Lost in Transition. When Sonic Street Technologies Go Digital

This piece examines several aspects of the pandemic-driven digitalization of sonic street technologies scenes, aiming to understand ongoing and potential shifts in the affective and monetary economies of street sonic cultures. Its purpose is to gain deeper insight into the unique features of sonic street technologies, while also offering a fresh perspective on systemic changes in the relationship between technology and culture.

by Brian D’Aquino

Social distancing, lockdowns, and curfews have brought the entire music industry to an indefinite halt. Reggae sound systems and other sonic street technologies have been among the hardest hit, given the very nature of the experiences they provide. Their operations, often in public spaces, usually after dark, and straddling the line between legal and illegal regimes and economies, place them in a ‘grey zone’ where compliance with state regulations is frequently difficult. In most cases, this has either excluded them from the tentative (and heavily policed) re-openings or exposed them to criticism for non-compliance (1).

Dance prohibition sign, Italy 2021. Covid-19-related dancing ban is still in place in the country.

In the meantime, practitioners and punters have turned to social media and streaming platforms to cope with restrictions, stay connected with their sonic comrades, and find relief from the harshness of an uncertain present by gathering virtually in the COVID-free space of the World Wide Web. But what happens when a street-based sonic culture is abruptly forced to jump into the digital realm?

From analog to digital experiences

Obviously, the digitalization of music is nothing new. Over the past century, music has frequently migrated across storage media—cassettes to CDs, minidiscs to pen drives—culminating today in the ubiquitous archive of Spotify. What is arguably new is that it is not the music itself but our experience of it to be digitally mediated. The proliferation of live music streaming has helped to transcend continental boundaries and keeping people together in challenging times. But it has gone hand in hand with the proliferation of a solitary, home-based, small-speakers-powered listening experience.

The drive toward an intimate, domestic experience of recorded sound—backed by capital’s aim to turn every music lover into a paying customer—has long been a key force in the development of sound technologies. Yet this trajectory has always been counterbalanced by an equally strong impulse to enhance immersive sound experiences and the joy of collective listening. With gatherings temporarily deemed personally risky, socially unacceptable, and often illegal, the ghost of a forced digital transition now haunts the global dancefloor of sonic street technologies. As we wait for sound systems to hit the streets again, it is worth considering this virtual interlude as a window onto possible futures and an opportunity to raise a question: what is lost in the digital transition, and who is left behind?

Intensity Shortage

What is immediately lost is the shared, multisensorial, physical experience of sound, which Julian Henriques aptly names sonic dominance:

“the visceral experience of audition, to be immersed in an auditory volume, swimming in a sea of sound, between cliffs of speakers towering almost to the sky, sound stacked up upon sound” (2).

Sonic dominance as auditory overload is intimately tied to intensity. Yet it should not be reduced to mere loudness. In other words, the power of sound to subvert the hierarchy of sensorial regimes lies beyond what can be measured – in decibels or through led lights. Sonic dominance as a carefully induced state of altered consciousness that engages the embodied self as both individual and collective being is enabled by a sophisticated understanding of sound, expressed through the precise engineering of vibration, which forms part of the sound system operator’s embodied knowledge. It emerges from an acrobatic play at the threshold between sound and noise, where “pushing into the red” produces pleasure rather than pain. And here lies the challenge.

Analog vu-meter heading towards red.

Since the early 1990s, fourth-generation music software has suddenly endowed thousands of amateur producers with superhuman computational power, inaugurating an era of hyperrhythm: “posthuman rhythm that’s impossible to play” (3). While the digital environment opens up an infinite field of rhythmic possibilities, at the same time it reins in intensity—a vital dimension of sonic street technologies—and its modulation as a strategy of affective mobilisation. Tempo can be endlessly broken down into micro-rhythmic units and recombined at will, but intensity resists computational logic, which remains primarily calibrated to loudness. In other words, pushing digital sound waves into the red generates neither pleasure nor pain. The sonic overload is simply registered as error, and rendered as the vaguely annoying—but wholly un-affective—digital clip. Stripped of analogue machinery and embodied transducers, intensity is lost in transition.

Lone Islands in the Net

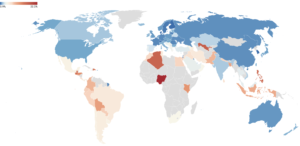

Another burning issue is that of the accessibility and the reach out. According to the Alliance for the Affordability of Internet (A4AI) 2021 report, the cost of 1GB should be less than 2% of yearly income. Unfortunately, this is not the case in several countries. The cost of internet connection, exacerbated by the financial straits caused by the lockdown and the need to prioritize information and communication over entertainment, can make a streaming session a luxury for many.

The issues of the digital divide and the unequal access to the internet has resonated strongly throughout the online symposium SSO#7: Sound Systems at the Crossroads, and especially during the practitioner’s roundtable entitled The Sonic Challenge: Post-Pandemic Sound System Practices, held on 9 July 2021. For example, although proudly celebrating their virtual community, the all-female Brazilian crew Feminine Hi Fi noted how the access to music streaming has been virtually neglected to the people living in Sao Paulo’s favelas, where some of their crowd dwell. While Doc Inity, who runs Kebra Ethiopia sound system in Kwa Thema, South Africa, has highlighted the paradox of his virtual sessions reaching more European followers than local residents—the very same people who usually pack his street dances.

These are just two examples of isolated islands within a wider digital archipelago of blind spots on the net. Rooted more in lack of financial means than in technological capacity, these gaps undermine the supposedly unified (and unifying) narrative of the World Wide Web as an inclusive space of possibilities, instead reproducing the same boundaries that constrain the offline lives of the underprivileged in global society. It is precisely those who inhabit such high-pressure environments—the soil from which sonic street technologies continues to bloom—who are left behind.

Free Entertainment or Free Labour?

But the most challenging issue surrounding SST in the online world is undoubtedly that of wealth production and distribution. During the lockdown music producers and artists have been kept afloat by dubplates recordings, record sales and streaming revenues. In this respect, a successful online performance can be immediately monetized. One notable example is the Bounty Killa x Beenie Man clash hosted by IG channel Verzuz TV in May 2020, which drew an audience of 500k viewers, and trended globally on Twitter. Both artists experienced the best Spotify streaming days of their careers immediately after, with a 187% increase for Beenie and an impressive 291% for Bounty.

Full Bounty Vs Beenie tracklist repacked by Spotify as a trending playlist.

Sadly, for sonic street technologies there is no product to be advertised through online performances: playing music is itself the product. The lockdown thus deprived practitioners of their primary source of income, leading to what veteran Jamaican soundman and Stone Love owner Winston ‘Wee Pow’ has described as “the most challenging of times”. For them, the rewards of a virtual session can only be reaped, at best, in the post-pandemic world—not exactly a viable way to put food on the table. Nonetheless, many have embraced the cause with remarkable generosity.

Bredda Neil of King Shiloh sound system and crew have been streaming from their Amsterdam HQ on their FB page every single Saturday for 77 consecutive weeks so far. Aptly titled ‘Healing of the Nations’, these sessions have uplifted thousands of fans since then, and have collected more than 100k views on King Shiloh’s YouTube channel, where they have been archived since January 2021.While YouTube views can be monetized through ads, they generate significant income only at very high numbers—typically in the millions—far beyond the reach of even the most established sound system practitioners. Yet beyond the numbers, it is ultimately the business model of digital platforms that demands scrutiny.

During the late-1990s internet craze, a few critical voices warned that the ultimate aim of all the “free stuff” online was simply “to have you consume bandwidth” (4). Twenty-odd years later, with the cost of bandwidth steadily falling, such claims may sound naïve. Yet they were onto something. The shift to Web 2.0 ushered in the rise of platform capitalism (5). The corporations competing in this arena do not sell products; their business model rests almost entirely on data harvesting. The notion of “free labour”—with “free” meaning “simultaneously voluntarily given and unwaged”—once applied mainly to forum moderators, code developers, and mailing list participants (6), can now be extended to virtually every web user. The objective is simply to have people spend more time online, so that more data can be extracted. Put differently: online presence itself generates wealth—wealth that is captured primarily by the platforms.

King Shiloh’s ‘Healing of the Nations’ n. 77, August 2021.

In fact, platforms like YouTube (ads), Twitch (subscriptions), Buy Me a Coffee, or Facebook Stars offer music and sound practitioners—generically rebranded as “content creators”—ways to monetize their free labour. Yet they do so by shifting the burden onto the audience, both by saturating music with ads and by inviting fans to pay directly out of pocket. It is time to demand a fair share of the wealth that online presence generates—starting with so-called “content creators,” whose contribution to platform value extends well beyond ad revenue to include the “network effects” (7) that sustain the entire ecosystem, and extending down to casual users. The pathways forward are still to be imagined. But who provides the flour should be entitled to a slice of the cake, isn’t it?

SST as media ecologies

It is also crucial to understand sonic street technologies as complex entities that cannot be reduced to the music they play or the individual operating them. Rather, they are socio-techno-cultural apparatuses—collectively operated phonographic and sonic media in their own right. As such, they exist within a broader ecology of other media, bodies, affects, and cash flows, which they help generate and fine-tune. This media ecology (8) sustains many participants, from the box-lifter to the peanut vendor. Yet by adopting the platform’s close-up as the default perspective—focusing primarily on content creators—there is a risk of losing sight of the bigger picture, and of leaving the most vulnerable figures in the scene behind.

In the rapidly shifting context of forced digitalization prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the most urgent need for SST is to escape capture by platform capitalism by parasitizing digital infrastructures in the same way they have successfully done with analog technologies and urban environments. After all, sound systems have unexpectedly turned the domestic turntable into a performing instrument, infused the experience of listening to recorded music with the pathos of theatre, and transformed dodgy street corners into coveted dancefloors. What they might achieve in the digital age remains to be seen.

—

Brian D’Aquino is Senior Research Assistant in the SST project. He’s an author, sound system practitioner and music producer based in the Southern side of Europe.

—

References:

(1) This is the case with the free tekno party hold Rennes, France, on New Year’s Eve 2021, or with the Space Travel Teknival held in Viterbo, Italy, in August 2021, among others.

(2) Henriques, Julian. 2011. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques and Ways of Knowing. New York-London: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. xv.

(3) Eshun, Kodwo. 1998. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet, p. 068.

(4) Horvarth, John. 1998 “Freeware Capitalism”. Posted to nettime, 5 February, https://nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9802/msg00026.html

(5) Srniceck, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge-Malden: Polity Press

(6) Terranova, Tiziana. 2000. “Free Labour: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy.” Social text 18.2, p. 33-58

(7) Srniceck, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge-Malden: Polity Press, pp. 43-45.

(8) Fuller, Matt. 2005. Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.