Black Music in Britain in the 21st Century

ST is always ready acknowledge scholarship exploring black music and technology. As well as well as the work of sound system and other professionals, researchers also have a valuable role to play in helping to give recognition and respect to the creativity that often starts at street level.

Dr Monique Charles is an inspiring Black female academic, always repping Grime and Black urban youth culture both within the academy and outside of it. Monique’s editing and work put into the pulling together of the book is admirable and a much-needed boost for literature on Black British music. Throughout 15 chapters on topics ranging from Dub to jungle to jazz, the books charts where Black British music comes from, and how it has arrived in the 21st century. As a team, we are pleased to showcase the book through Monique’s personal thoughts and reflections on the process.

by Monique Charles

This book was published in March 2023. I am the creator, curator and editor of Black Music in Britain in the 21st Century. This edited volume is long overdue: almost 5 years in the making. My interest in creating and curating this project has an organic and lifelong route. Now, I am a Black British academic (currently located in the USA – Assistant Professor of Sociology at Chapman University). I am a cultural sociologist, theorist and methodologist. I am also a sound therapist and cardologer. My background and its connection to this book, is rooted in my desire to sing as a child. I used to sing and write songs and poetry and I would encourage my cousins to join in. Growing up in London, I was very aware of the music that I liked and the music I listened to at home and with family was very different to the music that was on mainstream television and radio stations.

Intellectually, I pursued both these interests from undergraduate level onwards. On the journey, I became motivated to contribute to consolidate the position of Black British music into the academic conversation and ultimately into building a discipline around Black British music – for it to be considered as something of serious intellectual inquiry. From my PhD on Grime [1], I developed a methodological framework known as Musicological Discourse Analysis (MDA) [2]. This is a research method that can be applied to analyse music for the Social Science and Cultural Studies fields. I also developed AmunRave theory [3], which explores what happens in life performance spaces metaphysically/spiritually. In my PhD, I outlined the chasm that Black British music fell within in the British academy in the field of music. Music was often structured in Classical or Ethnomusicological terms. Any popular Black music forms were often positioned as being outside of Britain.

Alongside my personal journey and since the turn of the 21st century, there have been several genres birthed or gaining recognition in Black Britain, such as funky & tribal house, afrobeats, grime, afro swing, drill, trap etc. I believe we are experiencing a British ‘Renoirssance’ (Black Renaissance) [4]; plentiful Black musical, literary and cultural creativity that possibly for the first time is supported and sustained by an increasing body of scholarly and intellectual work and business infrastructure. Through this book, I expand upon Gilroy’s concept of ‘routes and roots’ (1993) [5]. This book explores the shaping of British music through Black Atlantic culture and proposes that global interactions and formations are now sustained by ‘roots, routes and routers’ to include the significance of the internet and digital world in the process.

Creator, curator and editor Dr. Monique Charles holding a copy of Black Music in Britain in the 21st Century. Photo by Monique Ingalls.

The vastness that is Black British Music cannot be covered in its entirety here. Importantly, it is a significant contribution to advancing the subject as being of serious intellectual enquiry and the discipline more broadly. This is something I felt compelled to do owing to my desire to being the change I wanted to see. This book is firmly rooted in the sociology and cultural studies field. I invited each contributor to take part in the project. Although her area is Law, I invited Mry W. Gani onto the project. She co-edited one chapter. Each contributor who offered a narrative to this edited collection make a significant contribution towards documenting and incorporating Black music in Britain into the cannon. The collection is divided into three broad themes: Diaspora music & The Black Atlantic, 21st Century Black British Music and Socio-Political Economic issues.

The first section is Diaspora Music and the Black Atlantic to acknowledge the 21st century Black British culture’s symbiotic relationships between Africans on the Continent and in Britain, as well with the Caribbean [6]. Additionally, Black British culture is exposed to African American culture [7] which has had a role on Black British identity and music [8] [9].

In Dub Come Save Me, Natalie Hyacinth explores the Dub remix album of Manuva’s 2001 hip hop album, Run Come Save Me. My chapter RWD Selecta outlines Jamaican music and cultures ‘sound system sensibilities’ in a framework comparable to hip hop ‘elements’. Lawrence Johnson’s chapter that I co-edited with Gani, reflects on his involvement in Black British Gospel Music for over 40 years. Nathaniel Telemaque’s photo essay Trap Atlantic captures the distinct Trap sound and visual aesthetic; visualising the culture of Trapping on both sides of the Atlantic.

Photo by Glodi Miessi on Unsplash

The second section is 21st Century Black British Music that explores new genres of music that have emerged through Black British sociological interactions and cultural exchange. It considers older 20th century genres that have maintained into in 21st century Black British cultures.

In Hopelessly In Love, Lisa Palmer interviews Carol Thomson, veteran artist of the British lover’s rock reggae scene about a career spanning over 40 years. Julia Toppin’s Critical Intersectional History of Jungle outlines a critical history of Jungle at the intersection of race and gender to provide a holistic historical account of the genre. Pauline Muir’s chapter Black Majority Churches and popular music uncovers the experience of learning and playing music in the demanding praise and worship environment. Caspar Melville’s Today’s Warriors: British Jazz in the 21st Century examines the significance and nuance of British Jazz and the ways in which it has been sustained, consumed, shared and enjoyed in Britain. Michael Ugwu’s From London to Lagos recounts his experiences as a British Nigerian, Music Executive and his involvement in the West African music industry ranging from independent start up to major record label, with a special focus on the London-Lagos relationship. Hannah Charles and Andrew Facey’s photo essay captures Mangrove Steel Band in a variety of performances.

The final section is Socio-Political and Economic Issues in Black music. In this section frameworks and propositions build new ways to engage, understand and interact with Black music in Britain and the value it has to wider British society and beyond.

In Roy Wallace & Daniel Johnson’s Sounds of Oppression they argue the crisis in mainstream Black British music, concerns the ‘invisibility’ of Reggae music, its pioneers, artists, DJ’s and musicians that have made and continue to make major contributions to Black British music. Lambros Fatsis’ Arresting Sounds proposes new frameworks through sound system culture to interrogate policing and institutional racism. Cheraine Donalea Scott’s Grime Practice as Refusal explores the internal gender and sexual politics occurring within the British Grime scene as well as the politics of Black quiet. Silhouette Bushay’s Public Pedagogies of Resistance focuses on the racialised gendered dimensions of British Hip Hop and Grime (BHHG) music in relation to Black British women, society, politics and economics and explores how Black women take up space in Black male dominant music genres, the public realm and psyche. Lastly Poonam Madar’s Ways of Seeing: Black male identity(ies) and the politics of Black music, examines the significance of looking and seeing in the context of Black British masculinities and Black music.

Photo by Marcela Laskoski on Unsplash

Some of these genres origins predate the 21st century, but it is important to bring these genres into conversation, because they are very much still alive with active engagement from their respective scene members in current times. When we think of 21st century Black British music we think of more obvious genres such as grime and drill. But there are legacies that these older genres borne before the 21st century bleed into the 21st century. Additionally, some of the genres have gained resurgence amongst a new generation, such as jungle and jazz, others continue to evolve such as gospel and ‘bleed’ into popular music more generally. The book provides veterans and experts of pre 21st century Black British music, the opportunity to reflect and provide their narratives (as a comparator that either they or the author bring to the fore). It enables the reader to make connections to where we are in the 21st century – what happened to the music, scene or the people? Other chapters around frameworks and concepts may provide new insights to these ‘older’ genres as well. In terms of why they are lesser known now, or factors that may have influenced their trajectory.

The main processes, thoughts, concepts for the book are firmly rooted in sociology and cultural studies. Music is sound but it is also social. Music isn’t just vocational. I wanted to bring together conversations about the African diaspora and music in a more contemporary context. There are social, cultural and political shifts that have taken place that are evident in music. There is so much practical, embedded, and embodied knowledge ‘on the ground’. Having networked extensively, I contacted and worked with the contributors, knowing their areas of expertise and the value their narratives could add to the project.

I want the book to appeal to musical ‘nerds’ as well as for undergraduates and postgraduates. For this reason, the book is more than a series of essays. There are some essays – some of which explore concepts and frameworks. Some tell or interrogate a narrative. Some provide visuals. Others provide a conversation (that I transcribed) or center the voices of people in their related scenes. I created it this way so readers could have a broader view of Black British music in the 21st century. They could enter at whatever level they feel most comfortable. They could focus on any of the genres included in the book. Some chapters can even be used as primary data.

Together this edited collection is a powerful opening into a new era of discipline development with regard Black British Music. It is the hope that the book and corresponding jiscmail BlackMusicinBritain@jismail.ac.uk become hubs to engage, share and collaborate as the discipline itself continues to grow.

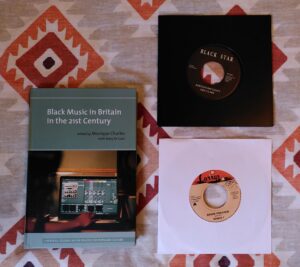

Dr. Fatsis’ author copy of the book alongside some records that inspired his chapter.

—

Monique Charles (https://drmoniquecharles. com) is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Chapman University, California. She completed her PhD at Warwick University focusing on “race”, spirituality, class, gender and music as it relates to grime. Her research highlights her interest in music, spirituality, sociology and the African Diaspora.

References:

[1] Charles, M., (2016) Hallowed Be Thy Grime?, Doctoral Thesis. The University of Warwick.

[2] Charles, M., (2018) “Musicological Discourse Analysis”, IJQM.

[3] Charles, M., (2019) “Grime & Spirt: On a Hype”, Open Culture.

[4] Charles (2023) “Introduction” in Black Music in Britain in the 21st Century. LUP.

[5] Gilroy, P., (1993) The Black Atlantic. Verso.

[6] ‘Lez’ Henry, W., (2012) ”Reggae, Rasta and the Role of the Deejay in the Black British Experience”, Contemporary British History, 26:3, 355-373.

[7] Rose, T., (1994) Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press.

[8] Reynolds, T. (2007) “Friendship Networks, Social Capital and Ethnic Identity: Researching the Perspectives of Caribbean Young People in Britain”, Journal of Youth Studies, 10(4), pp. 383 — 398.

[9] Gilroy, P., (2004) “It’s a Family Affair” in Foreman, M. and Neale, M. (eds.) That’s the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. Psychology Press. pp 87 – 94.