SST Final Year Report for 2025

As usual, we begin the new year of blogging with some broader considerations regarding the direction, achievements, and challenges of the SST research project, alongside some of the highlights of the previous year. The difference this time is that 2025 marked the final year of SST in full operation, as the project reached the end of its funding period. However, as we continue the editorial work for the Mobile Music Machines book series, the website will remain live, including the blog, the Sonic Map, and the YouTube channel, and further events are in the making.

We may have come to the end of the SST ERC research programme, though this is certainly not the end of the project—that is, opening up the field of sound system cultures and technologies. In fact, this began even before SST with Sound System Outernational (SSO) in 2016, and it will continue from now on. As intended, this final year of the five-year SST project has focused on gathering research write-ups for publication rather than initiating new work. The first volume of the Mobile Music Machines edited collection should be delivered shortly to Bloomsbury Academic, our publishers.

SSO#11 Sound System Cultures Worldwide

The main event of the year was undoubtedly SSO#11 Sound System Cultures Worldwide, which served as the end-of-project SST conference. David Katz did his usual excellent job of giving an account of the SSO#11 event. With twenty-three presentations—many accompanied by films—each of the soon-to-be book chapters across the four volumes had the conference’s full attention. This was only the second time, after our global team meeting in Jamaica in February 2024 at the Global Reggae Conference, that the SST team had been in one place, albeit for some, virtually.

SS0#11 Conference room

Over the two days, the overall scope of the project was clearly in evidence, as were the many connections between the different research projects around the world. As might be expected—but also as a pleasant surprise—for some members of the global team, their understanding of the project began to make sense in a way they had not been able to imagine until this near-end point. For the Goldsmiths team, it was very satisfying to hear that the novelty of our approach had initially been a challenge but was now being taken up and embodied by members of the global team.

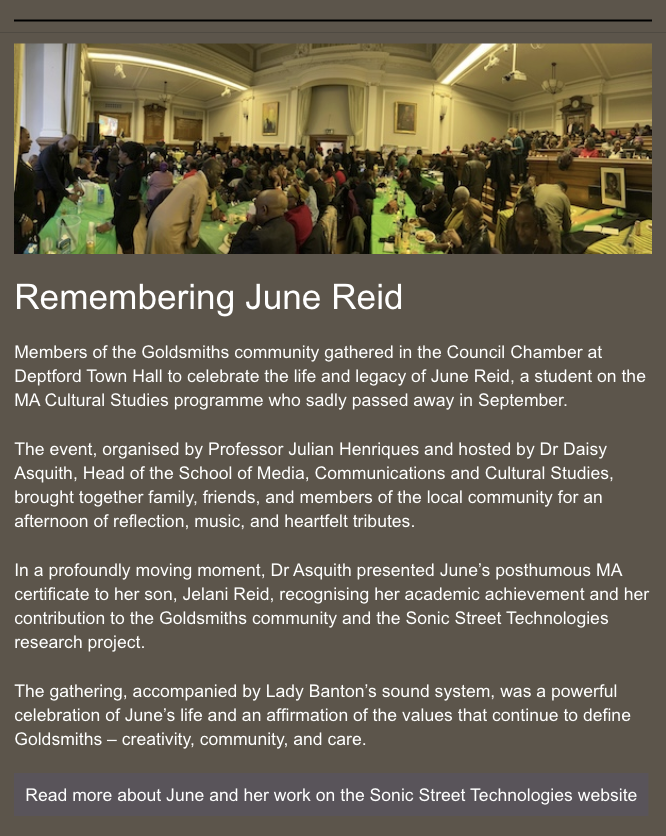

June Reid, aka Junie Rankin

Another notable event of the year, though far less pleasant, was the passing of June Reid, aka Junie Rankin, a beloved member of SSO. She was also an MA student at Goldsmiths, having chosen to pursue an academic career later in life in order to equip herself with the tools to explore her personal history as one of the female pioneers of sound system culture in the UK with Nzinga Soundz. Due to her illness, she was unable to complete her studies, but the College awarded her a posthumous honorary degree. June’s contribution to both SSO and SST has been immense, and we are absolutely committed to honouring her legacy by continuing the research to which she was so deeply devoted. You can read about June here.

From Goldsmiths weekly newsletter, 19th November 2025

This final SST annual report is an appropriate place for some reflections on the achievements of the project. Our most significant research ambition has been the establishment of sonic street technologies as a novel area of research. While street music cultures of the Global South have received some attention in their countries of origin—though far less so in English—the SST project was designed to address what we identified as a distinct gap in the existing literature. There remains a substantial lack of research on the relation between phonographic technologies and subaltern cultural formations in the Global South. This absence has helped to reinforce false assumptions: that the distinctive sound system equipment originating in marginalised communities has nothing to tell us about technology, and that the skilled techniques and knowledge systems involved in designing it have nothing to contribute to understandings of cultural creativity.

Filling this gap in the existing research has involved nothing less than fine-tuning a research methodology in which the practitioner’s own experience is valued as a specific, situated form of knowledge. This has initiated collaborative research pathways in which the practitioner’s contributions take centre stage, ensuring that the research itself benefits local scenes and fosters broader recognition of the culture’s struggles and achievements in the local environment.

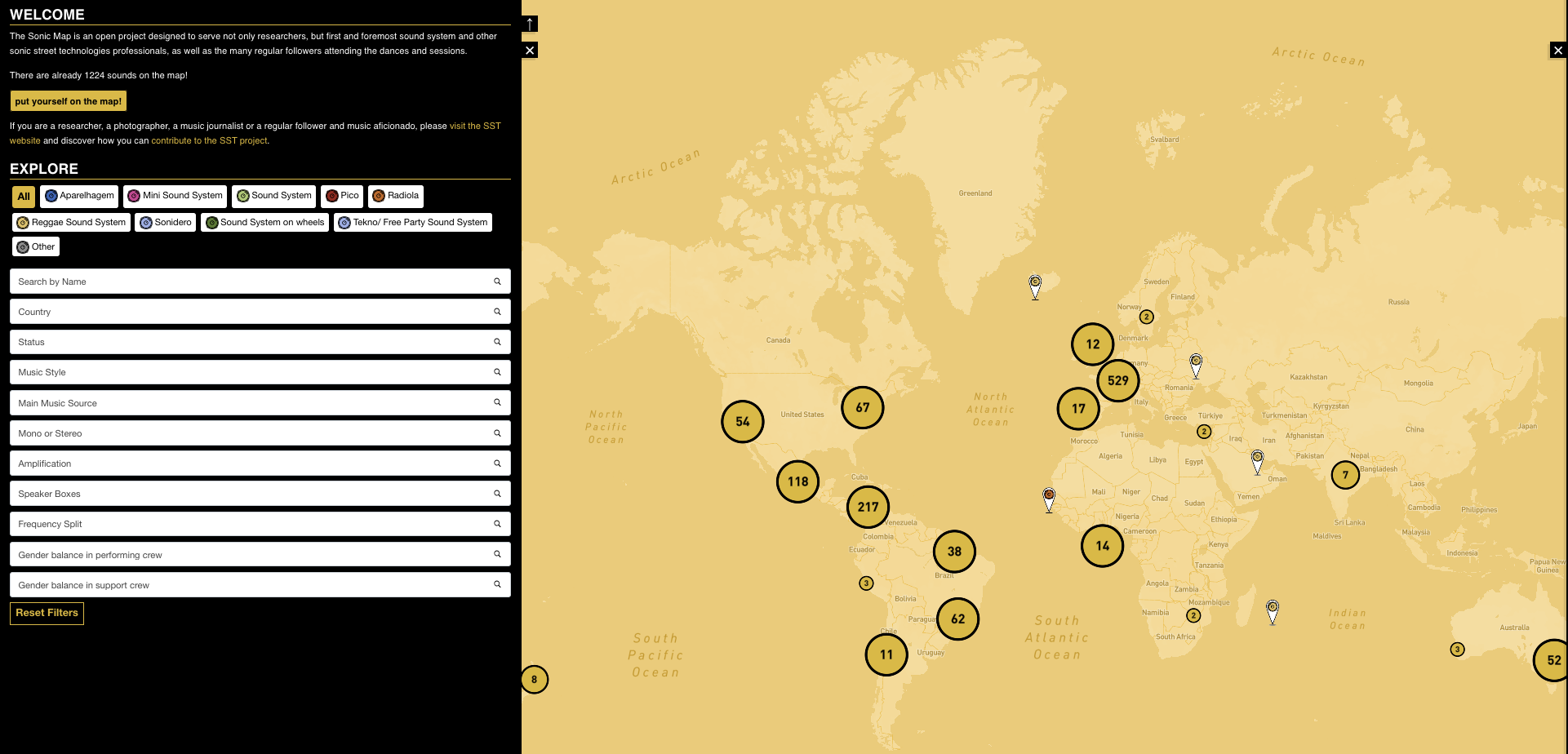

One of the project’s major achievements has been to map the extent of the different sound system cultures currently active around the world. The qualitative analysis of case studies and films (see below) has thus been complemented by a quantitative survey, whose results are available on the SST website. The Sonic Map currently includes over 1,250 sonic street technology profiles across all continents, with new submissions still coming in at the time of writing this blog. Each sound system profile appearing on the map is linked to a database entry where the sound system owners have shared substantial information about their technology, history, music tastes, and crew demographics. This makes the Sonic Map the most ambitious mapping operation of its kind to date. In addition, some but not all the data is published and publicly available as the SST Sonic Map, thus making a significant contribution to the project’s commitment to sharing findings with participants and researchers alike.

Sonic Map

The Sonic Map has been one of the most challenging aspects of the project. The voluntary contributions of sound system owners could not be taken for granted. Instead, it relied on a meticulous job of online and face to face networking conducted both on a local and global scale. About a third of the questionnaires have been uploaded spontaneously, thanks to the project’s strong social media presence (facilitated by Italy-based Astarbene media team) and specific interventions on the field. Other questionnaires have been sourced by specifically trained Research Assistants with local knowledge and an established profile on the scene, including community organizers and former practitioners.

SST Sonic Map, screengrab

As expected, the Sonic Map has not achieved full coverage of the global sonic street technologies culture, which is exceptionally vast, fast-changing, and often exists, either voluntarily or de facto, completely off the radar. In fact, full coverage was never the aim; rather, the goal was to capture a snapshot with analytical depth of specific areas of interest. More important than the numbers, the Sonic Map has given the project deep insight into different scenes, allowing us to engage with the complexities of mapping subcultural formations and to address issues related to data extraction and cultural representation. In a somewhat paradoxical way, the project has gained as much knowledge from inaccessible areas, distrust, or outright refusals as from successfully mapped countries, showing how diverse approaches reflect shifting social conditions, post-colonial legacies, and the place of sonic street technologies within the broader local cultural landscape.

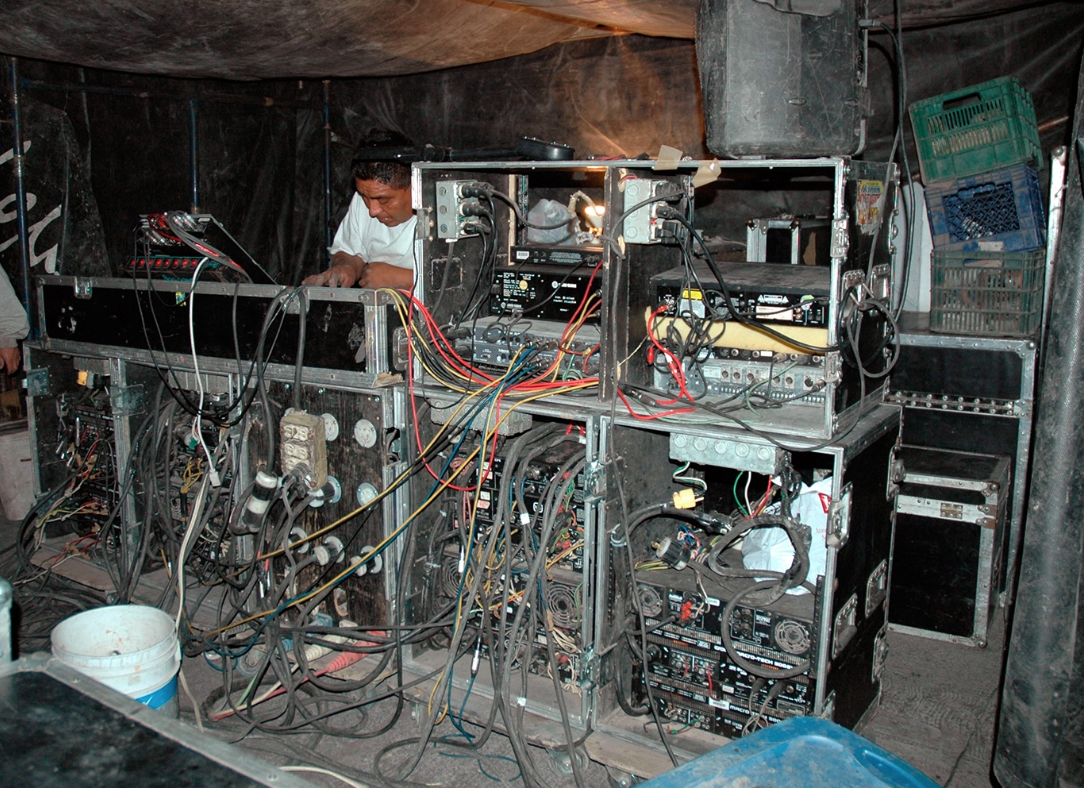

Electromagnetic Diaspora

Overall, the research reveals how street technological equipment, broadly speaking, is shared across different sound system scenes around the world in what are calling in the Mobile Music Machines introduction an electromagnetic diaspora. But just as these scenes play different genres of music in Jamaica, Colombia, or Brazil, so too do their equipment and configurations vary. For example, the technological differences between a Colombian picò and a Brazilian aparelhagem reflect distinctions in environmental conditions, music legacies, business trajectories, and sonic signatures. This has allowed us to trace how the technology-culture relationship is embodied in practice. The research revealed a fascinating variety of technological attitudes, even within the same scene: from sonideros’ DIY re-engineering of record decks to produce the slow-tempo cumbia rebajada, to female Mexican sonideras in California, who eschew ownership of speaker boxes and electronics altogether in favour of the voice as their technology.

A Mexican sonidero

Films and Screenings

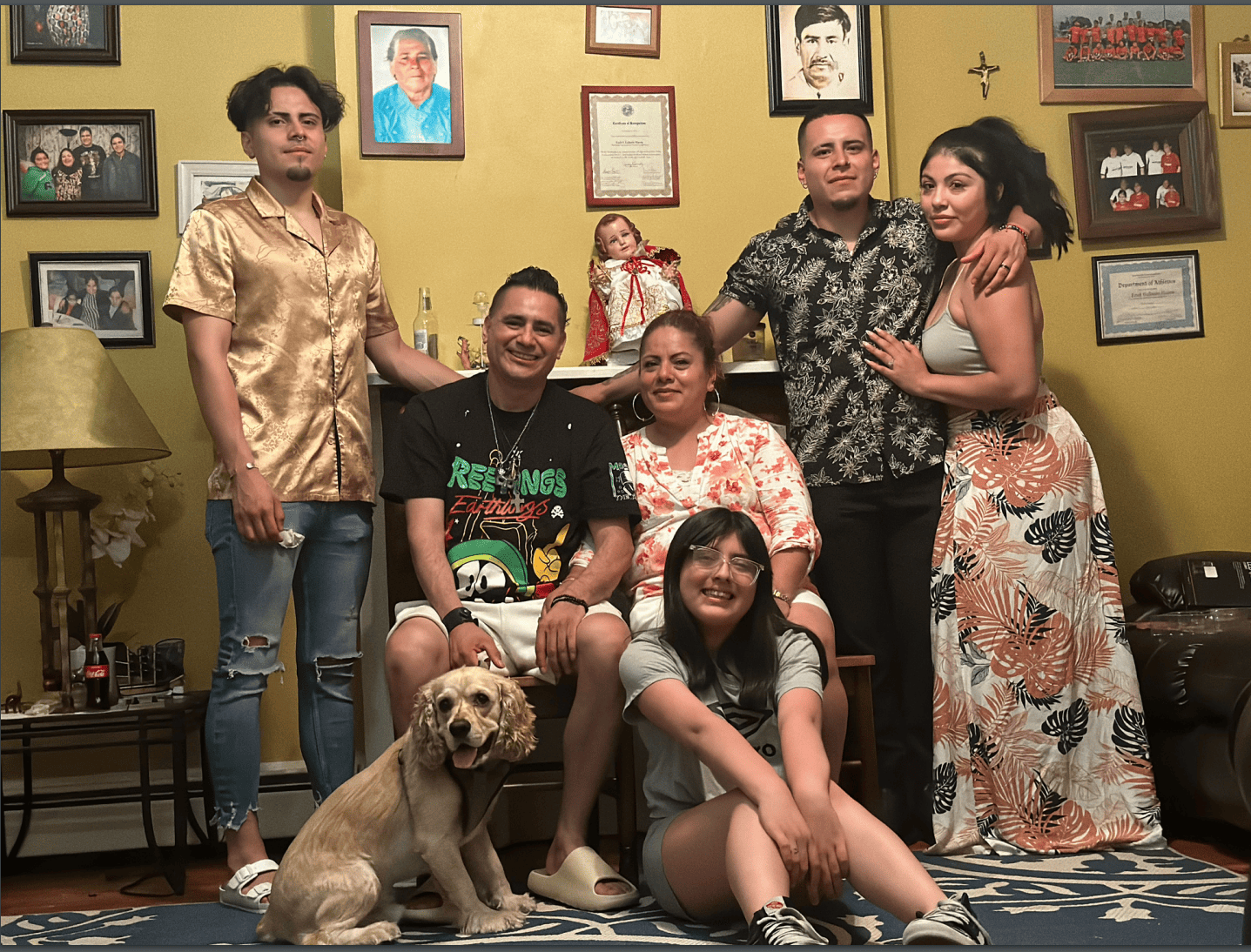

An unanticipated outcome of the project has been the central role of our documentary films in the research process. The project produced six longer films—Rockers Sound Station, Generation 2 Generation, Sounds of the Future, Cesar Rebolledo González’ The Sound of Dreams), Musas Sonideras USA, and Ricardo Vega’s Playing with Purpose— and commissioned nine more shorter ones, which also showcase the filmmaking talent present within the music scenes themselves. The longer films were crucial in collecting interviews and capturing the experiences of participants to specific case studies, providing rich, in-depth material that directly informed the research and generated further community engagement. Meanwhile, the full set of filmed interviews is being compiled into a publicly accessible archive on the SST Video Archive YouTube channel, where it will be gradually updated throughout 2026. All of the films will eventually be uploaded to the video archive, though not before they have had their life in festivals and special screenings.

Ray and family, from ‘The Sound of Dreams’, dir. Cesar Rebolledo González

All this screening material has already proved itself a very effective way of sharing our research results. This has been with both other researchers and between music scenes, so far at conferences in Mexico, Jamaica and the UK, community events in Colombia and Italy and most recently in Dijon, France. Furthermore, in the hands of the practitioners themselves (who have joint copyright) the films add value as collateral for leverage with their local police and authorities, as with Uraba sound system, or to nurture discussion in occasion of international tours, as with El Gran Latido’s recent EU appearances. The project was founded on a practice-as-research methodology, but we also found practitioners-as-researchers (Edgar Benitez aka Dr Tiger from Bogota, Colombia; Dr Moses Iten aka Cumbia Cosmonauts, Australia) and even practitioners-as-filmmakers (Ricardo Vega from from El Gran Latido, Colombia). Research is for nothing if it doesn’t bring surprises.

If the films provide cultural capital for the sound systems themselves, the project’s own cultural capital—through our ERC funding—further supported the sound systems by opening doors with local universities and authorities. For our SST team colleagues in Global South universities, the international status of the project has been empowering, giving new visibility to previously dormant research interests and providing leverage for their own local research funding applications—several of which have already been successful.

SST Global Team

Finally, a major achievement has been showing how effective a research operation that was both global – in terms of geographical scope – and local – in terms of the details of a particular music scene. But such local research would be impossible without the energy, enthusiasm and expertise of local researchers and practitioners. Also, not to forget our university directors of research, Professors Josh Kun (University of Southern California, Douglas Kahn (University of Sydney) and Paul Heritage (PPP, Brazil). This brings us to a final point. Perhaps what the project can be most proud of is bringing together the global SST team. This has enabled us to be preparing the four volumes of research findings but also has established a network for further research – both with us and between each other. This is a further unanticipated benefit of the SST project.

Conventionally, it is only after the official end of a research project like this, that its impact and legacy can be secured – in the writing-up and publishing of the results. With SST it is a bit different, given that we have been blog-publishing from the start, maintaining the Sonic Map and that our ongoing film screenings and that the research process itself, such as practice-as-research events, have had a positive impact on the music scenes involved. Nevertheless, the more formal academic outputs of the Mobile Music Machines series are critical for the legacy of the SST project. It is this, along with the website and map – live and online until 2035 – that will help to resource and encourage further the all-important research in the subject area of popular music street technologies.

We look forward to continuing to keep in close touch with each of the SST Global team members as they write up their book chapters. The four volumes of Mobile Music Machines reflect exactly the geographical organisation of the SSO#11 panels: The Jamaican Sound System Diaspora (Jamaica, Canada, UK); Global Resonances (Australia, India, France); Music Machines of Mexico, Colombia and USA (edited with Cesar Rebolledo); and Sounds of Brazil (edited with Leo Vidigal and Marcus Ramusyo Brasil). So, we have editorial meetings ahead. The blog will also remain open to guest contributions and occasional blogs from the SST extended team – do get in touch in you feel like!