Exodus, Resistance, and the Stoppage of Time: Sonido Murillo, Monterrey

by Yasodari Sánchez Zavala

My uncle Raúl was older, he started with orchestral music, danzón, mambo, cha-cha… He first started with that music and then my dad added another rhythm, cumbia, and that’s when everyone started dancing, the rhythm started to change from tropical to Colombian, the two of them were old school sonideros, but my uncle Raúl started with the tropical and my dad brought in the cumbia, and that was the story, and we are still here, me and my brothers Henry and Lelo.

(Tino Murillo ‘El legendario’ and his original Murillo sonidero dynasty)

Research Preamble

La Independencia is the neighborhood of my paternal and maternal family. It is my barrio, the place where I grew up understanding that memory is resistance, a guiding force and a compass for the present. The love for this area, its music and its sonic identity dignifies our origin, our identity and our pride. At Indepe (as we affectionately name it) we are musical and sonic heritage, we make songs and dances that today have spread across the globe.

For more than eleven years I have been documenting the memory of the sonideros of the Independencia neighborhood and some of the southern areas in Monterrey, Nuevo León (Mexico). As part of my ongoing research project (Sintonía Sonidera / Somos la Indepe), I have interviewed approximately sixty key figures within the local sound system scene. This research has evolved into various forms of dissemination, aimed at recognising and safeguarding the heritage of the sonidero profession in northern Mexico. These include podcasts, fanzines, public space interventions, and documentary films.

Given the socioeconomic challenges faced by the sound system community during the COVID-19 pandemic, the project has also evolved into an incubator for sociocultural initiatives. We have organised dances, screen-printing workshops for older adults (focusing on sonidero-themed t-shirts), and photography classes for children, exploring themes of local community, nature, and techno-musical culture.

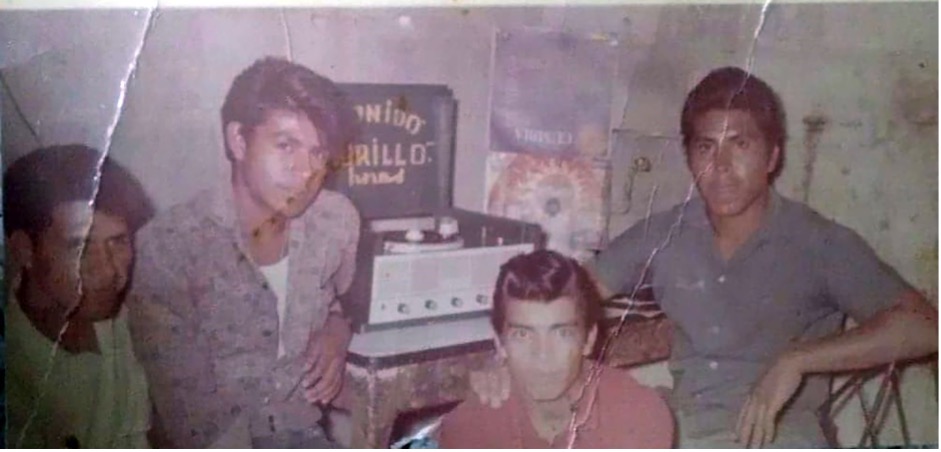

Image curtesy of the Murillo family

The Sound Memory of the Northwest

Many families in La Independencia originate from states such as Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, and Zacatecas—migrants who arrived in Monterrey with the promise of better days, higher wages, and a better quality of life, settling on the 260 hectares that stretch from the Santa Catarina River to the Loma Larga hill. This material and symbolic border helped to preserve some of the original practices of the settlers while also fostering the adoption of new ones, through an ambiguous and often harsh flow of nostalgia and joy, linked to the experience of the exodus.

The longing, challenges, and uncertainty led to pacts among the new settlers, who shared knowledge, techniques, and trades with one another while facing a city that discriminated against them based on their skin colour, educational level, and, above all, their socioeconomic status. Many trades and practices remained since the founding of Indepe, such as upholstery, tailoring, shoemaking, and the production of pipián and mole in a mill. However, none are as endemic as the profession of sonidero. Unlike many other neighbourhoods founded at the same time as Independencia, during those years of industry and migration, the sonidero practice became a symbol of identity for us. Leisure is a form of collective resistance in the neighbourhood; the exclusive taste for Colombian sound and music is a source of pride for the inhabitants. The founders of Indepe were visionaries of public space rights through the conquest of those hectares which they populated between paths, ravines, and streams. According to Pedro Valdés (Sonido Monarca), on their return from work, the inhabitants crossed stones, mud, and puddles, always greeted by melodies that signalled: “We’re getting home… what a beautiful song, surely there’s going to be a dance… we’ll have to turn up.”

The sonidero practice is the chronicle, will and resilience of an entire generation that conquered a territory and forged a neighborhood. The echo of the sound systems summoned and deafened the inhabitants, exuding through the streets the memory of their towns, their families, their loves, and times gone by. Without knowing it, Indepe adopted with its body and soul the melodies, lyrics, folklore and musical spirit of Colombia, and incorporated them as a fundamental tool for surviving in the face of poverty and exclusion.

The sonidero history of Indepe, uncertain by nature, dates back to the radio era: mambo, cha-cha, danzones, and orchestras were the sounds of the barrio and its shared patios; but also of the entire city and country. At that time, radio stations and music stores broadcasted the same musical genres nationwide. The first owners of sound equipment were not yet known as sonideros. Most of them lasted only a few months, perhaps a couple of years. These emerging practitioners presented music from their own homes, attracting neighbours, friends, and family after work. The pioneers of sound systems were not hired beyond their own neighbourhood, street, or home.

As noted by Gabriel Dueñez (Sonido Dueñez), one of the leading sonideros from this neighbourhood and the whole of Mexico, as well as one of the mythical originators of rebejada (slowed-down cumbia), the best-known names at that time were: Sonido Cepeda, by Pancho Cepeda; Sonido Brasilia, by Melchor and Julio Ontiveros; Sonido Banda; Sonido Murillo, by Raúl and Mario Murillo; and Sonido Venus, which – by the way – provided entertainment at the wedding of Don Gabriel and his wife Juanita in 1968.

Image curtesy of the Murillo family

Originally from Francisco del Rincón de León, Guanajuato, the Murillo family settled in the Morelia neighbourhood in the 1940s, and it is the street commerce that distinguishes them. Raúl Murillo was one of the first to walk the streets of Indepe, playing music for 50 or 70 cents while selling fruits and vegetables, his main occupation. Raulón, as he was affectionately called, drove his truck selling all kinds of fruits and vegetables, aided by a horn, announcing his presence with the music of the time. He is the figure who inaugurates the new profession in the Indepe neighbourhoods: the lord of the sound system, and he also founded Sonido Murillo alongside his brothers.

Raúl Murillo’s bold example became the model for many, showing them the possibility of owning a sound system and presenting these melodies to other neighbourhoods, as well as the opportunity to earn extra income, enliven evenings and weekends, and even accompany processions as a kind of cupid. Raulón passed the baton to his younger brother, Mario, who, by selling chewing gum at dances, managed to buy his own sound system and made his debut playing the same music genres. However, it was Mario who changed the way music was presented as an entertainer, marking another contribution to sound system culture in these neighbourhoods.

Mario’s charisma, voice, and witty phrases helped him establish Sonido Murillo y Hermanos. His neighbourhood – nestled between the streets of Morelia and Nueva Independencia – remains home to his most dedicated followers, many of whom continue to be loyal to this day. Mario Murillo’s children are also sonideros: Tino (Mario), Henry, and Lelo (who passed away in 2018), each with their own independent careers, and all highly respected and admired in the neighbourhood. Henry (Sonido Murillo El Internacional) is the one who has played the longest, both within the country and abroad. This is worth highlighting, as most sonideros stopped performing in the early 2000s, due to the wave of drug-related violence the country experienced, as well as the global digitalisation of music and the economic crisis.

“Dear friends, ladies and gentleman’s, do not forget that the invitation is for you to come this afternoon, tonight, to dance, to enjoy, to have fun at this great Colombian dance party. Remember that you will be entertained as always and once again by your very tropical number one: Murillo y Hermanos. Yes, why not? We are sending the following recording especially for all the beautiful people, who are with us tonight… Those who know good Colombian music. Go ahead, go ahead and go again!” Play the good ones Raulón!

(Mario Murillo Jr. remembering his father’s greetings).

Trade, and above all, the quest for tropical music records, led Raulón to Mexico City in 1970. Alongside Toronja, a colleague from the sound system community, Raúl is recognised as one of the leading figures in tracking down and collecting unreleased or original music – that is, music not played on the radio or widely known. In this pursuit, both men shared a partnership with José Ortega Morelos of Discos Morelos, a promoter of record labels in Mexico City. José became an accomplice in preserving the sonidero memory of Indepe and the musical groups that emerged in Monterrey and the surrounding metropolitan area during the 1980s, including Celso Piña.

In those years, recalls Tino Murillo, sonideros played tracks by Tropical Vallarta, Tropical Palmeras, Sangre Joven Tropical, Renacimiento 74, and Súper Estrella – and it was these that first triumphed in Indepe. Mario, his father, also a music enthusiast and adventurer, went on a trip to Mexico City on his own in 1973. Unfamiliar with the metropolis and with little experience in the sound system scene, he embarked on a journey through Tepito, Peñón de los Baños, and the centre of Mexico City, meeting famous sonideros such as Sonido Sonoramico, Sonido Arcoíris, and Sonido Fascinación.

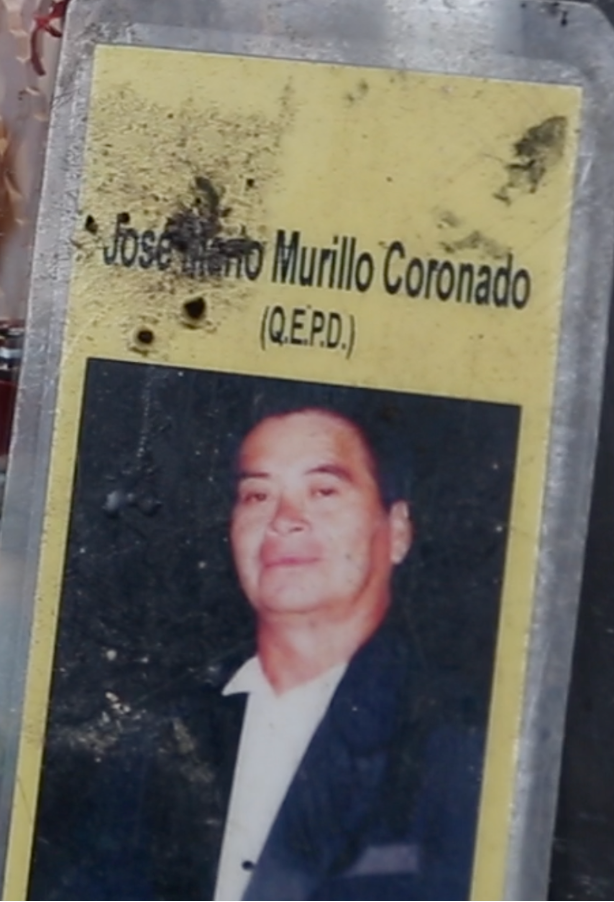

Mario Murillo’s holy card from the Murillo family archive

It was on this trip that Mario Murillo first brought Colombian music to Indepe. At that time, the hits were from Mike Laure, Carmen Rivero, and Linda Vera. Most of these melodies blended tropical genres with orchestras (including cumbia) and incorporated new instruments such as electric guitar, güiro, trumpets, trombones, and brass, among others. However, it was the songs of Los Corraleros del Majagual that defined the taste for what is now known in Monterrey as Colombian music. This was the first musical group that Indepe embraced.

Mario continued travelling to Mexico City with his son Tino to source music. Among the most sought-after Colombian cumbia artists at the time were Lisandro Meza, Andrés Landero, Adolfo Pacheco, Liborio Reyes, Alfredo Gutiérrez and his sons, César Castro, Aniceto Molina, Nacho Paredes, Gilberto Torres, Armando Hernández, Calixto Ochoa, Chico Cervantes, Eliseo Herrera, and Julio Erazo. During these trips, Mario learned about pitch alteration—that is, changing the turntable’s speed while playing tunes, a technique sonideros developed out of technical ingenuity, for enjoyment and to enhance the rhythms. It was also on these trips that he discovered sonideros’ obsession with acquiring better speakers, equipment, and technology in order to stand out and be unique in their craft.

After those trips, Mario and Raúl Murillo modified their sound system. In an intuitive and playful way, they altered it, changing the controls and bulbs, making it sound louder and with a different pitch. Just as he was in the middle of a country tropicalized by the sound systems, he decided to do his own thing. Mario – with the influence of his brother Raúl – covered his sound system with colourful plastic, printed with stars and palm trees. His son Tino helped him to rewire the speakers, make baffles and everything that could technically improve the sound. Mario became an influence for many sonideros from Monterrey, who regularly came to him to learn, both technically and aesthetically, ways to modify and beautify their RADSON sound devices, as well as to buy and exchange records.

The sonic uniqueness of the northwest

Unlike other sonidero cradles, where extensive possession of equipment, technology, and transportation is a source of pride and recognition, Indepe’s practitioners did not follow this path. First, because the sonidero job did not provide a stable enough income to support a family; later, because acquiring new music was always their priority, mainly from shops in the centre of Monterrey, such as the Gabino Hernández’s Discoteca Popular (the most prominent record shop in the memory of Indepe’s sonideros). In some cases, these records were sourced from nearby cities like Reynosa, or even from North American cities such as Houston or Miami. Finally, because dances in Indepe were typically held in houses, streets, and small venues, with limited space due to the neighbourhood’s topographical irregularity. For this reasons, the conditions were not ideal for holding massive events or acquiring audio equipment with greater power.

It is important to mention that in Monterrey there were other municipalities and neighbourhoods where sonideros had a strong presence and which also influenced the regional spread of Colombian music. However, the job of being a sonidero and music collector has remained firmly rooted in Indepe, where the everyday soundscape is transformed through loudspeakers, cumbia, porros, and vallenato every time there is a celebration.

Final note

There is still much to be done and revealed regarding the memory and cultural heritage of sonidero music in the northwest of Mexico. From the música rebajada and Gabriel Dueñez’s sonido, to the generational and female shift represented by Gaby and Nunis Dueñez; from live radio programmes like La Terraza, led by veteran sonidero Rodrigo Arellano (Sonido Paraíso), to the continuous trips to Colombia by Jorge Rada (Sonido Rada) to acquire music and visit “the second homeland”; from the remarkable work by Odilón Arellano (Sonido Paraíso Caribe), who customized sound system equipment, to the restoration of album covers by Rafael Valero (Sonido Luna Azul) using collage techniques.

This is a brief story of the Murillo family (Raúl and Mario), who lead with their sound systems the impetuous love for music and the Indepe neighborhoods. They triumph in the unique definition of being sonidero from the lack of much, but the will of everything in the northeast of the country. They are pioneers in the dissemination of Colombian cumbia, but they are also mediators and leaders when it came to making improvements in neighborhoods, delivering deeds to settlers, promoting the economy of a merchant, or resisting in community against the lack of health services, education and job opportunities. The story of Raúl and Mario Murillo is unknown, like many other sonideros from Indepe or the southern area, who managed to create leisure spaces, turning the streets into a community through music and sound equipment.

This is a brief history that is, at times, overlooked or discriminated against, but at other times, appreciated with optimism and without disillusionment. Many have entered this territory with opportunism and a desire for profit, constructing superficial fictions about sonidero culture, perhaps driven by the entertainment industry and global digital platforms. This research (Sintonía Sonidera) seeks to dignify the memory of the sonidero profession, as well as that of composers, musicians, families, and friends. It is a brief history of the Indepe neighbourhoods, of the lords of sound systems, a courageous story that holds the love of our origins, of the sonority of a community that, with its lyrics, rhythms, and folklore, continues to pulse from hill to river: we are Indepe, we are Colombia Chiquita (Little Colombia), we are Sintonía Sonidera.

—

About the author:

Yasodari Sánchez Zavala is a Mexican artist, academic, and documentalist. Winner of scholarships and distinctions for her work related to migrant, indigenous, working-class communities, musicians, and sonideros in the Monterrey metropolitan area.