Colombia Fieldnotes pt.2

This is the second blog reporting on the early stage of the ongoing SST research in Colombia (read the first one here). Here the focus is on the music – as it is for practitioners, professionals, and aficionados who gravitate in and around picotero culture. The shared passion for the music can prompt change in performance styles and technological trends. It can also fuel long-running disputes and competitions between cities or across generations. Music is therefore relevant to the SST research especially due to its interrelation with technology. While the latter firmly remains the project’s main interest, it must always be considered as part of the wider cultural, social and musical ecosystem that makes up a sonic street technology scene.

by Brian D’Aquino

Discovering champeta

Champeta is an indigenous music genre strongly associated with picó culture and parties and characterized by a rhythmic prominence that invites bodies to dance. Its musical roots span from West Africa to the Greater Caribbean. Some also associate it to chalusonga, a genre championed in San Basilio de Palenque, a fiercely black enclave on the Caribbean Coast which has been the cradle of Afro-Colombian music, in the 1960s. Champeta’s cradle is Cartagena, also home of the most known Colombian picó El Rey de Rocha, one of the biggest players in the local music industry. This testifies to sonic street technologies’ role in creating, popularizing, and marketing new music genre. They do it through their grassroots infrastructure of street dances and music vendors, as well as by nurturing up and coming artists.

I met Lucas Silva in Bogotá in Deceber 2022. He’s a music producer and filmmaker whose work has been focused on the city of Palenque. His record label Palenque Records has released music from numerous Black Colombian artists as well as Jamaican singers. As a filmmaker, he has co-produced documentaries such as Dancehall a Prueba de Balas (Bulletproof Dancehall, 2018), and the classic Los Reyes Criollos de la Champeta (The Creole Kings of Champeta, 1996). Only later I learned he is the son of Marta Rodriguez, a highly celebrated documentary director and producer whose focus was Colombian working-class culture.

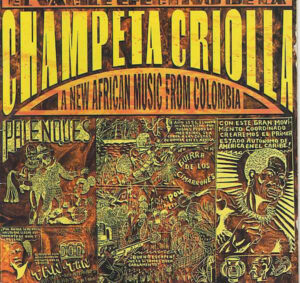

A 1998 champeta LP compilation issued by Palenque Records for the French Market

In our conversations, Lucas highlighted how market pressure, trade rules and financial constraints have contributed to shape music, from the picòs need to play exclusive tunes to attract a bigger crowd to record companies’ involvement in champeta production. Due to my own background as a sound system and record label owner, in my research I am very keen to acknowledge these factors when discussing music evolution and trends. This also to balance widespread Western narratives that sometimes tend to romanticize Global South and Black expressive cultures. As a matter of fact, market pressure does not necessarily exhaust creativity, as it is widely regarded in the Global North. Sometimes it triggers it. And this is especially the case in marginalized environments where generating informal revenues remains a pressing need.

More specifically, Lucas connected the rise of champeta to the popularity of African music (especially soukous, highlife, mbaqanga and juju) in the picó parties circuit during the 1960s and 1970s. Mainly pressed and marketed by French companies, these vinyl records were imported to Colombia by sailors, who created a profitable business by capitalizing on picotero’s need for new and rare tunes, the infamous exclusivos, which could boost one’s reputation and fanbase. The growing popularity of these rhythms eventually attracted Disco Fuentes and other local record companies. After trying to license African recordings for the Colombian market, these companies realized that it was cheaper to re-record them employing local musicians. Inevitably, these copycats added some local flavor to the music by incorporating influences from Caribbean rhythms and Colombian folk sounds that Colombian musicians were trained to play. This process slowly gave birth to what is nowadays called champeta – although the genre’s boundaries and history remain quite blurred.

Shakira’s 2020 Super Bowl performance made champeta trending on TikTok.

Instead, what is indisputable is the stigma associated to the music – literally starting from its own name. The term ‘champeta’ indicates is a type of machete associated to Black, working-class, and poor people from the Colombian Caribbean countryside. Employed with a negative connotation, since the 1980s the term has been used to describe what is in fact an oppressed, marginalized culture. In the same way, ‘champetudo’ (a champeta owner) has been used as a denigratory term, also evoking violence and crime. Interestingly, during its evolution champeta has also sometimes been called ‘terapia’ (therapy). Some claim this was part of a wider marketing strategy through which record companies tried to ‘clean’ the identity of champeta music to appeal to a wider audience.

A champeta knife.

Champeta as a defined genre appears in the early 1990s and it is characterized by digital samplers such as the Casio SK5 keyboard, one of the genre’s trademark instruments. Since then, its influence on contemporary popular culture and music in Colombia has been massive. More than a mere music genre or a dancing style, it truly designates Black Caribbean people’s culture and lifestyle in Colombia.

Exploring Santa Marta

I met Monosoniko Champetuo in Santa Marta in January 2023. A native of Barranquilla, he currently lives between his hometown, Santa Marta and Bogotà. His love for music was nurtured from a very early age. His father owned a small picó domestico. As a child, he used to travel the coast with his family who used to work at festivities and celebrations where picós were the main attraction. Nowadays, he performs as a DJ, selecting a wide spectrum of picó music he calls estilo verbena. He plays vinyl records, also featuring the typical picotero set up (Casio SK5 or SK1 and his own trademark placas). Very generously, he introduced me to the Santa Marta scene by inviting me to an afternoon gig he was playing with some DJ friends .

With about half a million citizens, Santa Marta is the smallest of the three main Colombian Caribbean cities. The comparatively small size of the city is reflected in the features of the local picó scene. In terms of music taste, technology, and culture, Santa Marta can be described as satellite city of Barranquilla, the latter and Cartagena being the two epicenters of the culture. In terms of the local picó population, Monosoniko estimated the presence of about a dozen premiere league picós, some sixty junior, and nearly a hundred small ones. The undisputed elder is El Último Hit, with over sixty years of activity.

Monosoniko digging for tunes. Source: Instagram

In addition, according to Monosoniko, in Santa Marta there’s a few hundred domestic picós, including those playing in private houses, poolrooms, and cafes. But he was quite adamant to point out that, even though they have a pintura (painting) and a name (usually reflecting that of their owner, or the shop they are installed at) they should not be confused with real picós, mainly because they don’t have a programador in charge of the music selection. This proves how the music, its knowledge, and the art of selecting it, remains a defining factor in the picó ecosystem.

We also discussed how the traditional turbo aesthetics is currently trending again, especially in Barranquilla and Santa Marta. This has pushed café owners and shop keepers to shape their in-house sound systems as traditional picós. Monosoniko also mentioned an informal movement of picoteros (so-called Africanistas), playing strictly African music on vinyl and banning any MC intervention, which has helped to re-popularize the traditional format. Sometimes, discrepancies in music taste can take the form of a generational clash, with the older crowd favoring African music without any MCs, versus a younger crowd mainly into the digital sounds of champeta criolla or urbana. Interestingly, in Santa Marta the older crowd was able to secure their portion of the scene due to their spending power: as they can afford to buy drinks more than their younger counterpart, venues and promoters are keen to cater for them.

Poster for a dance at Patio Pescaito, 2022. Source: Facebook

Another interesting, recent trend in Santa Marta is that of the patios. These are the open air courtyards, typical of Spanish colonial architecture. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when the ban on parties was enforced, picós started to play in patios as this made it difficult for the police to understand where the party was.Patio dances continued also after the pandemic, bringing new life into the culture as these spaces were perceived to be safer than the average barrio dance, therefore attracting a more mixed crowd. Some have now become very popular spots for dances, with a few even evolving into official ballrooms charging a small admission fee, such as Patio Pescaito.

Keeping the tradition alive

The current resurgence of the traditional turbo format is not just an elder’s affair. Young people are also into it. Loko Cua Cua is the owner of the picó powering the party I attended in Santa Marta. Despite being only thirty years old, he explained me how he had devoted half of his life to actively contributing to the culture. He started off as crew member of El Ultimo Hit, the oldest picó in Santa Marta, when he was only fifteen. Initially helping with lifting and maintaining boxes, as typically happens, his role progressed until he was in charge of the music selection. During his fifteen years of service with El Ultimo Hit, he fine-tuned his music taste and started to expand his own vinyl collection.

Loko Cua Cua selecting. Source: Instagram

In 2022 Loko Cua Cua decided to build his own machine, El Son Caribe. This is a traditional turbo, built by a Santa Marta-based box builder according to Loko’s own specifications. The pintura was made by a young artist also from Santa Marta. El Son Caribe is a four-ways system with six bass speakers allocated in the main box, some eight-inches midrange speakers and two types of high frequency drivers, all running off transistor amps. Loko considers himself as part of the recent ‘retro’ trend of picó culture in Santa Marta. However, he does not use the word retro, but rather ‘real’ or ‘traditional.’ He explained how he considered the huge fraccionados, mainly playing champeta urbana, with MCs chatting over the music, and a massive amount of electronic samples, getting ‘too far from the roots.’ Therefore, his idea was to build something that could keep the tradition alive. During the session, he played an inspiring mix of Caribbean and African music, some obligatory salsa, and a bit of cumbia.

El Son Caribe machine in Santa Marta. Source: Facebook

Loko had teamed up with Mono and another DJ friend to organize the dance I attended. The sound system was playing from a private court to avoid it being seized by the police. In fact, in Santa Marta it is prohibited for picós to play on the street. The court faced a nice, breezy square adorned by mango trees which helped to tame the tropical heat. I learned that dance was actually the first iteration of what they wanted to turn into a weekly event. Both Loko and Mono stressed how they aimed these regular events to bring picó culture ‘closer to the centre’, in a geographical as well as social sense, gathering friends and eventually a bigger crowd who wouldn’t necessarily go to a barrio dance. The location, that they described as a ‘neutral’ neighborhood, was particularly fit for the purpose; not in the tourist area (where they probably would have not been allowed to play); at walking distance from the city center, so not discouraging the younger crowd; and definitely not in any rough downtown barrio where some people won’t venture. There was no selling bar, but they kindly provided some beers and a grill, and there was a collection box for the DJs.

Even though the crowd was pretty small, the event well represented the effort of a new generation of sound system practitioners, selectors and DJs who are well-aware of the immense cultural value of the picó as well as its commercial potential, and who are keen to try and bridge different worlds through music and sound. The love for the music in its traditional format is the fuel that keeps them going despite the ongoing challenges, the stigmatization, and the financial constraints. We at SST cannot but wish them a longstanding success!

—

Brian D’Aquino is Senior Research Assistant in the SST project. He’s an author, sound system practitioner and music producer based in the Southern side of Europe.