Copyrights and copywrongs in Jamaican music

In this blog post, friend of the SST project, Dr. Enrico Bonadio of City, University of London reviews the just published Rude Citizenship: Jamaican Popular Music, Copyright, and the Reverberations of Colonial Power by Larisa Kingston Mann. Here at the SST project, we have been attending to the many ways that different kinds of technology – such as the legal apparatuses – intervene in the development of SST. With Rude Citizen, Dr. Bonadio takes us into the techno-legal world of copyright that created the framework within which Jamaican sound systems and music developed. This legacy informs the status in legal, creative and social status of the industry today.

Mann, Larisa Kingston. 2022. Rude Citizenship: Jamaican Popular Music, Copyright, and the Reverberations of Colonial Power. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

by Enrico Bonadio – The City Law School (City, University of London)

Larisa Mann’s book is a welcome addition to the (short) list of academic works focusing on how the lack of copyright enforcement has contributed to the development of various Jamaican music genres, i.e. Jamaican boogie, ska, rocksteady, reggae and dancehall.

While this topic has already been addressed in the past by some commentators (Jason Toynbee is one of them), Larisa’s analysis brings the focus to another level, also expanding on the Jamaican music scene of the new millennium. The ethnographic research she conducted in Kingston has allowed her to get an invaluable insider view.

The book’s common thread is that cumulative creativity has significantly contributed to the development of Jamaican music throughout the decades – and that copyright has not played a major role in such development. Larisa makes the point that the constant reuse and adaptation of music and recordings created outside the island, with the insertion of local vibes, idioms, rhythms and styles, have been the structural elements of the various Jamaican genres throughout the decades (p. 45).

This is very true. Borrowing practices have always pervaded songwriting and studio production in Jamaica, starting from the 50s through the 60s, 70s and beyond. And the role of sound systems’ operators like Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd and Duke Reid in accommodating such practices has been crucial, as highlighted in Larisa’s book. Obviously, music borrowing has not been practiced only in Jamaica – many other music genres all over the world have advanced through cumulative creativity, as Larisa again notes (p. 14). But what has been achieved in Jamaica, a relatively tiny island with a small population, in terms of quality and quantity of music production, cannot probably be matched by any other country. Such success has also been due to the ability of songwriters and recording artists to borrow from and readapt previous riddims. As Larisa points out:

- “Reusing familiar sound or collection of sounds facilitates an interactive and social musical experience, drawing together musical practitioners – instrumentalists, voices, and dancing feet – into a coordinated but flexible moment of interaction. This reuse also contributed to a common culture of shared knowledge and experience. […] In Jamaican music, these practices made use of verbal quotations, musical quotations, and prerecorded selections” (p. 59);

- “Running the riddim was not seen as lack of creativity but a way of threading a musical narrative together – still exercising track selection through the order of which version to play next and engaging with the shared memory of riddims reaching across time and within a community of knowledge. […] Riddim traditions emphasize the way Jamaican popular music relies on shared knowledge as a foundation of creativity” (p. 155).

The creative process behind dub music is a case point. As is known, this is a genre of electronic music that grew out of reggae in the early 70s (mainly due to pioneer figures such as King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry) and which features plenty of reverbs and studio effects. As Larisa points out:

- “dub is not the act of a sole creator. Dub music highlights the existing ruptures in such formal legal relationships and the cultural logic that underlies them, in practice and sonic form as well. By removing some sounds and tweaking or altering others, dub opens up a conversation about the origins of sonic meaning and the means by which it reaches our ears” (p. 63).

That creative processes within the Jamaican music scene have a cumulative nature is reflected in recording practices, especially in the early years of music production in the 60s. Indeed, it was common practice for recording artists signed to a specific producer (e.g. Coxsone) to record tunes for the competitor (e.g. Duke Reid). Members of The Skatalites band amongst many others exactly did so. As Larisa reminds us, “virtually the same instrumentalists played [the same] tunes in rival [studios]”. I happen myself to have in my collection recordings produced by members of The Skatalites (whom were all signed to Coxsone) for competing labels including Treasure Isle productions supervised by Duke Reid.

Sir Coxsone Dodd’s Downbeat sound system, Jamaica Jamaica!, National Gallery of Jamaica, 2020

Switching from studio to studio with flexibility was widely accepted, causing a sort of contamination between competing producers. As Lloyd Bradley notes in his 2002 book Reggae: the Story of Jamaican Music, “… there wasn’t much that could be kept secret or exclusive. Ideas leaked all over the place and everybody played on practically every producer’s sessions” (p. 11).

The practice of re-use previous riddims and works in Jamaican music continued after the golden age of the 60s and 70s, into the post-Marley digital era. Larisa points this out:

- “riddims continued to recirculate with ever-evolving vocals. […] When a recording was reused, not only could vocals and instrumentals be separated, but also shorter snippets or separate tracks could be separated and reused. In the same way that DJs would select a particular song (or part of a song) to elicit a desired crowd response, a producer could now select a musical excerpt (a bass line, a lyrical interjection, a three-second drum roll)” (p. 59);

- “… the Jamaican tradition of using prerecorded music as a main source of raw material for creative performance has continued. […] riddims themselves have remained the basis for musical involvement. When in recording studios, not only did I see producers pulling from stacks or lists of riddims as they decided how to work with an artist, but on occasion an artist would stride into the studio and demand that the producer “give me the riddim” of a hot tune or a historic tune” (p. 76)

Not only copyright has failed to play a major role in the development of Jamaican music. Actually, the lack of copyright enforcement has been crucial. Without being inhibited or scared by potential copyright-based complaints, Jamaican songwriters and performers could appropriate and adapt others’ riddims and (pieces of) recordings – thus giving local music an evolutionary impulse. Again, Larisa is fully aware of this and notes that “the use of recordings as raw material rather than finished product and the musical practitioners’ ongoing interest in interacting with those recordings have continually set Jamaican popular music against copyright law” (p. 7).

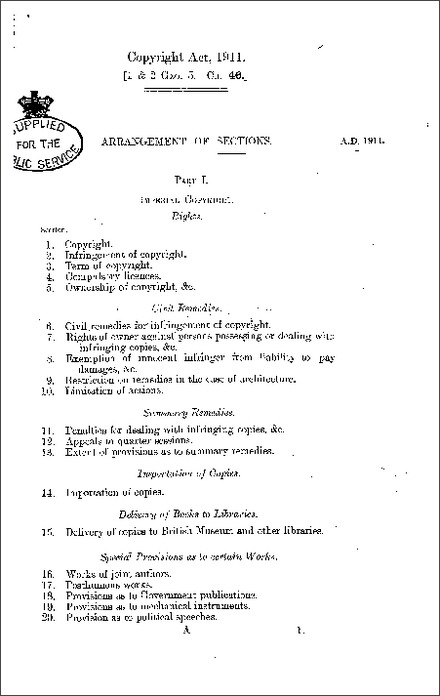

The Copyright Act of 1911

In theory, the UK Copyright Act of 1911 formally applied to Jamaica, but there was basically no enforcement and little rights management. After independence from Britain in 1962, the 1911 act and a local statute of 1913 that had implemented it, were transposed into Jamaican national law (N. Daley – N. Foga, Jamaica Beyond The TRIPS Agreement (2007) Managing IP). But again no much enforcement of copyright materialised. Jamaica would not sign and ratify the Berne Convention on copyright until 1993. As noted by Lloyd Stanbury in his 2015 book Reggae Roadblocks: A Music Business Development Perspective, prior to the enactment of the Jamaican Copyright Act in 1993, there was the widely held belief that copyright law did not exist in Jamaica (p. 161).

Also, in the 60s and 70s the British collecting society PRS (Performing Rights Society) did not pay much attention to the Jamaican market, and therefore did not police unauthorised copyright exploitation in what was considered a small Caribbean island. Larisa also reminds us that PRS was “apparently uninterested or unable to assist Jamaican instrumentalists and vocalists in copyright matters” (p. 57), and did not increase its representation nor appeared particularly motivated to ensure that royalties reached Jamaican performers (p. 65).

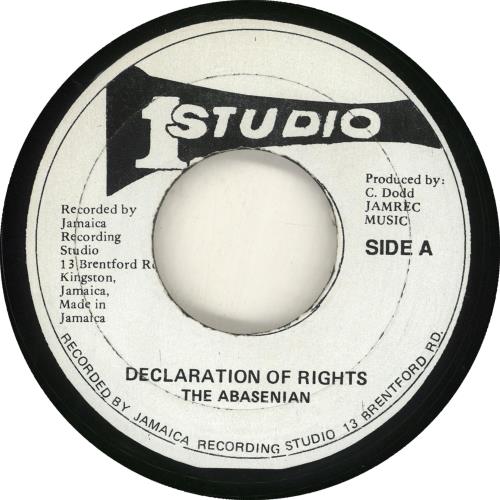

Studio 1 Recording and Publishing

This is not to say that no Jamaican songwriter or recording artist was interested in copyright and the revenues it could generate. Those who reached international notoriety (especially since the 70s) often joined collecting societies like PRS as well as the US societies ASCAP and BMI. And they did so – Larisa notes in her book – to capitalise on the better infrastructure for monitoring the sale or use of their compositions or recordings outside Jamaica (p. 68)

But the majority of Jamaican artists, especially in the 60s and 70s, did not care much about legal technicalities. They basically ignored that copyright could give them some form of tangible advantage such as mechanical royalties. They did create music and recordings out of their passion for music. In other words, intrinsic motivations and not the availability of copyright, pushed them to come up with musical works. Of course, musicians wanted to be paid by producers. Yet, as Larisa comments in her book, producers did pay (low) amounts to recording artists, but “as a matter of justice rather than law” (p. 57).

Interestingly, Larisa further notes that intrinsic motivations and low payments still characterize the Jamaican music scene of the present times. She points out that “[m]ost artists I spoke with did not describe royalties as a significant source of money for them” (p. 115), and that “the forces that motivate cultural expression and give it meaning originate outside copyright law” (p. 185). This is echoed by the inability of current copyright regimes to accommodate musical creative processes which are based on the appropriation and adaptation of earlier songs and melodies. As Larisa pointed out, drawing on her ethnographic research:

- “I never observed a discussion of royalties or licensing in relation to this practice. Recording studios still draw on hundreds of shared riddims and sample, including riddims derived from foreign songs” (p. 76). “Home studios have proliferated, continuing and extending traditions of musical reuse as new technology enables cheap duplication, sampling and editing” (p. 77). “These changing technologies of musical reproduction again highlighted the gap between local practices and the presumed interests and values of copyright” (pp. 77-78).

- “The DJ’s musical creativity demonstrates values that do not fit with the strictly commodified and bounded understanding of musical recordings as finished works. […] “this extension of Jamaican performance traditions, and the new ways that Jamaican built economies of reputation and performance on them, fit poorly with copyright law’s continuing focus on fixed, individualistic control of recorded works” (pp. 79-80).

Obviously, this has not prevented the Jamaican government from launching campaigns in the latest three decades aimed at promoting a copyright culture in the local creative industries. These campaigns have intensified after the introduction of the Jamaican Copyright Act in 1993, as noted by Larisa (p. 73). The government could not do otherwise as Jamaica has been since the very beginning (1995) a member of the World Trade Organization, which requires states to protect strongly intellectual property including copyright.

Studio 1 Record Label

The protection of intellectual property has therefore become a feature of the Jamaican legal system, with disputes being fought between songwriters, performers and estates: the bitter litigations involving the Bob Marley estate (managed by his wife, Rita Marley, and children) and the Coxsone and Treasure Isle’s catalogues are just some examples. Larisa herself in her book mentions that Jamaican dancehall performer Vybz Kartel – as a consequence of a dispute – had to destroy all copies of his version of a US song produced by the EMI-owned label Ne-Yo (EMI) (p. 82).

But the fact that copyright has lately entered the Jamaican music scene does not change the reality of what has made possible the development of so high-quality and successful Jamaican music genres throughout the 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond. Cumulative creativity has been, and to some extent still is, a characterising feature of Jamaican music. Larisa’s own statement in her book, i.e. that in Jamaican music there are “more authors than owners” (p. 65), perfectly epitomizes this feature.

I cannot help but recommend reading Larisa’s book. It is interesting, thought-provoking and stimulating. It will also guide you through a journey to discover the beauties and secrets of Jamaican music, from the mento of the 50s to the modern era.