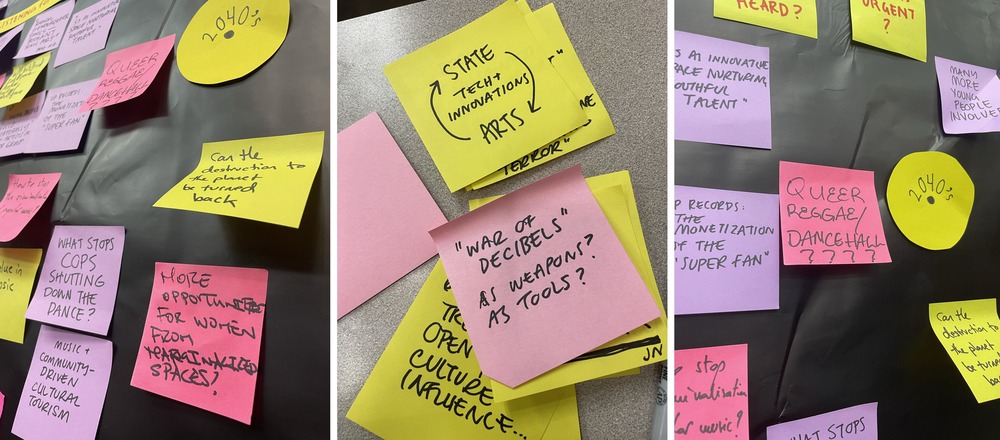

Figure 5: The ‘burning questions about our futures’ section (from 2020’s through to 2060’s) was mostly populated by audience members on the final day of the conference, with clear relationships to issues raised by conference presentations. Even though there are clear threads through the past decades to future questions, it is in this futures space that I am most interested. I quote Aboriginal scholar Arlie Alizzi here in order to echo his potent question: “What histories do we take into our futures?” (email correspondence with the author, 2016). This image combines three photos featuring some of the contributions around the 2040’s and 2060s.

Figure 6: This image shows the final result of the 4 meter-long physical sonic timescape at the end of the GRC across seven photographs. This is by no means a complete record of the insights presented, shared, and discussed at the conference, but indicates the depth and breadth of topics raised. I expect that our analysis will show strong translocal resonance regarding technological developments, policy and policing, as well as challenges to gender and queer representation over both time and space. With many of the non-geographically located questions relating to our futures opening doors to creative collaborations, further research opportunities, and even advocacy strategies – particularly regarding the celebration and protection of sound system culture worldwide.

Figure 7: I include here a screenshot of the digitised sonic timescape transcribed into Miro. Readers can access and edit the active page through this URL: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVKbxRizI=/

Next steps

The physical ‘sonic timescape’ served a unique purpose during the conference, inviting those attending the daily presentations and films to share their insights and reflections. The digital ‘sonic timescape’ serves a greater generative purpose to not only invite insights, but act as a growing repository of past, present, and future significant moments for the international community of researchers and practitioners to add to and draw from for their own purposes. I will play an ongoing role as a remote and asynchronous facilitator of this repository and hope that it acts as a collaborative and generative space for our shared research.

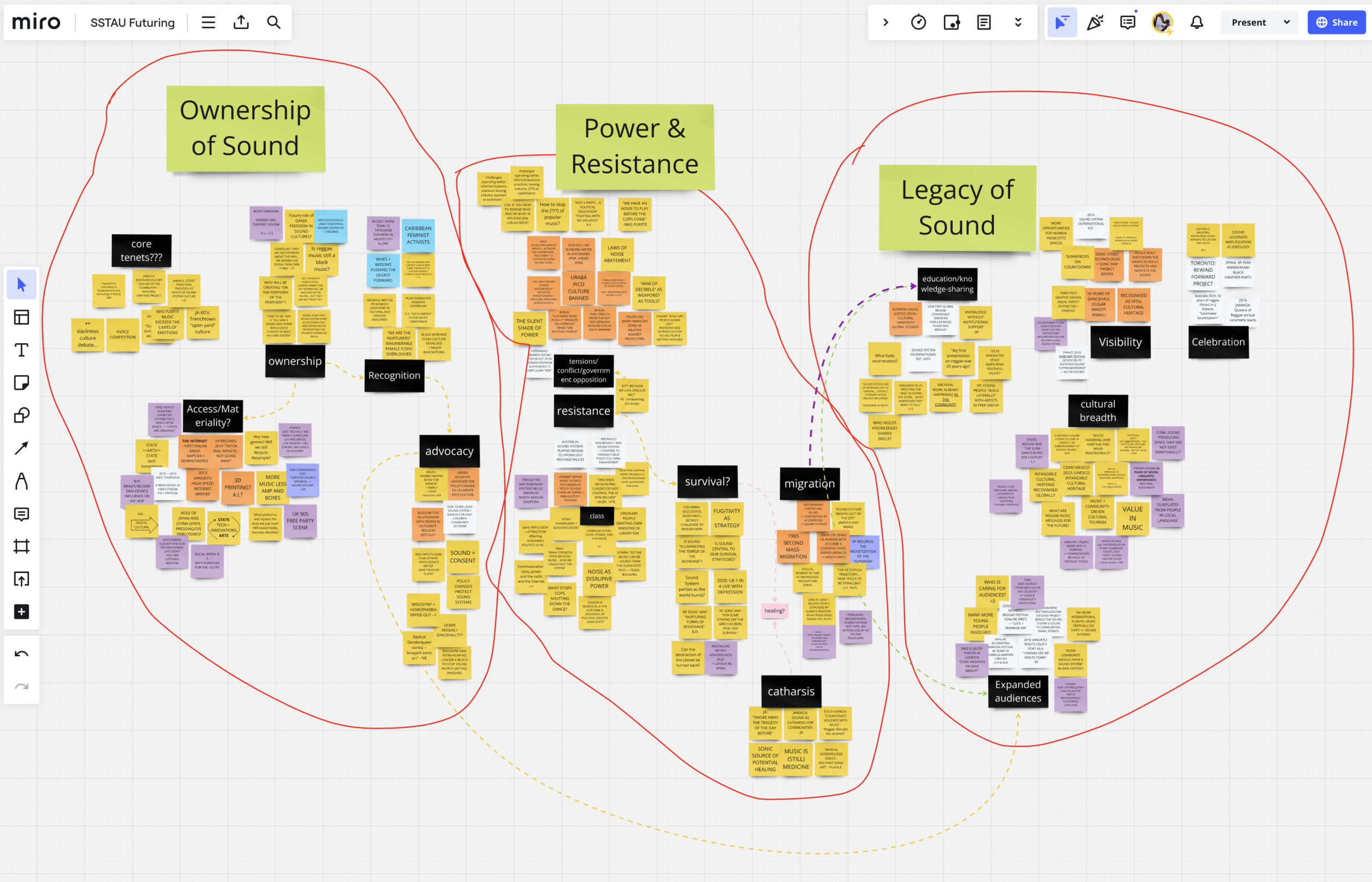

Post-conference, our research team has undertaken thematic analysis of the contributions to the physical board and sorted geographical and temporal connections between significant trends. Three major themes emerged so far: ’Ownership of Sound’, ‘Power & Resistance’, and ‘Legacy of Sound.’

Image 8: Screen shot of thematic analysis on SST Australia team Miro board.

Image 9: Screen shot of thematic analysis on SST Australia team Miro board.

Image 10: Screen shot of thematic analysis on SST Australia team Miro board.

‘Ownership of the Culture of Sound’ reaches beyond literal ownership of technologies, but also encompasses the core tenets and characteristics, issues of accessibility, materiality, recognition (with particular attention to the Caribbean feminists, “wives, and widows”, and a variety of policy advocacy taking place. There are also some generative futuring questions in this theme relating to sound and consent, “radical genderqueer sonics”, and the opportunities and challenges of AI, 3D printing, and rapidly changing music distribution platforms.

‘Power and Resistance’ details multifaceted and intertwined tensions, conflicts, and acts of resistance. Histories of conflict, opposition and obstacles faced by the proponents of Sound System cultures were told alongside stories of resistance and resilience. Stories that exist not just despite opposition, but sometimes in direct spite of opposition.

The ‘Legacy of Sound’ theme refers to the intangible, but nonetheless pervasive, historical-cultural impact of Sound Systems and their audiences. While much of this theme is positioned retrospectively, as it collates moments of Sound System celebration and visibility, it is also inherently future-focused as it grapples with how the Legacy of Sound will evolve and transform over time. This is particularly evident in conversations related to Audience and Knowledge-Sharing.

In the coming months we will be engaging in a backcasting process, starting with some of the possible, probable, and preposterous (Voros 2009) future projections in the 2060’s and working backwards from these to our current moment in time. We will share the observations of likely, desired, and undesired trajectories within the Miro board, and invite conversations over the course of the next 12 months, sharing our findings with all of those who have contributed to the sonic timescape.

The most immediate next step is to disseminate the digital sonic timescape to the global researchers engaged in the European Research Council-funded Sonic Street Technologies project, encouraging contributions on historical findings as well as collated future challenges and projections.

References

Anderson, Kevin. “Reconciling the electricity industry with sustainable development: Backcasting – A strategic alternative”. Futures. 33. (2001): 607-623.

Alizzi, Alizzi. Email correspondence with the author. 2016.

Augustyn, Heather. “Studio Sistren: Women at the Controls in Jamaica’s Early Era of Recording.” Kingston: 8th Global Reggae Conference Programme. University of West Indies (2024).

Bridger Robinson, John. “Energy backcasting A proposed method of policy analysis.” Energy Policy Volume 10, Issue 4. (1982): 337-344.

Boulding, Elise and Boulding, Kenneth. The Future: Images and Processes. London: Sage, 1995.

Cooper, Clare. “Design timescapes: Futuring through visual thinking.” Visual Communication, 0(0). 2022.

Cornish, Edward. Futuring: The exploration of the future. World Future Society, 2004.

Escobar, Arturo. Sustainability: Design for the pluriverse. Development, 54(2), 2011.

Fry, Anthony. Design futuring. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2009.

Hoyle, John R. Leadership and Futuring. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2006

Inayatullah, Sohail. “Six pillars”. Foresight, Vol. 10, no. 1. (2008): 4-21.

Schultz, Tristan. ‘Decolonising Techno-Colonising Indigenous Design Futures’, Strategic Design Research Journal, Vol. 11, no.3. (2018): pp

Jefferson, Michael. ‘Shell scenarios’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 79, no. 1, (2012): 187-197.

Lovins, Amory B. “Energy strategy: the road not taken.” Foreign Aff. 55 (1976): 65.

Stanley Niaah, S. Welcome message in 8th Global Reggae Conference Programme. Kingston University of West Indies, 2024.

Stowe, Maxine. A Comparative Overview of the Parallel Sound System careers of Kool Herc and Sugar Minott. Kingston:. 8th Global Reggae Conference Programme. University of West Indies, 2024.

Tomitsch, Martin, Borthwick, Madeleine, Ahmadpour, Naseem, Cooper, Clare, Frawley, Jessica, Hepburn, Leigh-Anne, Kocaballi, Baci, Loke, Lian, Núñez-Pacheco, Claudia, Straker, Karla, Wrigley, Cara. Design. Think. Make. Break. Repeat – Revised edition. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Bis Publishers, 2020.

Voros, Josef. “Big History and anticipation”, in R Poli (ed.) Handbook of anticipation. NYC, USA: Springer International, 2019

About the authors:

Dr Clare Cooper is a Lecturer in the School of Architecture, Design & Planning at the University of Sydney, Australia. Cooper’s research and pedagogy is informed by two decades of professional design practice, workshop facilitation, creative activism, and performing arts practice.