El Picó. In Search of One’s Own Sound

A unique Colombian SST, the picó consists in one or more large speaker boxes, hosting one or more drivers, beautifully hand-painted with colourful artworks representing the name of each unique set, mainly blasting African music such as soukous, highlife and makossa, among other genres. SST welcomes new bloggers José Camilo Ríos Alarcón and Adriana Alexandra Ayala Bejarano, who take us through a journey across time to explore the musical, technological and cultural substratum responsible for the birth of the picó in the city of Barranquilla, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

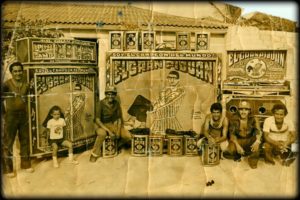

Picó El Gran Pijuan, Barranquilla. Image from blog Africolombia

Introduction

The history of the sound system of Colombia spans more than seven decades. Memories of the picó in the Caribbean region of Colombia refer not only to music but tell the story of an era: the appropriation of the latest technology, the production of identity and of the social fabric, life in the barrio and popular street festivals. A community gathers around the picó and expresses itself as it comes together in its own ways of being, perceiving and designing everyday life. That is why it is important to dialogue with and look more closely at this particular way of inhabiting the everyday, as it offers a specific angle to explore the unique know-how of the sonic street technologies.

Where does the journey towards one’s own sound begin?

As a native of Bogotá, I now understand that I was born in a cosmopolitan city. This means that a part of me is made up of an assortment of influences that in Bogotá we have all become used to listen to, a jumble of music from different latitudes: electronic, salsa, vallenato, rock in Spanish, hip hop, classical, metal, reggae, which makes them feel somehow close and familiar.

However, as I once heard in the voice of Maestra Lucy Herney Cachimbo, ‘How much of what we consider ours is really ours?’ [1]

This research journey begun many years ago, originating in my interest in the music that can be heard on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, in those sounds vibrating from the picós, which Maestro Nicolás Contreras Hernández describes as ‘the electronic drums of our own territory’ [2]. This first brief account of the sound system scene of Colombia is focused around the city of Barranquilla, although it does not stop there, because I acknowledge that the picó is vast culture, can be found throughout the entire Caribbean Region of Colombia and extends towards the Pacific shores across the Urabá.

In the ‘golden port’ of Barranquilla during the 1930s, a drop in price made victrolas or gramophones accessible to different social classes. As a result, this technology started to be appropriated by a first generation of fledgling picós, as noted by researcher Jorge Giraldo [3]. At the time, Barranquilla was experiencing both a demographic growth and an unparalleled economic boom, mainly thanks to the development of international trade, to the point that Puerto Colombia and then ‘La Quilla’, as Baranquilla is known, became the most cosmopolitan areas in the country in just a few decades. Historian Jorge Villalón Donoso has made an exhaustive account of this historical period of Barranquilla. [4].

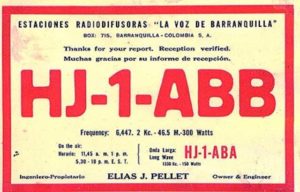

At this stage, the development of a music scene in Barranquilla came with the impetus of modernity and through radio. At the end of 1929 La Voz of Barranquilla, Colombia’s first radio station, was founded by engineer Elías Pellet Buitrago. The hertz waves kept coming with Emisora Atlántico in 1934.

Radio Station La Voz de Barranquilla. Image from Tweeter @socialhizo

Along with the radio stations came the rise of studio orchestras that performed music live over the air, livening up shows and backing guest artists. This is the time when the great music orchestra tradition of Barranquilla was born. These big band type orchestras, inspired by the jazz bands such as Benny Goodman’s and Glen Miller’s, made a deep impression and became a benchmark in the cultural life of Barranquilla. Another critical influence was that of the powerful Cuban radio stations, mainly CMQ, Radio Progreso and La Cadena Azul, all broadcasting from La Havana, that could be listened to on the Northern Coast [5].

La Orquesta de La Voz de Barranquilla, directed by Emirto de Lima, was quickly joined by La Orquesta Sosa, founded by Maestro Luís Felipe Sosa in 1932. A jazz band-type orchestra, the Orquesta Sosa included in its repertoire not only polkas and waltzes, but a marvellous collection of songs with a local flavour, and musical scores began to incorporate elements of local music [6]. Some of the several influential directors, composers and arrangers from Barranquilla in those days were Pedro Biava; Gido Perla, director of the Atlántico jazz band; Pacho Galán; Antonio Peñaloza, among many others.

Orquesta Emisora Atlántico Jazz Band. Image from Tweeter @Jamon_Salve

These orchestras performed in the main social clubs and dance halls of the time. Those were the glorious days of Paseo Bolívar, after the city’s electricity supplier became the property of the Electric Bond & Sherer Company of the United States in 1928. Barranquilla continued on the route to progress with the construction of modern hotels, the most known example being El Prado, inaugurated in 1930; together with the stunning life of the social clubs of the city’s commercial and industrial elites, such as El Club Barranquilla, El Club ABC (for Art, Beauty and Culture), El Club Alemán, where the crowd enjoyed dancing mazurkas, polkas, waltzes, pasillos and bambucos; the splendor of the great ballrooms with their unforgettable costume parties, such as El Salón Carioca and El Jardín Águila, inaugurated in 1936 with the now legendary visit of La Orquesta Casino de la Playa and La Orquesta de la Habana; and the monumental theatres, cinemas, and stores, with Sears among the most important, founded in the early 1950s [7].

The directors of the Caribbean dance orchestras had to adapt popular music to the ears of the Barranquilla creole elite, in many ways whitening it and dressing it in tails. This topic has been documented by researchers Peter Wade and Manuel Antonio Rodríguez [8]. Similarly, the hottest popular music made it to “la Quilla” with artists such as Guillermo Buitrago, Bovea, Alejandro Duran, Abel Antonio Villa, Luis Henrique Martínez y Aníbal Velásquez, with newly established record labels kickstarting successful careers for many of them. In 1945, engineer Emilio Fortou Pereira founded one of the most important record companies in Colombia, Industrias Fonográficas de Barranquilla and his label Discos Tropical established its facilities in Barranquilla’s industrial district. Shortly after, in 1948, Emilio Fortou began to manufacture records, with the arrival of the country’s first pressing plant [9].

Aníbal Velásquez, LP cover, 1965

In the 1950s the picó began to take root. Once the commercial heyday of Barranquilla passed, the city moved towards another historical period in which culture had a relevant and significant role. It was in the 1950s that El Grupo de Barranquilla published the now-revered magazine Crónica, and “la Quilla” witnessed the rise of one of the most important writers of the 20th century, Gabriel García Marquez who, together with Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, Alfonso Fuenmayor, Alejandro Obregón and others, surely had memorable long nights in El Viejo Chop Suey, such as the unforgettable appearance of Cuban orchestra La Sonora Matancera in 1953. It is precisely Cuban music – guaracha, guaguancó, mambo, danzones, guajira, chachachá, pachanga – along with New York salsa, jibara music from Puerto Rico, vallenato and porro, were the genres the picós played most at that time (Giraldo, 2016).

Salsa Picotera Vol 1 LP, cover, 1978

When the turntable was adapted to the picó in the 1950s, the desire to enjoy this musical form became established in cantinas. Gradually, jukeboxes were replaced by picós, whose carefully selected music programming became more and more popular and appreciated. According to researcher Jorge Giraldo (2016), because of the good reception of the picó in cantinas, many owners decided to take them out to the street to provide musical accompaniment to the verbenas. A verbena is a space that is suitable for street festivals and celebrations that take place mainly open air, which are then conceived as community events. The social scene of the verbena would eventually constitute the platform from which the picó was catapulted into the open air, taking it once and for all from indoor venues into the streets.

As Sidney Reyes and Osman Torregroza have argued, the verbena had a substantial importance in the social fabric of the barrios. The verbena originated from the community social clubs of the neighborhood, where the carnival celebrations and the festive life in general were organised.

“These clubs would organise in advance the orchestras for the main barrio festival, the dancing acts and other participants in carnival parade ensembles, and publicity around and selection of the carnival queen for the barrio, among other activities. The verbena was then the epicentre of the social organization of the carnival balls and was part of the festive life of the whole range of barriadas, or slums, ” (Giraldo, 2016: 55-56)

Verbenas in Barranquilla 1970. Image from Blog Africolombia

It was in the festive neighbourhood life of Barranquilla and the social substratum of the verbena that the picó was able to establish strategic alliance to spread popular music. In 1960, when the picó went mainstream, there were 52 renowned verbenas in Barranquilla that brought together people from different social classes to enjoy the music selection.

Still enveloped in the long shadow of modernity and progress, this first account of the picó in Barranquilla leads me towards an assessment from the perspective of joy, music and festive life, the encounter and communication with the ‘other’. In the reflections hidden behind the masks, in the costumes, thinking while laughing, the comical side of life is perceived; you hide yourself in order to appear, and you appear in order to live. While the dancing body responds to and deciphers its own sound, who was I? What was I? And where did I come from? As it happens in the Carnival, everything begins with putting on a good costume.

Author: José Camilo Ríos Alarcón.

Editing and correction: Adriana Alexandra Ayala Bejarano

Extra translation support: Liv Sovik

—

Adriana Alexandra Ayala Bejarano holds a degree in Humanities and Spanish Language from the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas of Bogotá. Her work is focused on the production of community-based content for communication contexts, mainly on the radio and in the promotion of reading and writing. She currently participates in Palenque Sonoro and Brigadas Comunitarias, lectores de paz-es.

José Camilo Ríos Alarcón holds a degree in Ethnology from the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. He is a radio director, focused on contextualizing the expressions of the picó, the sound system and the sonidero. A lover of dub, cumbia and champeta, he addresses the issues from their historical, sociocultural and aesthetic substratum. He participates in Palenque Sonoro.

—

References

[1] Góngora Bonilla, Nidia y Ciudad, Adriana. Disco doble: Ángeles del cielo oigan mi voz, Cantos de Alabaos, Timbiquí, Cauca. Llorona Records, CD, 2018.

[2] Contreras Hernández, Nicolás. Conversatorio: La Negramenta Se Entiende. Facebook profile: Champeta Patrimonio Inmaterial (@champetapatrimonio); see also Contreras Hernández, Nicolás. La cultura picotera: continuidad de la herencia africana en el alma de las fiestas populares del Gran Caribe, Barranquilla: Huellas (Universidad del Norte) No. 80-81-82, 2008: 126

[3] Giraldo, Jorge. Música champeta y africana en el Caribe colombiano, Argentina: Babel Editorial, 2016

[4] Villalón Donoso, Jorge. Luis Nieto Arteta, YouTube channel, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCITt2SVWOGvBJYzwehwPQ1w ; Villalón, Jorge. Barranquilla en el tiempo de la prosperidad de milagro 1947-1957, Barranquilla: Huellas (Universidad del Norte) No. 40, 1994: 14

[5] Gonzáles Henríquez, Adolfo. Calidad en la vida musical en la radio barranquillera, Havana: Boletín de Música No. 117 Casa de las Américas, 1989: 21

[6] Rodríguez, Manuel Antonio. Musicalafrolatino, YouTube channel, https://www.youtube.com/user/musicalafrolatino/about

[7] Solano Alonso, Jairo y Bassi Labarrera, Rafael. Carnaval de Barranquilla: patrimonio musical y danzario del Caribe Colombiano, Barranquilla: Ediciones Universidad Simón Bolívar, 2017: 111.

[8] Wade, Peter. Música, raza y nación. Música tropical en Colombia, Bogotá: Vicepresidencia de la República Departamento Nacional de Planeación Programa Plan Caribe, 2002.

[9] Guacaneme Gómez, Andrea Carolina. Discos Tropical en el Fondo Sonoro Antonio Cuéllar. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, 2017