SST COLOMBIA RESOURCES: AN APPROACH TO THE STATE OF THE ART PT.2

This week’s blog continues the exploration of the Colombia SST Resources now available on our website. After having presented us with the main topics and streams of existing research on Colombian picós and sound systems (see previous blog), bibliography curators JJ Carbonell and Edgar Benitez provides us with a very useful commentary on the features, issues and opportunities that their work has unveiled with regards to the state of the art of Colombia SST Research.

by Juan José Carbonell and Edgar H. Benítez Fuentes

Written resources: a commentary

An important part of the revised bibliography is the result of research funded by universities or national institutions. Others are monographs or dissertations from different fields of study, sometimes from field research. Some of these include quotes from interviews with practitioners from the picó or the champeta scene. Some documents are articles in non-specialized magazines with regional circulation, blogs or web pages dedicated to cultural management or music promotion for the Colombian Caribbean and Colombia in general. Most of these documents’ focus is on champeta music and its sociocultural context, and the picó is included due to its closeness to the main subjects.

History, economics, socio-cultural context, race, class and marginalization are the most recurring topics in the documentation, reflecting how both champeta music and the picó have developed in marginalized neighborhoods of cities such as Cartagena, Barranquilla and Santa Marta, with a smaller presence in towns and villages throughout the region.

- It is necessary that the documents present the data and texts of the investigations in a scientific manner, avoiding exaggerations.

- More critical debate would benefit the development of the research around the picós.

- It is urgent to implement public cultural policies that fund, finance or support research around the picó, open to both researchers and cultural actors from within the scene.

- Lack of academic spaces such as conferences, seminars and symposia dedicated to research around picó culture must be addressed.

- Secrecy in the picotero/ champeta scene. This represents an obstacle to the investigation since much of the information of the picotera scene has been kept secret and can be difficult for investigators to access. It is advisable to cross-check the acquired data, in order not to fall into inaccuracies or misunderstandings.

In recent years, the fields of musicology and ethnomusicology have gained force in Colombia, as reflected in an significant segment of works (some of which have been included in this bibliography). These have contributed to a much more rigorous treatment of the subject, guided by a more scientific approach. One of the most innovative elements that this literary production adds to the existing debate are the testimonies of artists, DJs, MCs, technicians, and protagonists of the picotera/ champetúa history who begin to be given voice in the investigations in a more systematic way.

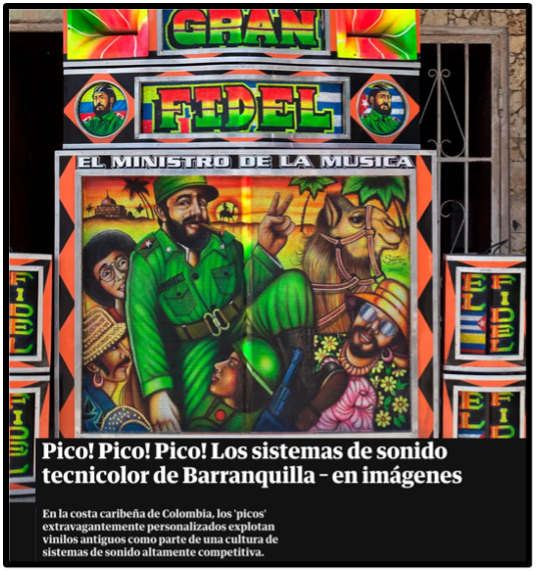

Barranquilla picós featured on The Guardian

Opportunities:

From this overview, we can identify several lines of research. The first one builds on the secrecy or disinformation that originates in the anonymity of the exclusivos, the unique and rather mysterious records that made a picó’s reputation. Researchers could be in the position of revealing the true origins of these legendary songs, whose titles and authors have been hidden for fifty or sixty years. Very few of the texts reviewed engage with this topic in depth. Further research can include the techniques that picoteros and DJs have developed to select tunes; the logistics and import strategies, or the safety procedures that allowed these tunes to remain anonymous for so long. We are at a key historical moment to develop these lines of research, since many of the merchants and vendors who imported this music are still alive.

The second line of research that this review opens up is a critique of the existing scientific literature. This could be carried out from within the academy, by research peers who can amend or confirm the information already presented; as well as it could be approached from the exercise of the daily work of the practitioners, singers, musicians, picoteros, DJs, producers, engineers, technical and logistical personnel involved in the picó and champeta circuit.

The third and broadest line of research, cutting across different fields, is related to the technical and technological evolution of the picós. In the field of sound engineering, it is necessary to study the different formats of speakers, amplifiers, preamplifiers, and all those information and anecdotical knowledge that only builders can provide to researchers. It must be noted that turbos, fraccionados and juniors are usually locally built, even though they can sometimes make use of off-the-shelf or imported components. So, both industrial design and carpentry open lines of research in terms of the different formats, components and designs that are manufactured, or hand built, as well as the finishings. Finally, with regards to plastic and graphic arts, it is possible to research the techniques, as well as the tools and supplies used, for both handmade paintings and digital designs.

There is a fourth line of research referring to the picós as a recording industry. It would be interesting to investigate the shift from playing music to making music, including the recording of songs from production and postproduction to music release, manufacturing and distribution. It would be particularly interesting to explore actual data related to production, sales, reach out, and so on. (Gualdrón 2015).

Book by JJ Carbonell, 2022

Grey Bibliography: A Commentary

Within the the grey bibliography, we can identify three types of sources:

- Filmography, which maintains professional production standards.

- Blogs, mostly created to collect and share (usually in a very reliable way) information already available across existing archives.

- Online content, created by influencers of the picotero and champetúo scene.

We can attempt a first classification of this grey bibliography according to its scope, impact and audience:

- Specialized audience: this group includes blogs and filmography that have very few users and barely reach dozens or hundreds of views.

- Mass audience: influencers and social media channels that reach hundreds thousands or millions of views.

These channels can be further divided according to the time taken to produce the information:

- Hectic: those constantly producing content, the so-called immediatistas. These channels seek popularity, which leaves them short time to elaborate the information.

- Sporadic: those producing less content. These channels tend to work without pressure so they can collate and compare information in a more reliable way.

Although they are not media entities and do not employ professional journalists, it is possible to classify online sources based on the type of information they provide:

- Sensationalist or conflictive: those channels creating tendentious content or fostering controversies in order to go viral.

- Educational: those presenting more informed content based on verified information.ì

They can also be classified according to the type of source they rely on:

- Single source: those that produce audiovisual content based on a single article or video. Their information is usually not verified.

- Individual interviews: where information can be contradicted or verified.

- Group interviews: these cross-check information from different testimonies.

- Multiple sources: where information is sourced from testimonies, data and/ or existing resources, and isusually cross-checked.

The sources themselves can also be classified in:

- Existing written or grey bibliography

- Testimonies from picó practitioners and professionals (sound engineers, picoteros, pianists/samplistas, MCs, singers, musicians, producers, and others).

- Researchers, journalists and information professionals.

- Influencers.

The main issue related to social media content is that the most popular sources are usually those that spend less time in cross-checking their information. This content usually relies on a single source that is not verified, and it is often tailored for visibility rather than reliability, i.e. with influencers interviewing other influencers. Popular social media channels or influencers usually produce sensationalist or conflictive content. However, there are also social media channels offering interviews, sometimes with innovative formats, with the protagonists of the picotero movement.

Opportunities:

Online sources allow journalists, social and audiovisual communicators, as well as singers, musicians and other professionals, to contribute to increasing knowledge and information about picoteros and their sonic practice. Some of these content creators are already part of the music industry, such as DJ Dever and Nando Black. Just as social media open the possibility of sharing testimonies from creators and aficionados of the picotero circuit, they also provide a fertile ground ground for the creation of high-quality transmedia pieces, which could retrieve the lines of research already explored in the written sources, since most of them has had limited online circulation.

Well known social media channel directed by Jose Davido

Colombia SST Resources: Conclusions

Finally, with reference to the the difficulties that this bibliographic exercise has faced, the following can be noted:

- Further research conducted by university students could be added, but this has been of difficult access.

- There is the need for further research on the actual sound technologies and the role they play in the local communities that aproppriate them. In this sense, several lines of research may arise.

- On a global level, rigorous analysis and comparison is needed between the sound systems used in different parts of Latin America and in the Caribbean, a task that, incidentally, is included within the objectives of the SST project.

- An intergenerational meeting between the audio engineers from the 1980s and 1990s picó scene (mostly valve-based) and the current generation of technicians could reveal the importance of the different technical configurations and facilitate technical progress within the scene.

- It is necessary to expand the research on sound systems and picós to regions such as the islands of San Andrés and Providencia, other regions of the Colombian Caribbean, towns and cities such as Bogotá and others where sound systems are likely to be locally present and active but lack a wider exposure.

- It is necessary to reserch the different profiles (DJs, samplers, technicians, artists, fans, among others) that contribute to build and put into practice the technical knowledge within the picó ecosystem.

Authors

JJ Carbonell is a musician and cultural manager from Cartagena, with a degree in Journalism from the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. He is the author of the Champeta. Resistencia Cultural en el Caribe (2022).

Edgar Benítez aka Dr. Tiger is a musician and DJ, anthropologist from the National University of Colombia and currently a Bogotà resident.