Jamaican Sound System Professionals Reasoning Session

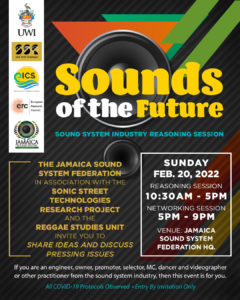

Poster for the event

Held in Kingston Jamaica on Sunday the 20th of February 2022, ‘Sounds of the Future’ has been a research event bringing together professionals from the sound system scene to discuss the current state of the industry in Jamaica. The one-day event was staged satellite to the 7th Global Reggae Conference and part of the Reggae Month calendar. ‘Sounds of the Future’ was dubbed as a ‘reasoning session’ to align itself with local Rastafarian culture, where the term ‘reasoning’ stands for a gathering of like-minded individuals, coming together to discuss a topic in a non-competitive fashion, to the benefit of all participants and the wider community.

The SST non-extractive approach to research is in fact consistent with the ‘reasoning’ spirit. The research purpose of the event was to support the local scene by consolidating the work of its representative bodies and facilitating discussion among practitioners for the advancement and wellbeing of the culture. The idea of nurturing conversations among sound system as well as other SST professionals has been very central to the SST project ethos from day one. In fact, it represents a step forward in the direction of a practice-based research methodology developed over several years by Sound System Outernational.

While SST envisioned and sponsored the event, it was realised and facilitated by the Jamaican Sound System Federation (JSSF). The event was held under their banner and their co-president and Federation chair Tony Meyers provided the venue for the day. Our SST research associates from the Centre of Caribbean Cultural Studies (CCCS) at UWI Mona, namely Dr. Sonjah Stanley Niaah and Dr. Dennis Howard chaired the discussions and together with Ashly Cork curated the staging of the event.

It must be pointed out that without these parties’ effort, and especially the trust they were granted by the local practitioner’s community, the event would have never been possible. While globally influential and widely renowned, sound system culture in Jamaica is still a very local grassroots phenomenon, usually regarded with suspicion by the middle class and the media and repressed – rather than regulated – by the government. It is a scene not easily accessible to outsiders for research purposes, and the successful outcome of the day was due to the solidity of pre-existing relations of mutual respect built over many years.

The SST research effort benefited hugely from the Federations’ trust and longstanding local knowledge and CCCS research expertise and experience. This approach fosters SST commitment to build local capacities for both local organisations and researchers. The discussion was captured on film for a documentary to be premiered JSSF HQ yard, Minott Terrace, Kingston, where it was staged.

Morning session kicking off

Politricks and Pushback

The JSSF HQ is also a renowned sound system workshop and home to Tony Myer’s Jam One sound system. The massive stacks of speaker boxes provided not only an evocative scenery but also some lively musical entertainment during the breaks. The invitation circulated by the JSSF was well-received and the list of confirmed participants appeared to be very promising, with founding figures of the Jamaican sound system scene as well as younger sounds and up-and –coming practitioners (see the full list of attendees at the bottom of the page). The research purpose was to provide a space where they could speak among themselves and we as researchers could listen.

Dr Stanley Niaah chaired the morning session entitled ’Politics and Pushback.’ This focused on the current state of the industry, including the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the ongoing relationship with the government and police forces, and considerations on the acknowledgement of sound systems as a legitimate productive force within the entertainment sector in Jamaica.

As Dr Stanley Niaah pointed out in her introductory remarks, “Jamaica is the only country that has given the world seven or eight distinct genres of music in the latter half of 20th century in a 50-year span.” Being the main engine behind this musical abundance, she advocated for the sound system to be regarded as “Jamaica’s national instrument,” just as the steel pan drum is celebrated in Trinidad.

Unfortunately, the reality has proved to be quite different. All speakers stressed how sound systems in Jamaica struggle to find official recognition by the government while they suffer from increasingly restrictive legislation. Lack of licensed venues, noise regulations, tight curfew times, and cost of permits were listed as some of the factors threatening the health of the industry during the last decade. The pandemic has not but exacerbated existing issues, with the entertainment sector still awaiting restrictions to be fully lifted. As Ronnie Jarrett from 8 Mile Sound pointed out: “It seem like the government people are anti-music. Because this was the first thing that they shut down as soon as the Covid thing kick in. Shut down in totality!”

The interdependence (and sometimes overlapping) between different professional profiles in the industry was also highlighted, with James Howard of Shang Hi Solophonic noticing how he was hit by the pandemic “three ways […] as a soundman, a venue owner, and promoter.” The usual lack of government support (rather neglect, if not a total pushback) has been worsened by the rise of corruption among the police forces, who added covid-related fines and charges to their disciplinary weaponry. As one speaker sadly put it: “As you talk about police, right now police are make money out of this dance thing more than we. I’m telling you!”

Another relevant point was the importance of the sound systems to the wellbeing of marginalised, poor communities. Here the presence of dancehall sessions on a regular basis was seen as not only providing affordable entertainment and small business opportunities to the unprivileged residents, but also contributing to tame the level of violence in the community. As JSSF co-president Anthony Meyers powerfully put it: “Where every time the event them stop keep, the crime get wickeder in a the community. Because when a man not have nothing fi do, you know, the crime can just get wickeder.”

Despite the hardships, all speakers expressed their loyalty to the culture in its undiluted form, with that obviously including a huge stack of speakers, but also playing to a local crowd of regular punters and supporters. As Jack Scorpio from Black Scorpio noted: “Sometimes is when we travel we earn, to be honest […] We earn a little extra, but we can’t give up Jamaica, to be honest.” This call to integrity also emerged in relation to the rise of streaming sessions during the lockdown. Despite seen as an opportunity to reach a wider audience, online sessions were not considered as a suitable alternative to a real dance, nor as a sustainable business model. As one speaker commented: “When I see people streaming online and all of that, that’s coming like somebody just cheated the game.”

While the lockdown has pushed a few sound owners to downsize or turn to powered boxes, the integrity of the sound system business was consistently seen as key for the wellbeing of the industry, together with the need to pass on the knowledge to young professionals through apprenticeship and intergenerational dialogue. This was another aspect in which the event seemed to be successful, as noted by Luke Davis-Elliot, son of Digi Tech, who stated : “My father owned a sound […] I always looked on that sound, I was like, I don’t know if I’m going back there because of how digital I am personally. Coming here, I realize that this is what I want to do … this is the real stuff.” It was great to hear from the youngers like Luke and DJ Tatiana from High Grade sound.

Hand-painted emergency exit signal

Technologies and Techniques

Dr Dennis Howard chaired the afternoon session entitled ‘Technologies and Techniques.’ This aimed to discuss ongoing shifts in technology, music, and aesthetics in the dancehall session as a way to unpack the ever-changing relation between technology and culture. The session kickstarted with a passionate debate around the definition of a ‘real’ sound system, where participants highlighted the convergence of distinct factors such as the need for a certain type of equipment, the knowledge of the music and the skills for presenting it, thus making clear the level of complexity which marks the sound system as a distinctive techno-cultural apparatus.

Overall, what came up was an “ongoing clash” between “the aesthetic and the heritage of sound system versus the practicality of nowadays technology,” as Dr Howard brilliantly put it. It was interesting to notice how the dispute was cutting across generations, with some of the elder professionals taking the side of one or the other view. The ‘tradition vs innovation’ dispute was also framed in the wider context of the global supply chain. Economy of scale, circulation of cheap Chinese components, and costly import duties were listed as some of the factors inhibiting a local manufacture chain to emerge. As a result, in recent years some of the most representative sound systems of Jamaica had their equipment built abroad and shipped in. This was seen by some as a pushback for the whole industry in terms of building the ‘Jamaican brand’ internationally. As one speaker said: “I don’t think anybody is going to get on a plane in Greece and fly to Jamaica to see some foreign boxes playing.”

The discussion on the quality of sound and its importance in the context of the dancehall session was another topical moment. All participants agreed on the need for clarity over power, with elders such as Jack Scorpio suggesting old school equipment to be a plus in that sense. Nonetheless, different school of thought emerged about the best techniques to employ in order to achieve that quality. Some participants stressed the importance of a good tuning process to be performed as part of the soundcheck, while others insisted that tuning had more to do with the actual building. As Ronnie Jarrett claimed, wearing his box builder’s hat: “The tuning is done when I put my tape measure on that piece of plyboard!”

The music aspect of the dancehall session was another relevant topic. The knowledge of the tunes, the ability to please and entertain the crowd and the potential for ‘feeling’ the music played were deemed as the fundamentals of a good selector, despite the changing trends. In this respect, the decline of sound clashes and dubplate specials – a crucial aspect of dancehall culture from its early days up until the 2000s – was also acknowledged. But that seemed to be widely accepted as being organic to an extremely lively culture, which has seen continuous waves of innovation during a relatively short period of time, turning Jamaica into one of the most prolific sonic laboratories of modern days. Instead, what some participants lamented is how internet-based platforms has undermined sound system’s authority within the local music industry, where they have traditionally exercised a sort of ‘quality control’ over the music produced – and this to the detriment of Jamaica’s musical landscape.

Filming the event

Aims and Ethics

As Stone Love founder Winston ‘Wee Pow’ Powell (also representing Bass Odissey for the occasion) argued during the event, “what an industry needs is two things to be named as such: aim and objective, and ethics.” What the day made clear is that the Jamaican sound system scene does not lack any of these. What could be beneficial to ensure that the culture continue to reproduce itself is to deepen the level of discussion and widen the floor: something to which we hope the open and always amicable discussion between the professionals at the event might have contributed.

From a research point of view, Sounds of the Future was in many ways a milestone in the SST project trajectory. In building the archive of the different SST scenes around the world the project’s ambition is not only to contribute to decolonize the relation between technology and culture, but also to make good use of our international academic status and financial resources to both document and try and contribute to the wellbeing and development of the local SST scenes. We would like for our forthcoming documentary film of the event to help strengthen the Federation and Jamaican sound system professionals’ requests for more support, recognition and respect for an industry that has left its mark on the popular music and culture across the world.

End of the session group picture

List of Speakers:

Anthony Meyers (Jam One and JSSF board member)

Clarence Cain (Kozmik Sound)

Errol Campbell and DJ Tatiana (High Grade Sound)

Hugh James (Jam Rock, formerly Redman Intl, and JSSF board member)

Maurice Johnson aka Jack Scorpio (Black Scorpio)

James Howard aka Jimmy Solo (Shang Hi Solo Phonics)

Joshua Chamberlain (JSSF board member)

Luke Davis Elliot (selector, son of Digitech Sound)

Monty Blake (Merritone)

O’Brien Rowe (OB Sound)

Ronnie Jarrett and Norman Williams (8 Mile sound)

Winston ‘Wee Pow’ Powell (Stone Love, also representing Bass Odyssey)

—

Brian D’Aquino is Senior Research Assistant in the SST project. Author, sound system practitioner and music producer, he is based in the Southern side of Europe.