Brazilian Funk: A Cry of Boldness and Freedom

Funk: um grito de ousadia e liberdade (‘a cry of boldness and freedom’) exhibition aims to contextualize and celebrate the importance of Brazilian funk in the history of culture in Rio de Janeiro and Brazil at large. The exhibition amounts to 900 pieces of works produced by more than 100 artists, most of them linked to the communities where funk is produced, played and performed, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, objects, photos, installations, and videos. SST Brazil researcher Leonardo Vidigal has explored the exhibition for us. Some musical and cultural aspects of Brazilian Funk and some of the challenges it poses to the SST research have been discussed in a previous blog.

by Leonardo Vidigal

To enter the exhibition “Funk: a Cry of Boldness and Freedom”, the first step is to join a huge but fast queue that leads to a spacious elevator. While waiting in line, we can appreciate a sound wall made of white speaker boxes, (see image above), with the inscription “funk” engraved at the top. The font is the same used by Furacão 2000, one of the most important and long-established crews from the soul music and funk scene (Furacão 2000, 2014): a tribute from the exhibition’s curators and a strong anticipation of what is to come.

Taking the lift, we go up to the exhibition floor at MAR – Museu de Arte do Rio (Rio Art Museum), an old bus terminal that was transformed into a museum by the City of Rio de Janeiro, since January 2021 managed by the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI). It is a mansion from the Empire of Brazil era, connected to a huge modernist building located in the middle of Praça Mauá, a space of great symbolic importance for the exhibition itself.

Paredão (sound wall), tribute to Furacão 2000

In the room next to the elevator we come across two huge projection screens. On the right, we can watch “Our Samba School”, a 1968 documentary by Manuel Horácio Giménez, which shows a parade by the Unidos de Vila Isabel samba school, with the mestre-sala (master of ceremonies) and the flag bearer, children and passersby enthusiastically dancing. On the left, a video of a group of teenagers doing the passinho, the main contemporary Brazilian funk dance move. Those with some knowledge of samba history will know that this Black expressive form began to be known through musical genres such as lundu, which was introduced to Brazilians shortly after the official abolition of slavery in the Empire of Brazil, only proclaimed in 1888.

Brazil was in fact the last country in the New World to proclaim the abolition. Former slaves were dispersed to the outskirts of the main cities, where their religious and musical practices have been systematically persecuted ever since. The location of the exhibition in Praça Mauá is quite significant. In colonial times and during the Empire of Brazil it was known as Praça da Prainha (Little Beach Square) and was close to Cais do Valongo, the port where most of the enslaved Africans arrived, recently excavated and historically rescued. The projections evoke the resemblance between samba and funk dance moves. The display, with the two screens facing each other, makes the choreographic similarities even more evident and suggests historical proximity. The conclusion is that funk suffers from the same prejudice and persecution that samba suffered in Brazil at the beginning of its trajectory, due to the structural racism and segregation still ongoing in this country.

To continue visiting the exhibition, you must pass through a corridor painted with graffiti by representatives from Rio de Janeiro funk communities, establishing yet another connection, this time with hip-hop culture. The idea of the corridor also evokes a literal immersion in funk culture, as if entering a favela dance. In one of the graffiti in the hallway, we read the name of Elza Soares, one of the greatest Brazilian singers who often fused samba and soul music, and the dancer and funk activist Taísa Machado, one of the exhibition’s curators. According to Taísa, “funk is a portrait of the country’s urban outskirts. It is young, bold and marginalized. It is the stage where our voices are heard, where our bodies are seen. It’s where we can show our talent, make money and make our dreams come true. Funk is a dream factory”, she states (Paulo, 2023).

Graffiti-painted corridor to the exhibition

When we leave the corridor, we enter a space displaying animations by contemporary Brazilian artist Biarritzzz based on collages by Maranhão visual artist Gê Viana, who was invited to the exhibition opening. This connection with Maranhão is not casual and it is also part of the SST Brazil research (see previous blog by Ramusyo Brasil at this link).

Gê Viana’s works were created based on drawings by French painter Jean-Baptiste Debret, who from 1816 onwards realistically portrayed Rio de Janeiro, then capital of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves. Rio was the capital because, between 1808 and 1822, the Portuguese kingdom was in fact based in Brazil, as the entire Portuguese royal family, the court, the military officers and all bureaucrats fled Napoleon Bonaparte’s military campaigns and moved to the colony, a unique case in world history (Starling and Schwarcz, 2018). Gê Viana’s collages and drawings juxtapose and mix elements from ancient and contemporary Rio and also Maranhão, such as the huge hats worn by caboclos de pena [1] of Boi do Maracanã (and other bumba-meu-boi groups) and the radiolas – sound systems from this state in the Northeast Region of Brazil (see also the SST Radiolas bibliography at this link).

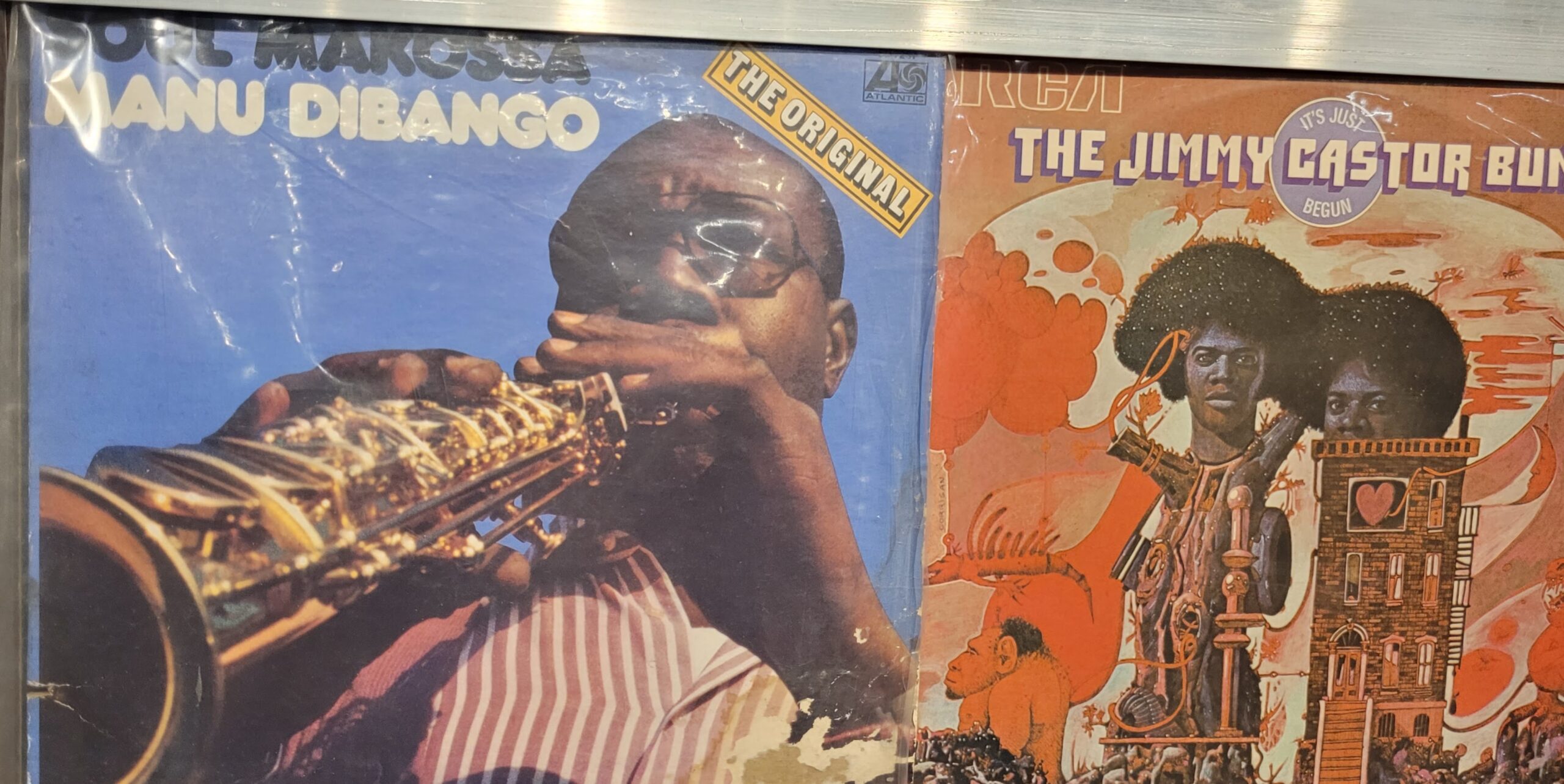

The actual exhibition is divided into two sections. The first one traces the origins of this culture in the Bailes Black, events where soul music predominated, held in the 1970s and 1980s. These were probably the first manifestation of a rising sonic street technologies culture in Brazil, involving huge walls of speakers from crews such as Furacão 2000 (Rio de Janeiro), Zimbabwe (São Paulo) and Soul James (Belo Horizonte) (Laura, 2023), in addition to others from Brasília and other main cities. Youngsters from the city outskirts danced at these parties to the sound of James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Sly and the Family Stone, Manu Dibango, as well as local artists such as Banda Black Rio, Tim Maia, Toni Tornado, Cassiano, Gerson “King” Combo, Sandra de Sá, among many others (Travae, 2021). It was at these parties, such as the Chick Show in São Paulo, where the first Brazilian shows of some of the major soul and funk artists took place, such as James Brown, as well as the first international hip-hop shows in Brazil, such as that of the North American trio Whodini, which the author of this blog attended in 1988.

The curatorship establishes a parallel between the emergence of such dances in the 1970s and 1980s and the appearance of the first entities and groups that promoted racial awareness in the country, such as the Movimento Negro Unificado (MNU), in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Belo Horizonte (Cardoso, 2002), and the Olodum and Ilê Ayê groups, in Bahia, both actively persecuted by the civil-military dictatorship (1964-1985). This connection is reinforced by photos by Januário Garcia portraying black intellectuals and activists from that era, such as Lélia Gonzalez and Abdias do Nascimento. This “nucleus”, as each exhibition segment is called, is the field of Dom Filó, civil engineer, documentary filmmaker, cultural producer, founder of the Soul Grand Prix crew and also one of the exhibition’s curators. He cites the African concept of “sankofa” as his inspiration, according to him a peculiar way of “looking at the past to give new meaning to the future” (OEI Brasil, 2023).

In this area we can see several photos from that era, full color and black and white, portraying the people and the quadras of samba schools and the grassroots clubs where the Bailes Black were held (and some of the funk dances are still held), as well as a profusion of album covers by different artists played on DJ pick-ups at the time. Some strategically positioned sound-totems allowed visitors to listen to a playlist with the biggest hits from the dances. It was common during the exhibition to see people dancing with their headphones on, while enjoying the works of art.

Vinyl sleeves from Bailes Black favourites

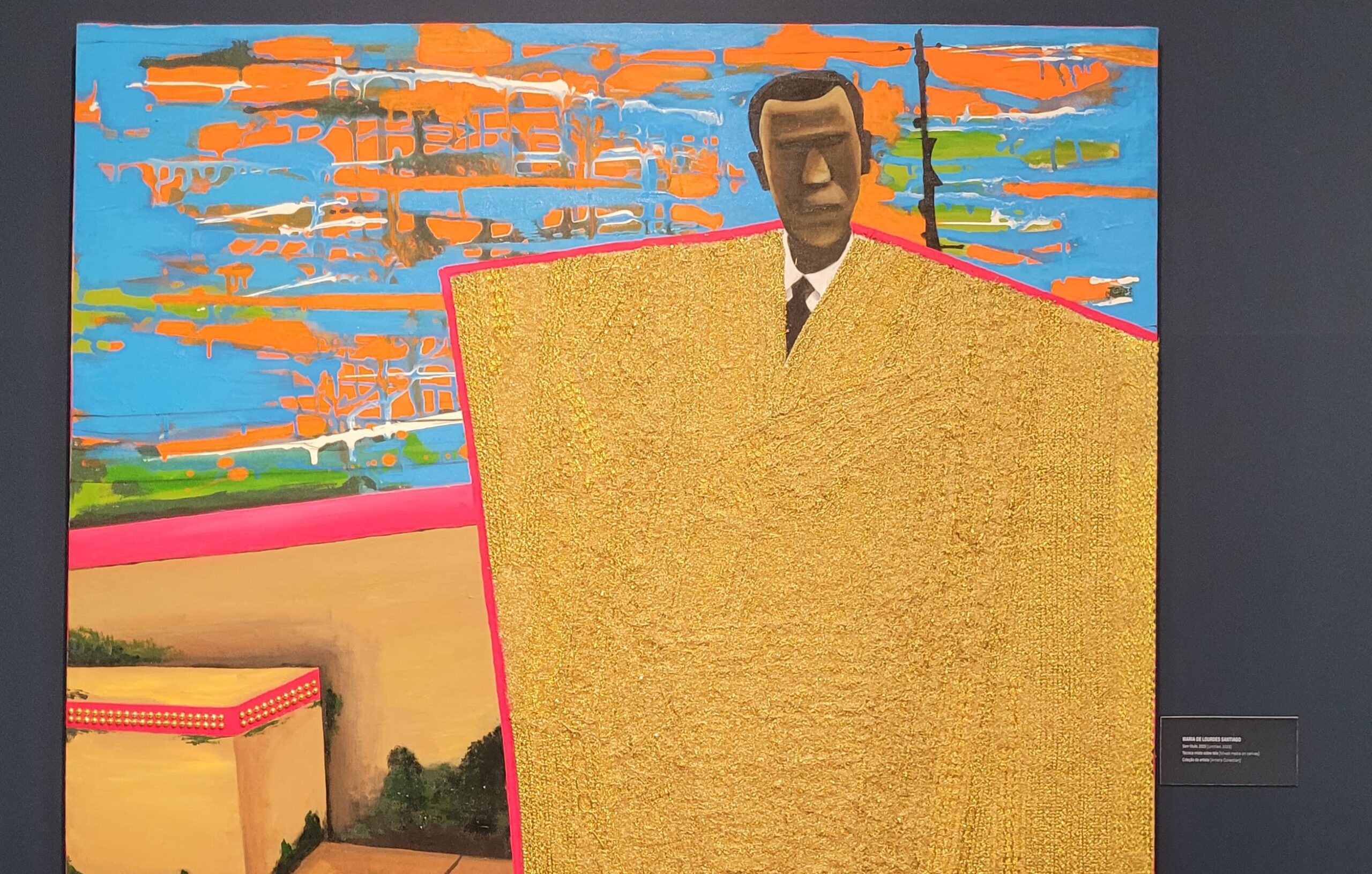

The stylish dancers of soul music parties also appear in works portraying that era, such as this recent painting by artist Maria de Lourdes Santiago.

Maria de Lourdes Santiago, Untitled

The second section of the exhibition celebrates the vitality, visual style and sound of the various manifestations of funk, with an emphasis on Rio’s favelas. But the curation also nods to other places in Brazil and to other music subgenres, such as the battles between groups of brega funk dancers from Recife, in the state of Pernambuco, portrayed in the video “Swinguerra”, by Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca.

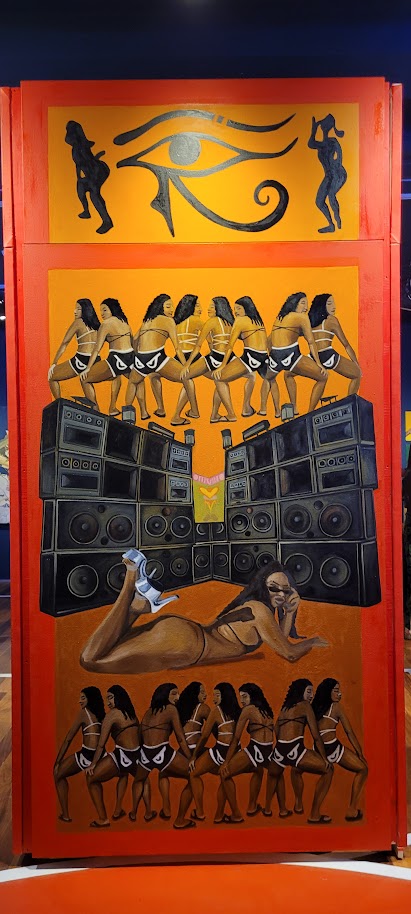

Some works stand out in this section, such as the installation “Relíquia das Relíquias” by artist Thaís Iroko, born and raised on Morro do Chapadão, Costa Barros, in the north of Rio. It is a tribute to the Egyptian Ball (@bailedoegitoofc), which, according to Thaís, “is a dance in my community, and it is the work I bring to this exhibition. […] I already wanted to cross this Egyptian architecture that is in museums, in relics spread around the world, with my research into funk” (Abdala, 2023). The theme of Egypt also appears in the paintings of artist Juan Calvet.

Detail of “Relíquia das Relíquias” by Thaís Iroko

In terms of the sound technology, several photos show the loudspeakers used in the funk parties. These do not look very different from the passive loudspeakers used by old Jamaican sound systems or by radiolas in Maranhão. Speaker boxes also appear in many of the works on display, such as paintings and drawings by Gê Vianna, Blecaute, Thaís Iroko, Guilherme Kid, Herbert and Bruno Lyfe (see artist profiles below).

According to the curatorial team, from the 1990s and 2000s onwards, dances begun to take place not only in clubs and samba school courts but took over the streets with the so-called favela dances. These included huge stages set up in locations more accessible to the community, so that singers, MCs and DJs could perform their music. An entire way of life originated from these dances: a cultural economy completely independent from record companies and music stores (Paulo, 2023). The photography also stands out, showing scenes from current dances, with photos of Melissa Oliveira, Fotogracria, Vincent Rosenblatt, among many others. Segments dedicated to LGBTAQ+ protagonism in funk culture, female empowerment, dancers, amateur football teams from the outskirts and others, made the exhibition more comprehensive and inclusive.

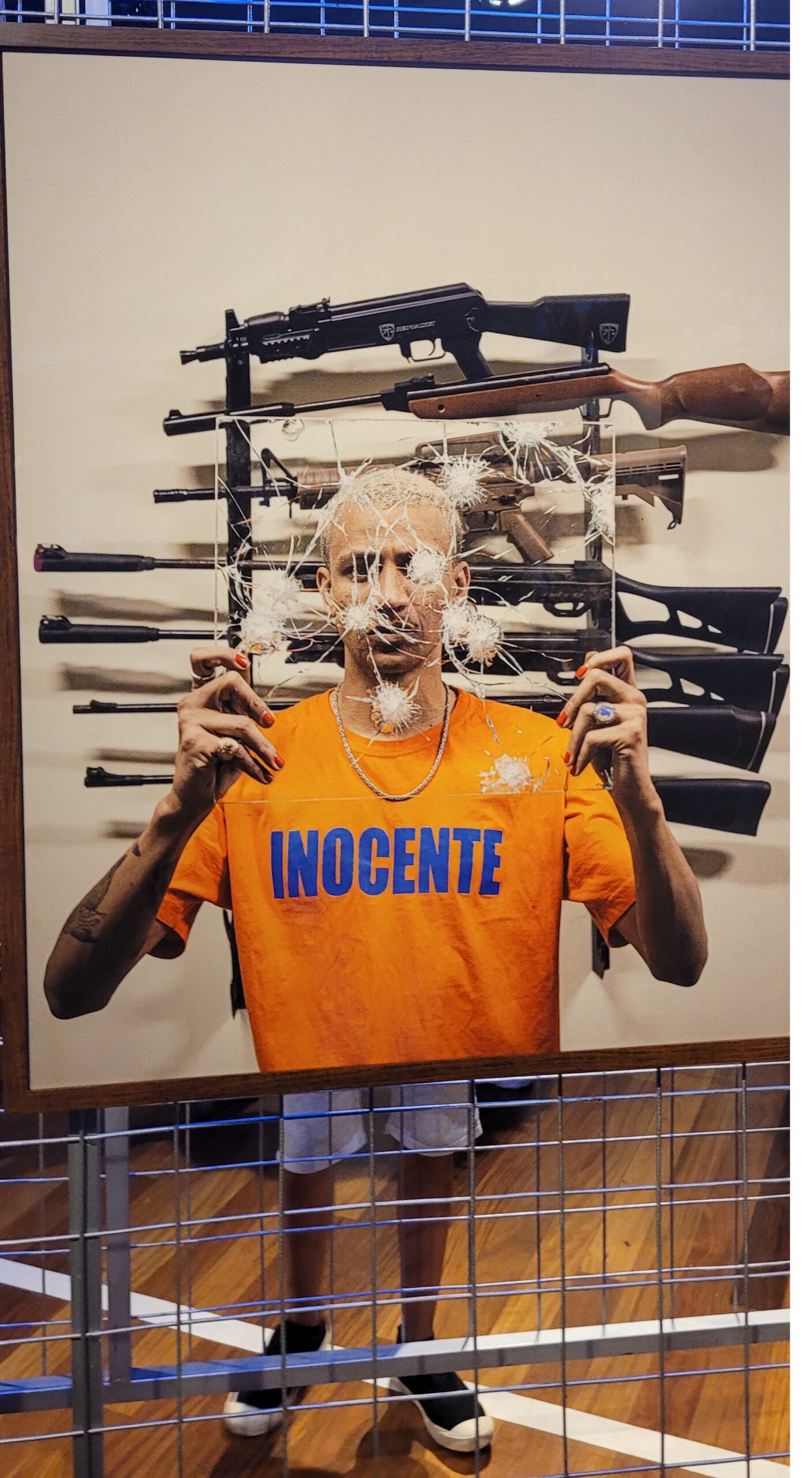

Work by Novíssimo Edgar

The exhibition “Funk: a cry of boldness and freedom” places the funk movement within the sound system culture that developed in Brazil from soul music dances and is a powerful antidote against the deadly poison of racist genocide and epistemicide practiced against the Black population in Brazil. It is also a good opportunity for many people to begin to see and hear funk “as art and only as art, without the need for additional justifications”, to obtain “full citizenship” and as a basis for building “affective communities” (Muniz, 2015, 2016) and, why not, sonic communities. It is an almost perfect introduction to the study of Brazilian funk machines as sonic street technologies.

Leonardo Vidigal is Professor of Film Studies at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil. He is also a founder of Sound System Outernational research group, and a member of Sonic Street Technologies team and Deskareggae Sound System team.

—

Exhibition Info:

“FUNK: UM GRITO DE OUSADIA E LIBERDADE”

Museu de Arte do Rio, Praça Mauá, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

The exhibition is on until the end of July 2024. Curation by Marcelo Campos (@marcelocampos7825), Dom Filó (@dom_filo) and Taísa Machado (@afrofunkrio), with curatorial assistance from Amanda Rezende (@amandinharezz), Jean Carlos Azuos (@umcuradorjovem), Gabriel Moreno, Thayná Trindade (@trinthay), Thiago Fernandes, Waleska Oliveira (@iamwaleska), consultancy by Deize Tigrona, Celly IDD, Tamiris Coutinho, Glau Tavares, Sir Dema, GG Albuquerque, Marcelo B Groove, Leo Moraes, and Zulu TR. The exhibition was carried out by the architects of Estúdio Gru.a. @grua_grupodearquitetos. Light: Diana Joels @dijoels and Luana Alves. Cenotechnics: FR scenography @frcenografia .

Links:

Social media profiles for artists cited:

- Januário Garcia – @januariogarciaoficial

- Juan Calvet – @CddlRylrXCB

- Gê Vianna – @indiiloru

- Herbert – @artedeft

- Guilherme Kid – @guilherme_kid

- Fotogracia – @afotogracria

- Bárbara Wagner – @barbarawagner

- Bruno Lyfe – @bruno.lyfe

- Melissa Oliveira – @melisssadeoliveira

- Manuela Navas – @navas_manuela

- Maria de Lourdes Santiago – @0mmlu

- Emerson Rocha – @de.saturno

- Thiago Ortiz – @ortizth

- Thaís Iroko – @princesinhaperiferica

- Blecaute – @6lecaute

- Deize Tigrona – @deizetigrona

- Novíssimo Edgar – @novissimoedgar

Further content:

- Trecho de Swinguerra by Bárbara Wagner, Benjamin de Burca: https://vimeo.com/414733279

- Nossa Escola de Samba documentary (English subtitles): https://vimeo.com/245369417

- Official Exhibition Launch: https://youtu.be/-qV7vRsftVk?si=qcV2w3DOQjlTtha1

- Virtual Tour: https://youtu.be/LcfyxXyUnpE?si=ahnAI3Ipcx2kAImK

- Canal Curta! feature: https://youtu.be/ajhKj1eqDPY?si=v8D62UU58VBZSjYh

- More images from the exhibition: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/search?term=funk.

Notes

[1] “Caboclo de pena” can be translated as “feather caboclo”, because the big hat they use is made of feather. “Caboclo” is the name given in the colonial era to the mixed-race (born of a white or European person and a indigenous or native Brazilian person) son or daughter (“cabocla”) which is now the most common ethnic type in Maranhão. A caboclo de pena is a dancer in a specific type (or “accent” – there are five types of bumba meu boi groups in MA, according to the instruments used in the music making : “matraca”, “orquestra”, “zabumba”, “costa de mão” e “baixada”, the feather caboclos are more common in the “matraca accent”) of bumba meu boi group, a folkloric group that is often associated with the radiolas.

References

Abdala, Vitor. Funk vira tema de exposição em museu carioca. Agência Brasil. Disponível em: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/geral/noticia/2023-09/funk-vira-tema-de-exposicao-em-museu-carioca. Acesso em 02/11/2023.

Cardoso, Marcos Antônio. Movimento Negro em Belo Horizonte: 1978-1998. Belo Horizonte: Mazza Edições, 2002.

Furacão 2000 – Funk de Verdade. Canal Furacão 2000. 22 de dezembro de 2014. Disponível em: https://youtu.be/Gn44q-NkP2E?si=l1jr5Hwj_jacqsuj. Acesso em 02/01/2024.

Laura, Brenda. As mulheres do soul dançam muito. Revista BDMG Cultural. No 11, 30 de setembro de 2023. Disponível em: https://bdmgcultural.mg.gov.br/artigos/as-mulheres-do-soul-dancam-muito/. Acesso em 10/01/2024.

Muniz, Bruno Barbosa. Quem precisa da cultura? O capital existencial do funk e a conveniência da cultura. Sociologia & Antropologia (02) 02. p. 447-467, Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 2016

Muniz, Bruno Barbosa. An affective and embodied push to Bourdieu’s dispositional model: Funk’s cultural practices in Rio de Janeiro. Tese de doutorado, London School of Economics and Political Science. London: LSE, 2015 Disponível em http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/3384/. Acesso em 01/25/2024.