Colombian Picó Graphics Vol. 2

One distinctive feature of Colombian picó culture is its strong visual identity. A previous blog provided insights into poster-making techniques and the various trends associated with the Caribbean cities that serve as strongholds of this culture. In this week’s blog, researcher Manuel Nieves delves into the art of painting sound systems, explaining the cultural significance and function these unique artworks hold for both owners and fans, as well as the main aesthetic trends.

by Manuel Nieves

The picó scene in Cartagena and Barranquilla pushed the owners to create a visual identity and personality for each picó, as stated in the previous blog. The handmade painting or pintura on the canvas is the most important feature of a sound system when it comes to recognition. Having a strong visual identity allows picós to interact with their crowd and between them; on the verbena (picó party), the personification of technologic and human networks conveying a picó’s power and prestige is embodied in animals, heroes, gods, monsters and so on.

This leads us to explore our key concept, related to poster lettering, picó painting and basically the whole picó culture: aleteo. Also expressed as azaro or vacile efectivo (Nieves, 2020, p. 17), aleteo refers to a cultural practice of boasting in which an individual always refers to himself as the best, the most guapo (boldest), the most skilled, the one and only. The recognition that although everyone is different, nobody does it like me. The picó scene is fueled by competition, power display and boasting: the search for exclusive records, for improved technology, for the best show performance. The recorded speeches that we can hear in the placas [1] are just more evidence. In the following section we are going to present the picó painting through its techniques, trends and narratives, to better understand aleteo as the driving conceptual force in picó’s aesthetics.

The visual aleteo of picó painting

The consolidation of a graphic language for the picó scene has been a network construction: disc jockeys, sound engineers, music lovers, carpenters, media, politics, etc. have all played a role. So before trying to arrange any account of picó painting techniques, I would like to acknowledge some of the painters who made and continue to make visual aleteo: Alberto Cuesta Rodríguez (Alcúr), Alexander Lugo (Alsander), Armando Cuesta Vargas (Arvacu), Belisario De la Matta (Belimastth), Byron Herrera (Byron), Edgardo Sarmiento (Edgar), Edilberto de la Hoz (Eddy), Édison Morales (Edimor), Gerson Acosta (Gerson), the brothers Magú and Enrique, Martin Olascoaga (Martin), Máximo Forero (Max Forero) Raúl De la Rosa (Raúl), Rodolfo Comas (Roco), Samuel Pacheco (Zurdo), William Gutiérrez (William), Wilmer Gastelbondo (Wilmer), Wilmer León Mora (El Negro).

Bearing in mind these painters, we should ask ourselves about the canvas they use. How do they adapt their aesthetics to the materiality of a sound system? Which surfaces do they paint when they are involved with a specific picó? Most of the traditional format picós, also known as turbos, use to have a central console (dj booth), one or more main boxes for bass speakers, a few long horizontal boxes for mids and trebles, and a number of smaller boxes to be hanged up on walls or trees. Depending on the investment of the owner, the set up can also include extra amplifier racks, a rack for vinyl records, a console for effects or even light controllers.

The speakers of the traditional picós are usually covered in a rough cotton fabric called cañamazo. This fabric is highly durable and is used to protect speakers from heat, dust, and humidity, as well as to display paintings. In terms of proportions, canvases can be found in vertical, horizontal, and square formats, with the latter being the most iconic for picós. However, the painter’s work is not limited to the canvas alone. They also paint the margins that frame the speakers. In other words, there are at least three painting areas for each picó box: the front speaker fabric, which will feature the most iconic painting or lettering; the front margins, where slogans and graphic elements may be added; and the sides and back of the speaker boxes, usually painted in a single colour or with simple textures.

Image 1. Close up of “El Coreano” picó painting by Zona Cero.

Moving from the frame to the canvas, we should ask ourselves about the techniques employed by the painters. As seen in image 1, the fabrics used to cover picó speaker boxes are a low-resolution medium as the ability to depict details (i.e. perceivable difference between elements) is low in comparison to size. This is due to the tiny holes that are a feature of this type of fabric, which are in turn crucial to allow sound waves to spread. The low-resolution requires painters to simplify small details and express them through color zones rather than defined lines. This is especially the case of background elements, as shown in Image 1. The distant figure running at the top left corner is represented with just black shadows; the soldier holding a dead body is made of yellow, gray and black shades, while only the main soldier has all his features well defined.

To achieve defined contours and smooth gradients, painters may use airbrushes, traditional brushes, and apply several layers of paint, usually reserving the final layer for gloss, special effects, or fluorescent paints (Martinez, 2015). Each painter has their own technique and style; here, we have merely outlined the general characteristics of this craft. Next, we will look at three main trends in picó graphics, keeping in mind that a trend is not necessarily related to any particular time. Many of these ways to conceive and, therefore, do picó painting were adopted and changed simultaneously by different artists and picós.

Image 2. Photograph of the picó El Gran Pijuan. Source: Africolombia

In the image above, we have an example of what can be identified as the first trend of picó painting. In 1967, Maximo Forera laid the foundation of this art by painting the speaker boxes of the sound system El Perro from Cartagena (Barriosnuevo, 2015). After him, Gerson Costa started to achieve fame by combining figurative elements with powerful lettering on the canvas, usually employing a flat background and restrained palettes. Well-known picós that embraced this trend include El Gran Pijuan, El Guajiro, El Nuevo Colonial, El Swing, El verdadero Son, El Último hit, Mister Parranda, El diamante, El solista, El Timbalero, and El Isleño.

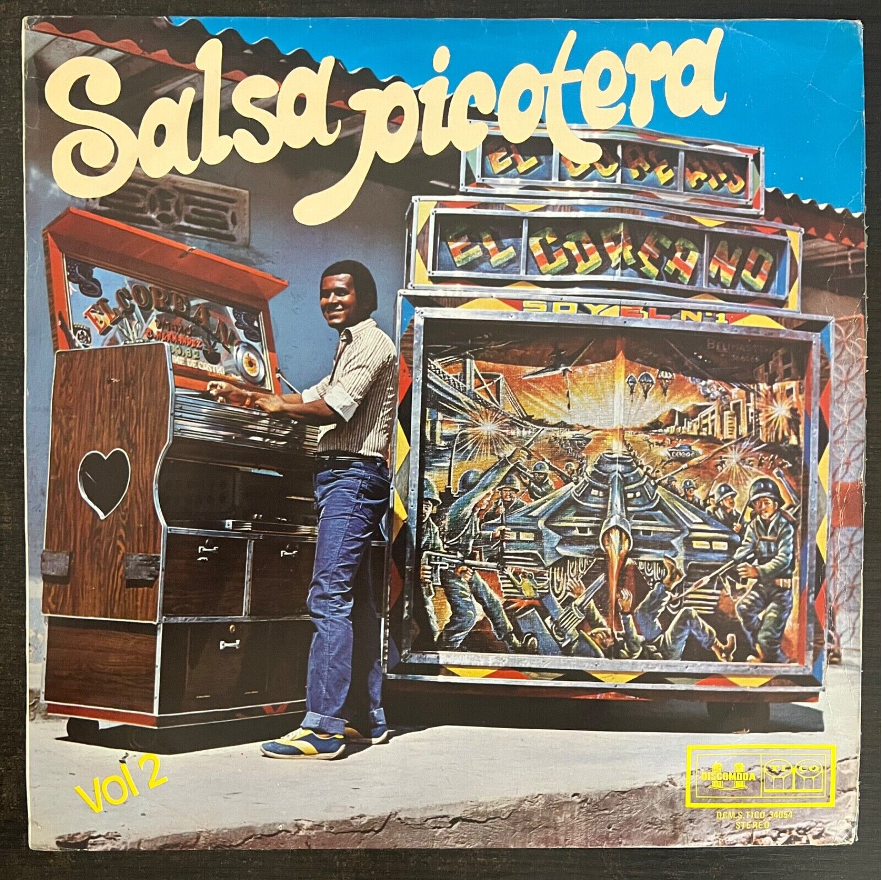

Image 3. Photograph of the picó El Coreano, painted by Belimastth, used as cover image for the LP Salsa picotera Vol. 2 (1980).

The second identifiable trend in picó painting was led by Gerson’s apprentice, the late Belisario de la Mata (Belimastth). The picós he painted often feature more complex scenes. Through the use of landscapes, perspective, and intricate details, the main subject of the painting was given more aleteo by being pictured at the center of a scene where something is happening around him. As the focus is now on the image and its figurative elements, the name of the picó and its slogan were moved to the secondary speakers and margins, resulting in the distinctive text-image separation that is a trademark of today’s picó visuality.

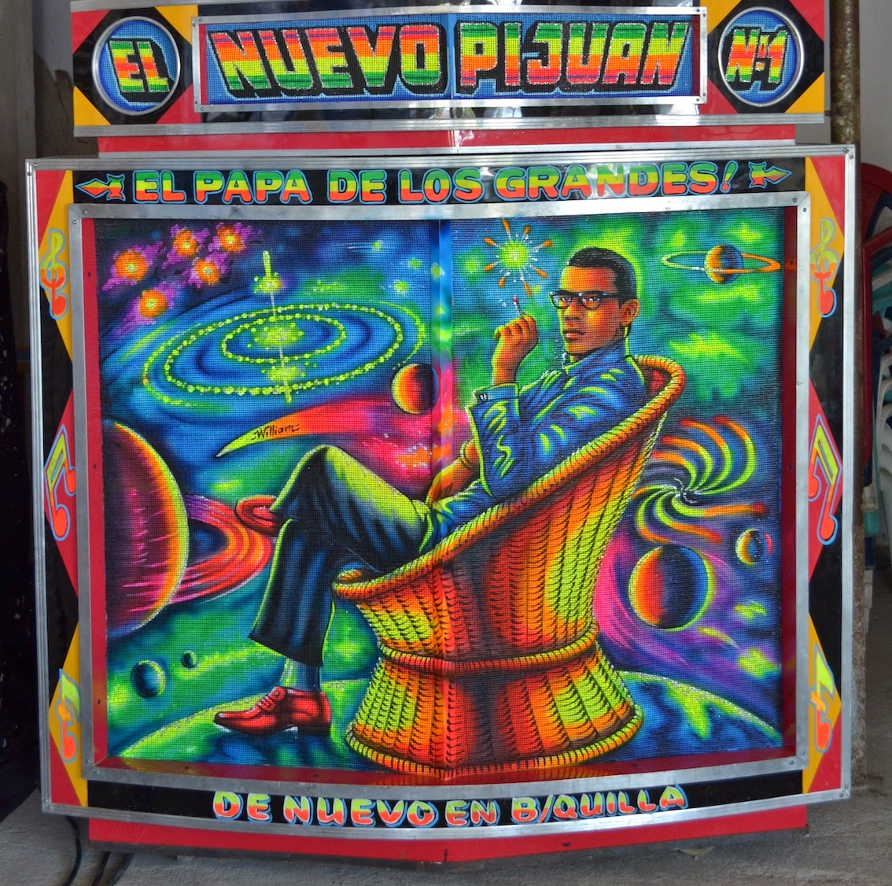

Image 4. Photograph of the picó El Nuevo Pijuan. Source: Fabian Altahona Romero.

The third recognizable trend has been championed by William Gutierrez (Alsanders apprentice), who continued Belimastth´s trend of text-image separation, high density of graphic elements and use of psychedelic strident colors for enhanced contrast, over a black background. In fact, a remarkable characteristic of today’s picó’s technological apparatus is the presence of neon lights within the frames of the boxes with the purpose of improving the visibility of the paintings at night.

“Where there’s no neon it looks dark, burnt out, that’s why we exaggerate with psychedelic colors, because in the places where there’s no fluorescent color it looks non-alive and dark, the white doesn’t shine and that’s why flat or white backgrounds are not used. (…) The colors that stand out the most are: yellow, red, orange, green, fuchsia and the blue ones, the blue palette brightens more under the neon light.” William Gutierrez (2024, Translated by the author).

By analyzing these trends, we can conclude that fuerte [strong] is a crucial adjective in picó culture: strong presence, strong visuals, strong sound, strong names and strong narratives. No picó will ever be humble in an environment where aleteo is everything (Nieves, 2020, p. 62). Keeping that in mind, we’re going to briefly explain two strategies for doing aleteo in picó graphics: boasting and mockery.

On image 5 we find two interesting graphic elements that are often included in traditional picó paintings: frogs and snakes. This is a very explicit case of boasting, since it takes the colombian slang sapo (frog) and culebra (snake) to elevate the prestige and power of the main character (i.e. the picó), who’s crushing not the animals but the people they represent.

“(…) That’s what the snake refers to, the enemy, the culebra, who’s always waiting for the weakness. The frog is the same, it refers to the windbags that are always talking about others. When it comes to picós, one [the picó painter] must always be careful with wha one does because anything can become an excuse for your rival to make a jingle, a satire and mock you.” William Gutierrez (2024; translated by the author).

Image 5. Close up of frogs and snakes painted on El Chileno, El Malembe and El Timbalero.

Mockery is a form of aleteo which is specific to a quarrel between two or more picós. Rather than saying “I’m the best” it means “I’m better than”. This is a common feature of sound system clashes: events commonly organized on the Colombian Caribbean coast, in which two or more picós battle each other for prestige. In this scenario, mockery is a form of aleteo.

“When El Lobo (The Wolf) went to Cartagena for the first time, a jingle was made, an announcement that said «I thought they were going to bring me a Big Bad Wolf, but instead they brought Little Red Riding Hood»” William Gutierrez (2024, translated by the author).

An example of visual mockery through picó paintings can be found in image 6, showing different picó paintings. In the first image (El Gran Elio) a monster is pursuing a drummer who runs out of fear (El Nuevo Latino), while a dragon (El Dragon) is looking at him with envy. On the second painting (El Principe Turbo), a similar dragon has the same jealous look, we can confirm the intention by looking at El Dragon’s original painting, where the three heads of the dragon are looking forward rather than backward. El Principe Turbo includes an additional mockery by portraying the prince’s tiger biting a red cobra, the personification of picó El Rojo (fifth image).

Image 6. Visual references across different picó paintings, in order: El Gran Elio, El Príncipe Turbo, El Nuevo Latino, El Dragón and El Rojo.

After having touched on the techniques, trends and narratives involved in picó painting, we should probably draw our attention to the choice of the subject for the pintura. As the previous examples have shown, it’s common for owners to choose animals, monsters, heroes, celebrities, gods, vehicles, cartoons, amongst others, to represent their sound systems. Do these recurring subjects have anything in common? The answer to this question is not easy, since the reason for a specific theme on the painting may obey trends but ultimately remains the owner’s decision – that’s why it is not uncommon to find portraits of real people on picó paintings.

“There was a time when everyone wanted a war tank as El Coreano, or everyone wanted a guy playing Guitar [as El Solista] (….) Right now in the picós you find trending these super gods like Poseidon or Neptune (…) sometimes they are trending and the clients ask for it: Paint me an image like this or that, and so they end copying the biggest picós, the ones that impose the trend.” William Gutierrez (2024; translated by the author).

It’s important to keep in mind that what we have explored in these blogs are just some of the trends and specific material practices that are common in contemporary picó graphics. The visual language and therefore the engagement in terms of culture is constantly evolving, so it deserves further research. Is aleteo the only practice related to picó visuality? Are these trends, narratives and techniques unique to the Colombian Caribbean? Are there any new technologies and techniques influencing picó’s visual trends? These are some of the questions that might orientate further research.

Notes

[1] Placa is the name for the pre-recorded jingles that are played by the picós during dances. They are used for greeting someone (coba), advertising, boasting and promoting quarrels with other picós. They are recorded by radio broadcasters with very recognizable voices such as Mike Char. They usually include a slogan for each picó and phrases like ¨We have impersonators, not competitors!¨ or (referred to a particular tune): ¨New, exclusive, no one else owns it!¨ (Translated by the author).

References

Barriosnuevo, Dario. 2011. WILLIAM GUTIERREZ: UN MUNDO DE HISTORIAS IMÁGENES E IDEAS, FUKAFRA: Fundación Cultural Afroamericana. https://fukafra.blogspot.com/2011/10/un-mundo-de-historias-imagenes-e-ideas.html

Barriosnuevo, Dario. 2015. Gerson Costa, el iniciador del arte plástico picotero, FUKAFRA: Fundación Cultural Afroamericana. https://fukafra.blogspot.com/2015/06/gerson-costa-el-iniciador-del-arte.html

Gutierrez, William. 2024. Entrevista concedida a Manuel Nieves. https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vQcBNoNH930EJY3vVvDIbwPvIoWt4X3qAUOXwf130HCalrBHLTe7lji5sy2n_hbPA/pub

Martínez Celís, Nestor. 2015. La pintura picotera: Arte singular desde el Caribe colombiano, Arte Actual. https://arte-actual.blogspot.com/2015/01/la-pintura-picotera-arte-singular-desde.html

Nieves, Manuel. 2020. GRÁFICA CHAMPETÚA: Hibridaciones en la producción de identidad visual en el Caribe colombiano. [Undergraduate thesis]. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.12969.31843

Web links

La Typica Sound System’s album

FUKAFRA: Afroamerican cultural foundation

Colombia: Picós – Sound System

The Guardian, small picó gallery

About the author:

Manuel Nieves is a designer and visual researcher (Universidad Nacional de Colombia), he is currently doing his masters degree studying sound system practices involving “pagode” in Brazil (Universidade Federal da Bahia).