Sketching and Skanking

by Julian Henriques

“For me Shaka was doing something different to the other DJ’s: his dancing and creative performance throughout the night. I was drawn to Shaka’s sound because of his individuality and that he didn’t isolate himself from his audience, always performing on the same floor level, as a part of the crowd. He united people through sound. His deep hypnotic, ancestral presence making us all feel purified, strong, and free of the complicated network we live in. “

Denzil Forrester

We start with a few words of appreciation for the great Jah Shaka. The Grenadian/ British artist Denzil Forrester is one of the multitude whose life and work has been inspired by Shaka, as he explains in what follows.

Jah Shaka was a unique sound system. His performances showed some of the extraordinary capabilities sonic street technologies can have. One is their sheer inventiveness to transform streets, markets or car parks into sites for intense shared vibrational sessions. Another is their abilities to spread the vibes of the dancehall – just as do sound waves – far and wide in every direction. Reggae is known as a global music with festivals around the world. What is perhaps less know is the way in which the dancehall aesthetic at the centre of the Jamaican popular culture is inspiring several fine artists – crossing the boundary from street to gallery.

With his paintings Denzil Forrester makes a bridge between the predominantly sonic and live kinetic world of the dancehall session and the flat static dimensions of paper or canvass of the gallery show. Forrester has been working over several decades sketching in London’s dancehalls – Jah Shaka’s in particular – and has developed his own language for crossing this boundary. For Forrester this is not a matter of trying to translate one medium into another. Instead, he is in the business of expressing the feeling, substance and movement of his dancehall subjects – rather than trying to describe in charcoal or oils how they might look to the eye. Often there is not a lot to see in the darkness of the dancehall; but there’s certainly a lot to feel. Thus, Forrester generates his own dancehall world on sketchpad and canvass.

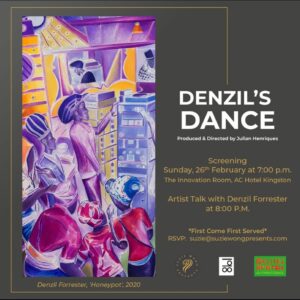

What follows are extracts from some answers Forrester gave to audience questions following the premier screening of my documentary, Denzil’s Dance, at the AC Hotel, Kingston on 27th February this year. The film features Forrester sketching in several dancehall sessions on his first ever visit to Jamaica in 2019.

Figure 1 Flyer for Kingston screening and audience

How do you make use of your dancehall sketches for your paintings?

DF: I’m using them to make another drawing so I know where things are going well and trying not to get it too static because the worst thing you can do to these very energetic dynamic drawings, you don’t want to touch them after if possible. It’s best to leave them, but use them for putting the painting together. Because you’re trying to create, not trying to recreate, but when you were there, and that’s the thing about going to these spaces, that energy and feeling that was there, that might be in the drawing, but it has to be within your own energies as well. That was the exciting thing about attending these functions. It’s a lot you remember in your body.

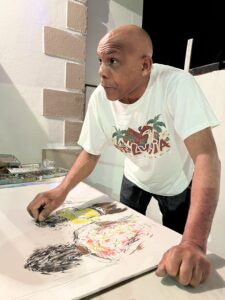

Forrester sketching

When you come to making the painting, you can splash out now and then, and if it goes wrong, you just have to wipe it down and start again, but all that stuff comes back within you. That’s the important thing about going and doing it because it’s not only the drawing, but there is something inside of you that’s remembered, you muscles, all that stuff inside of you.

How do you choose who to draw?

DF: When I was drawing in London with Jah Shaka, there was a crew, about five or six people that always helped Jah Shaka. Those people, I must have drawn them about 30 or 40 times, literally because they’re always near the DJ. They might be toasting sometime, rapping. I got to know them a lot because I’ve used them in lots of different paintings. The interesting thing was with the Jah Shaka thing, having drawn Jah Shaka for about 20 years, and just before lockdown when I came from Kingston, I went back to London, and Jah Shaka was playing in, I think, Ladbroke Grove. I went there after having drawn Jah Shaka for about 25 years. The same group of people that I’ve drawn like, I don’t know, 50 or 60 times, they were all there, 30 years older, [laughs] in the same very similar position.

Some people come and stand close to you. They’re not saying, “Draw me,” but they’re standing close to you, so you have to adopt a different energy. That’s a beautiful thing about gesture. You’ve got to adapt to the different clubs you go to. Like in London, the club I used to go to is called Phoebe’s. The top part was a disco so, mainly R&B music and some lover’s rock reggae, a London-based music. It was very quiet and gentle and people just look, and then the heavy dub comes at one o’clock in the morning, Jah Shaka, and it’s totally different again. You have to adapt. That’s the beauty about drawing. You’re using different energies according to the different spaces that you’re in.

Forrester sketching at Uptown Mondayz

[On my trip here to Jamaica in 2019] there was a guy in the Kingston Dub Club. He was all in white, awful white. He started, it was like an orchestra. There’s always someone in the crowd that is going to wake them up. It’s happening now all the time. Someone just comes out and do something, really wild movements, and next thing, the whole thing has come alive. The Dub Club, I got some lovely drawings and energy just because of this one person, this guy in a huge [dread] locks. He wasn’t featured a lot in the film. Whereas, you’re right, there’s more static. If you look, there’s a woman I draw.

That’s why I’m saying you have to be there and absorb that energy and just be true to it because if someone is not doing lots of energetic movement, I wouldn’t been doing lots of energetic movement on my paper. Because we went to this ’90s club last night and the generation is basically in the ’40s and ‘the ’50s and they were very static. They were very quiet. [laughter] That’s the exciting thing about life and that’s the exciting things about Kingston and all these different clubs where you got all these different groups.

Showing his work to one of his subjects

We see you drawing with two hands, do you have to practice that?

DF: No. It’s only happened accidentally. It wasn’t a deliberate thing. I don’t realize why. I actually consciously realize why, but I just started doing it because we use two hands to do lots of things. Plus, when you dance, you don’t just dance with half of your body or one bit of your body. That’s the thing. When you’re trying to draw someone, you’re trying to move with them. Both hands make it much more easier to feel the whole thing. It makes you move around faster, quicker, the gesture because you don’t want to start thinking about it. It happens in seconds.

The best thing is not to stop as well when you’re doing it. You might slow it down, you might speed up, but you don’t want to stop because then you might start thinking about it and you don’t want that to happen.

Could you ever make your work without going to the dancehalls?

DF: The important thing about going to this nightclub yourself because the drawing is evidence that you have been there and make this, but that energy is retained within your physical vein. If you are drawing when they’re doing lots of movement, you got to do lots of distortion to break it up because sometimes I will try and echo the sound, the beat, but that has to work for the whole thing. You can’t just do a broken-up beat of one section of the painting. It has to be throughout. Sometimes I’ll focus more on the figures being static.

Dub Strobe 1, 1990, Oil on canvas, 213.8 x 152cm

For instance, there is one column, Dub Strobe, where I use a lot of the strobe lighting to distort the figures, but what that helps me to do as well is to echo the sound, the movement as it travels through the spaces. The main thing that attracted me to go into these spaces was the music. When you’re doing it, you have to watch out. That’s why the gesture drawings are good if you’re being true to it because you’ll not only be drawing this energy of a person, people moving out, but you’ll be trying to get the sound as well. You don’t have to think about it because if you’re giving yourself over to it and doing it, it will happen because you’re there for all those things.

Not only the people, but the sound, the atmosphere in the room. There is a drawing I call Cave, an early one I did call Cave, where the bodies echo in the rhythm a lot where it distorted the light. Yes, so it depends on the sound. The sound will help you to break it out.

Your paintings are full of colour, but the dancehalls themselves have little or no light, please explain?

DF: A lot of the early spaces that I did in London, it was so dark. Basically, I use color quite spontaneously. Like I said, I was born in Grenada and I think emotionally. We all have our own sense of color when we paint, and it’s very difficult to teach someone about what color they should use and whatever because I think it’s an emotional spontaneous. Me and my partner, Phillipa, we’ve been together for about 50 years, and our pallet is very different, but there is similarities.

Carnival Dub, 1984, Oil on canvas, Diptych, overall: 336.8 x 398.7cm

I think because I was born in a hot climate, because I heard a fellowship in Rome for two years in ’83 to ’85, and there’s a painting called Carnival Dub I did, which was a very bright orangey yellow painting because I wanted to bring back the spirit of carnival in the painting. Being in Italy I think helped me a lot to bring that color feeling inside of me because in London, the paintings were bright, but your trouble is, if you live in a space like London, there is a dark graininess to it. You’re still using color, but it’s much heavier, it’s much more weighty. Whereas in Italy, the whole thing became more playful and lighter because you got to give yourself open to where you are.

It’s like, say, if I was to make painted in Kingston, well, I wonder what the colors would be like because it’s so bright and lighter. I’m in Cornwall now. Cornwall, there’s not a lot of pollution there, and there’s lots of purpley, violety, but very light colors and stuff. I don’t worry too much about when I paint. I don’t think too much about the color. It happens very spontaneously, but I tend to use a lot of blues and purples and stuff like that, which is, again, is emotional, but you get a lot of that in the nightclubs with the lights and stuff like that.

How do the drawings you make in the dancehall relate to the paintings you make afterwards?

DF: Yes. What you’re saying about the disappearing, I think the drawing have that kind of element of the disappearing because they’re not quite finished. I think that’s why they’re so unique, I think, if you do that type of drawing in that space. You’re capturing little snippets, but all those empty spaces are very important. Whereas I think the painting, because of, I suppose, the way we make paintings, I suppose you are after another energy in the painting. This is why it’s so important for us to make drawings. I sometimes think the drawings are more exciting to look at than the paintings because they’re talking about what you are talking about.

The bits that are there, but you can still feel. I never used to throw the drawings away, the ones I didn’t like, I always keep them. The ones that didn’t see anything in them, after about 30 or 40 years, I started seeing things in them. That’s so exciting because things are coming back probably that you realize wasn’t there. The drawings are so exciting I think because they capture what you were talking about.

Dancefloor, Uptown Mondayz

Question for Julian, why did you want to make this film with Denzil?

JH: Literally, I enjoy it. To be able to work with this amazing artist, and so taking some of the ideas that I have about how sound works and how it affects our bodies, and how we live in this amazing world that we sometimes just don’t recognize. I feel energized at another level from Denzil’s work. Just for someone to be able to show what can become of this street energy. Giving it back, yes, of course, but just taking it to such a level of refinement and subtlety, it’s just beautiful. I feel privileged and energized by being able to work with Denzil.

Denzil Forrester current exhibition:

https://icamiami.org/exhibition/denzil-forrester/ ICA Miami 6th April to 24th September 2023

–

Julian Henriques has been researching, publishing and making films with and about sound systems in Jamaica and the UK for many years. He is a Professor at Goldsmiths, University of London.