Urabá Sound System: Playing with Purpose

Today’s photo essay is the first in a series of guest-authored blogs. Colombian photographer Manuela Uribe and Ricardo Vega of El Gran Latido sound system introduce us to the colourful world of picos from Urabá. Through the beautiful stills taken at the first Encuentro Picotero, held in Urabá in July 2021, they tell the story of how pico culture can help community weaving in a region historically plagued by gang violence and state neglect.

This blog is also available in Spanish at this link.

All images © Manuela Uribe

—

“Urabá Sound System: Playing with Purpose” has been an “encuentro picotero” (a picós meeting), held from July the 2nd to July the 4th, 2021 in the Municipality of Apartadó, in Urabá Antioqueño – Colombia. The event included musical and cultural sessions, such as discussions on the context, history and challenges of the picó culture, and a “memory carousel” where photographs, vinyl records and memories were shared. The participants also collectively produced a written aiming to demonstrate the relevance and effectiveness of the picó sonic practice as a scenario for peace building. On the last day, the event hosted a “picotódromo” (music session with different picós) which saw the participation of 8 picós from Apartadó. This seminal event was made possible by the work and support of The Truth Commission, the Apartado Institute of Culture, the “Mi Sangre” Foundation, the Gran Latido Sound System and Fundasevida.

Apartadó is a Colombian municipality located in the department of Antioquia, in the Urabá region. Apartadó means “Plantain River” (“Río de Plátano”) in the dialect of the Katía indigenous language. Apartadó is the largest banana zone in Colombia. It counts more than 180,000 inhabitants – a rich and diverse cultural mix that brings together Afro-descendants, whites, mulattos and indigenous people.

Apartadó has been historically plagued by devastating violence caused by the internal armed conflict, as well as drug trafficking and the dispute over land and territories. Today, Apartadó survives in the face of complex political, economic and social conditions.

The Chinita massacre took place on January 23rd, 1994. That day, the now-demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) broke into a verbena (a picó session) murdering 35 people – including men, women, children and elderly people. The FARC guerrilla alleged that members of another opponent guerrilla organization (EPL) were there.

The verbena was being celebrated in La Chinita neighborhood, a working-class area mainly populated by banana companies workers, unemployed or landless people. The verbena had been organized with the intention of raising funds to support the enlargement of a community school.

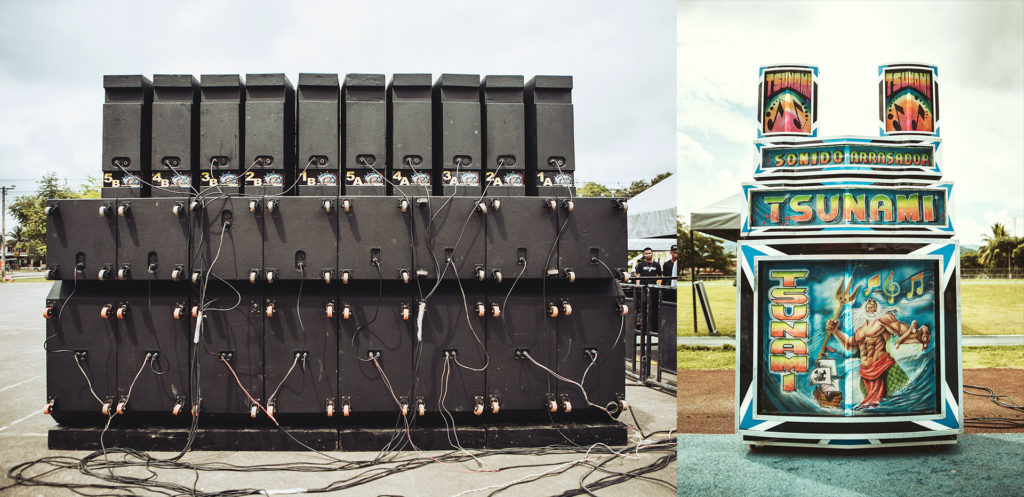

Picós are colorful and powerful handmade sound systems from the Colombian north coast. They are relatives of Jamaican sound systems. People began building picós during the 1950s to listen to African music vinyls that were imported to Colombia by immigrants, sailors or seasonal workers, mainly travelling by boat.

The picó (el picó) is a tradition that has been passed down through generations – usually from father to son – for more than sixty years. Picós are essential for the well-being of the community. They foster and create scenarios where the identity of several communities is built and projected.

The degradation of the Colombian armed conflict, together with the class prejudice and the structural racism, have turned picó into a precarious, outlawed and persecuted cultural practice in Urabá. Picós sessions provide one of the few spaces for the community to freely gather. Unfortunately, this openness also turns a pico session into an ideal scenario for conflicts derived from state neglect and neoliberal economic dynamics to detonate in full force – such as gang conflicts or paramilitary control.

Since December 2017, a decree banning the traditional picós dances has come into force in several cities and townships in Urabá. The measures were justified by the need to generate a better perception of security in the population, due to the high rate of gang violence. Picós have continued to play in nearby villages, mainly in private or paying events which are therefore not totally accessible to the entire community.

“Urabá Sound System: Sounding With Purpose” was designed as an encuentro picotero (meeting of picós). It was launched with the aim of claiming this culture as a tool for healing, memory and resistance in the face of the ongoing vicious armed conflict. It is the result of a process that began in Bogotá with El Gran Latido Sound System outlining the legal and pedagogical tools for the protection of this practice. This has initiated a process of re-evaluation of the picó as a relevant cultural force.

Since the event “Urabá Sound System: Sounding With Purpose” took place, picós have started to play again in the urban centers of the municipalities of Turbo and Apartadó. They have done so to reclaim those spaces as communal spaces, as well as to raise awareness on the importance of creating an agenda of social work and community support, created and managed by the picós themselves.

In the aftermath of the event, no acts of violence have taken place at picós dances in Urabá .

Colombian picós traditionally play African music. But throughout the years – and thanks to the connection with other music industries and genres – the music culture that feeds the picós dances has been widening. Nowadays rhythms such as champeta, salsa, vallenato and also reggae have come to coexist within the picó musical world.

Unlike the Northern Colombia area (Cartagena, Barranquilla and Santa Marta), and due to its proximity to Panama and Jamaica, in Urabá the musica picotera or picó music is strongly influenced by Panama’s la plena and by the 1980s and 1990s reggae and dancehall rhythms. This phenomenon continues today, as testified by the popularity among the pico crowd of locally-made remixes and Spanish speaking adaptations of Jamaican songs, which are among the most celebrated “exclusive tunes” played by the picós in Urabá.

As a sonic street technology, picós have evolved over time just like Jamaican sound systems. They originally relied on valve amplification. Later, they began to assemble the so-called turbos, in which most of the speakers are packed in a huge, single box, beautifully hand-painted, like Tsunami (see previous picture). Currently, the new generation of picós are quite similar to reggae sound systems in terms of the technology they employ. But they continue to be identified and differentiated by their colourful Caribbean aesthetics. Most of the speakers are handcrafted, although many use Cerwin Vega bass boxes.

The cultura picotera (picó culture) is deeply anchored in the memory of Urabá and its people. For more than thirty years it has provided a meeting space and a tool for the construction of the social fabric. The lived experiences of the Urabá people are in many cases projected into these spaces of dance, conviviality, union and enjoyment. A picó session is a special event for the community. Facilitating the meeting with each other, the encounter of identities and bodies “in action”, the picó culture is an instrument of community weaving.

Dancing is a vehicle of expression for human beings. It is capable of mobilizing and generating vital scenarios for imagination, face-to-face interaction, the creation of identities and the re-appropriation of space by the body.

When dancing – that accumulation of gestures in movement – our creative bodies embody different roles, dictated by the needs of each community, and we become promoters of change, mutual acknowledgement and respect for ritual and ancestral knowledge.

Dance as a catalyst for well-being resonates in the scenarios of peaceful resistance, through the minds and hearts willing to connect, to heal, and to understand that the respect for life is a sacred and fertile land that makes everything possible.

Urabá is plagued by decades of violence, pervasive state neglect and generalized dereliction. The population is not offered fair opportunities, neither basic human rights such quality education or an efficient health system. In this context, the re-signification of cultural spaces that belong to the community can help to rebuild the wounded social fabric.

It is about planting the seeds of change through the exercise of peaceful coexistence and enjoyment. This allows for new mental and emotional connections around which these experiences re-connect ourselves with the most sacred values: those that honour life, difference, and collective work. And also those that promote individual contributions to a network that will ultimately benefit the whole community.

Change is necessary and vital, as well as the understanding that it is not only emanating from those in a position of power; it can also be activated by the re-tuning of our hearts.

During the picotero meeting in Urabá, people of different ages gathered. They were summoned by the desire to share personal memories and feelings. They gathered because of the love for the music, the need for spaces of conviviality, creative expression and union. That created the ideal setting for the encounter with others. This inter-generational and inter-cultural mix amplifies social cohesion. It also makes evident the significance of spaces that take families outside the framework of their private life. It offers them the opportunity to extend their own way of inhabiting space out of those that usually belong to them. Ultimately, it resignifies the public space as a place of meeting and communion.

In order to rethink the communal spaces such as those where picos play, it seems essential to go back to – and to remember- its traditional essence, its original knowledge, and to reconnect people with its history and meaning. From this perspective, it will be possible to put into context the important role played by picós within the communities. We can ultimately understand the value of tradition as long as it continues to respect its original spirit, and to benefit the people and to sustain their development.

—

Manuela Uribe is a Colombian photographer, lover of music and people, currently living between Buenos Aires and Bogotá.

Ricardo Vega is the founder of El Gran Latido sound system, based in Bogotà, Colombia. He is a promoter of reggae and sound system culture in Colombia and in South America at large.